During the American Revolution, people had to decide which side to support. Colonists for independence from England were usually called revolutionaries or whigs. But some Americans thought that to break away from the British government would not be right; they usually were called loyalists or tories. (Whig and tory were the names of rival political parties in Britain, so they were familiar nicknames in the colonies.) Americans today call the revolutionaries patriots, a word meaning “those who love their country.” Because we cherish our country’s independence, we value the revolutionaries as heroes.

Today it is easy for use to see why people wanted independence for the American colonies. We can even imagine ourselves joining in the fight against British rule. It is not so easy to understand why people who had lived in America for all or most of their lives would be opposed to the Revolution. Sometimes colonists were forced to make a choice for one side or the other, and they made choices they later regretted. Some people changed their minds and switched sides during the war, sometimes more than once.

There were many different reasons why colonists were revolutionaries or loyalists. Sometimes they chose sides according to what was happening in their own communities and what their personal needs were. If people they did not get along with did not want independence, they might take the revolutionary side. Likewise, if their local rivals were the ones who “talked up” independence, they might become known as loyalists simply because of their rivalry with the revolutionaries.

Some people tried to avoid taking sides. This usually did not work. About a year after the Declaration of Independence was signed, the North Carolina revolutionary government made laws requiring men of military age to take an oath of allegiance to the new state government and to serve in one of its military forces. Some exceptions were made for members of four Christian religious groups that were widely recognized as pacifists. These were the Quakers, Moravians, Mennonites, and Dunkers (also known as German Baptists). The state’s government allowed members of these four groups to avoid military service by paying taxes three or four times higher than the usual rate. But pacifists other than members of these four religious groups were not allowed to get out of military service.

Taking the Loyalist Side: Story of Connor Dowd

Perhaps one North Carolinian’s story can help us understand why some Americans took the loyalist rather than the revolutionary side. What is known of Connor Dowd’s life leads us to think that religious pacifism may have influenced his thinking. When the Revolution began, he may have decided that the war was wrong. It is also true that he did not get along with one of his neighbors, Philip Alston, who was an outspoken revolutionary. Here is Connor Dowd’s story.

Connor Dowd came to America from Ireland, long before the Revolution. While a boy in County Cavan, he learned from his family how to bleach the linen cloth that people wove in their homes and then sold to the “linen bleachers.” In 1754, his mother gave him some of her linen to start a business in America. He took it to North Carolina and used it to go into business as a peddler, as salesmen were called in those days.

Young Dowd worked hard and was soon employed by a Wilmington merchant. He sold his employer’s goods in the upper Cape Fear River valley and got to know the area and its people. He met and married a woman who owned five hundred acres and became wealthy by growing crops and raising livestock. After his wife died, he married a second time. His new wife, Mary, helped him in business by doing something he could not do -- she kept his business records because he could not read and write.

