Calvin Henderson Wiley (1819-1887) was North Carolina's first superintendent of common (public) schools, serving from 1853 to 1865. He was born in the part of Guilford County which eventually became Alamance County. After graduating from the University of North Carolina in 1840, he taught, wrote novels, edited literary journals, and served in the North Carolina General Assembly before becoming state superintendent. He also wrote The North-Carolina Reader, a basic textbook that became standard in the state's schools in the 1850s.

Here he describes the setting of part of his novel Alamance, the Old-Field School, "a neat log-building, situated in the skirt of a thick wood, with a large, old field in front." Wiley presents the Old Field School as a typical local school of the late eighteenth century. Although his descriptions are part of a novel, they seem to be based on the author's memories of his own childhood.

Still, you should ask yourself whether anything Wiley describes sounds idealized — better than it probably really was — or exaggerated for effect. Have your parents or grandparents ever told you about how school was in "their day," to make a point about how things ought to be now? Does Wiley say anything that reminds you of those conversations?

Although boys and girls attended Wiley's fictional school together, it probably goes without saying that black and white children did not. When schools educated free people of color (as black Americans and American Indians who were not enslaved were called), they did so separately from white students. In 1808, for example, John Chavis of Raleigh advertised that he was opening "an evening school for the purpose of instructing Children of Colour, as he intends, for the accommodation of some of his Employers, to exclude all Children of Colour from his Day School." It seems that Mr. Chavis — possibly a Yankee — had made the mistake of admitting black students to his school and was quickly told by the parents of his white students that he would have to stop. (Raleigh Register, August 25, 1808.)

At Alamance the qualifications of the master"Master" in this context was short for schoolmaster, or the teacher. were tested by an examination by the parsona minister or preacher and others best qualified to judge; and it is to be observed, that the fact of being a leading politician, or of holding a commission to be a justice of the peace, no more made a man a scholar than did the possession of land and negroes render him a gentleman. Once installed into office, the master was subject to the control of no impertinent intermeddlers, and, being absolute monarch in his little kingdom, he governed it according to his own conscience and discretion, and without favour or partiality. The teacher out of school was the equal, the companion, and Mentor of his pupils; and hence, between him and them there was not that awful and impassable gulf which now separates professor and student, and renders them the implacable and hereditary enemies of each other. The master, to diffuse the benefits of his conversation, and to prevent imputations of undue favour to any, was the guest of all his patrons, with each of whom he boarded and lodged by turns, and in the families of all of whom he was an honoured memberUntil the twentieth century, it was common for a teacher to live with the families whose children attended his school. As a result, teachers were most often single men without families or homes of their own.. It was considered important that he should have at least a moderate share of common sense; he was believed to be subject to human sympathies and mortal feelings, and hence, out of school was regarded as a man and a Christian, and in all neighbourhood affairs had "a voice potential."...

Hector M'Bride having been chosen as the teacher, many vague rumours about him got into circulation among the children -- some representing him as very mild, and others as extremely expert at the use of the birch Birch twigs were used to whip the hand of a child who had missed behaved. Teachers were allowed to use corporeal punishments on their students.. His merits were talked over and discussed at length, and no satisfactory conclusion having been arrived at, all determined to wait till they had tried him. On the day of commencementThe first day of school (the day on which school commences, or begins).... he made an address, laying down the principles on which he should conduct the school, and thereupon read a long list of rules, commenting on and explaining each one separately. They were divided