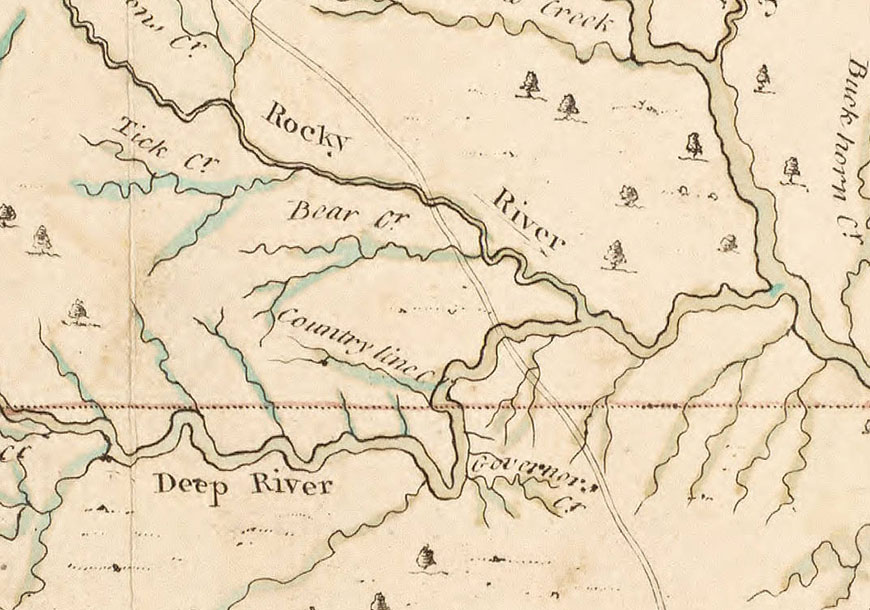

Dowd bought land from the colonial government and from other people. By 1776, he owned several thousand acres scattered through today’s Chatham, Moore, and Lee counties. His main operation was on the Deep River near present-day Carbonton.

I addition to his grain crops and animals, Dowd had peach and apple orchards, a tannery for making shoe leather from cowhide, and a distillery for making whiskey from grain. He used the fast-moving waters of Deep River to run four mills. There was a sawmill for cutting timber into lumber, a gristmill to grind grains into meal and flour, and a bolting mill for cleaning and sifting the flour. There was even a barkmill where oak bark was ground to extract its tannin used to make the cowhide into leather. Dowd enslaved eleven people, and one of them, a man named Israel, supervised the barkmill and the entire tanning operation.

Wagons hauled Dowd’s products from his farming and manufacturing center to the town of Cross Creek, today known as Fayetteville. Here his products were sold and the wagons were reloaded with goods from Cross Creek to sell in his stores. These goods included some items imported from Britain by the Wilmington merchant he used to work for. Dowd’s store on Deep River and his nearby ferry, tavern, gristmill, and tannery attracted many travelers, so “Connor Dowd’s place” became an important stop on the main road between Hillsborough and Cross Creek. For years after the Revolution, that section of the road was known as Connor Dowd Road.

Dowd's support for Loyalist forces at the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge

Dowd was involved in North Carolina’s first Revolutionary War battle at Moores Creek Bridge, but not directly in the fighting. In January 1776, Royal Governor Josiah Martin expected British troops to land soon on the coast. The Governor wanted the people to show their support for him and King George’s government so that the British would try harder to stop the Revolution. He sent out word to men he knew and trusted asking that they support him. He asked them to get others who opposed the revolutionaries and come to Brunswick (south of Wilmington on the Cape Fear River) in order to welcome the expected British landing.

Connor Dowd was not one of the men Martin asked to help raise his loyalist army. The Governor knew and liked Dowd. But the governor might have heard that Dowd did not believe in fighting and so did not ask for his help.

However, Dowd was against the revolutionaries. About five years before, during the Regulator disturbances, Dowd and his wife were members of the Haw River Separatist Baptist Church. This strongly pacifist congregation had forbidden its members to “take up arms against la[w]ful authority,” that is, the established government. Some members of the church had suffered at the hands of the Regulators as a result of this stand. So in 1775 and 1776, when the Revolution was taking hold, Dowd no doubt remembered his church’s position a few years earlier and believed that the revolutionaries were going against the “lawful authority” of king and Parliament. So his religious beliefs and the earlier experiences of his church may have influenced Connor Dowd to oppose the Revolution.

Dowd went out of his way to help the loyalist force that responded to Governor Martin’s call. He did not go as a fighting man, but he gave them supplies: bolts of wool and linen, shoes and shoe leather, wagons, flour, venison, iron, and one hundred pounds of pistol powder. And he went into debt to buy beef and pork. This debt was the main cause of his wife’s losing “Connor Dowd’s place” after the war to men who wanted to collect on Dowd’s debt note.

The loyalist force never reached Brunswick. They were surprised by revolutionaries at Moore’s Creek Bridge and were soundly defeated. After the revolutionaries’ victory, Dowd and many others were jailed. He was freed after paying a much higher bail than most of the other loyalists had to pay.

Many Loyalists went over to the revolutionary side

In the months and years after this battle, many loyalists in North Carolina gave in to revolutionary pressure and renounced their loyalty to the king. They took the required oath to the state and many even fought for independence. Some of them remained revolutionaries, even after British forces came to the state in 1781. Connor Dowd, however, never transferred his loyalty from the king to the state, but he came close to doing so.

Dowd seemed almost ready to go over to the revolutionaries in 1777. Robert Rowan, a revolutionary leader whom Dowd respected, tried in a friendly way to get Dowd to take the oath to the state. In a letter he wrote to Governor Richard Caswell, Rowan described what happened to his effort. The letter tips us off to some bad feeling between Dowd and revolutionary neighbor Philip Alston. Alston lived in the house which today is known as “The House in the Horseshoe,” about five miles from Dowd’s.

In his letter, Rowan had harsh things to say about Alston and two other revolutionaries in the neighborhood:

I am well convinced... from your love of liberty, that you will endeavour to put a stop to the evil conduct of our Militia officers and Justices... There was Conner Do[wd] taken prisoner, and brought down under guard by Mr. Alston. I was much surprised on enquiry to hear of his being charged with treasonable practices, against the State, as from a conversation I had with him some time before, [I] was persuaded he intended taking the oath.

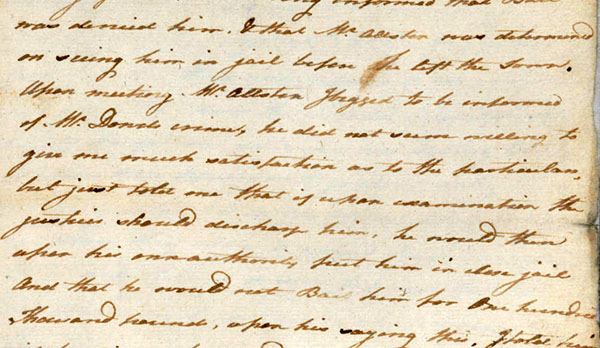

However knowing Mr. Alston’s position well, I was afraid there was perhaps some private pique or resentment in the case, or that [Dowd’s] crime must be very great indeed, being informed that bail was denied him, and that Mr. Alston was determined on seeing him in jail before he left the Town. On meeting Mr. Alston I begged to be informed of Mr. Do[wd]’s crime [but] he did not seem willing to give me much satisfaction to the particulars, but just told me that if upon examination the Justices should discharge [Dowd], [Alston] would then upon his own authority put him in close jail, and that he would not Bail him for one hundred thousand pounds. Upon his saying this, I told him, if he did so, he would behave like a Tyrant, which threw him into a violent passion, and on the trial at Wilmington, it plainly appeared that personal resentment and malice governed the conduct of Mr. Alston during the whole prosecution.

Rowan went on to accuse Alston of other actions that influenced many citizens against the revolutionaries:

The day of the General Muster he behaved still more like a Tyrant... One poor infirm man, seventy years of age, that many years had laid by the profits of a few potatoes, Turnips, Greens, &c was compelled to take [the state oath] or go to jail, another poor man, from one of the back counties had his loaded wagon carrying home salt to relieve his family, brought back a dozen miles and the owner thrown into jail for saying he would not take the oath here, but in his own County. In short, Sir, it would tire your patience were I to give you a full detail of the behaviour of our worthy Justices. Mr. Alston seems to rule them all, and a greater tyrant is not upon earth... and it is much to be lamented, that about two or three years ago, no Gentleman... would have kept this hectoring, domineering, person company.

Rowan concluded by saying that unjust revolutionaries were hurting the cause of the Revolution:

I can assure your Excellency, we have not the shadow of liberty among us. The great object we are contending for, at the expence of our blood, our ruling men have at present lost sight of.

Did Alston’s treatment of Dowd keep Dowd from supporting the Revolution? Rowan thought it did. Dowd’s story suggests another question, too. Before Alston arrested Dowd, and even before Dowd supplied the loyalists who answered the British governor’s call, did a local rivalry between Philip Alston and Connor Dowd influence one of them to become a revolutionary and the other to take a stand against the Revolution? Their circumstances suggest, but do not prove, that this was so.

Reprinted by permission from Tar Heel Junior Historian 32, no. 1 (Fall 1992): 7-12, copyright North Carolina Museum of History.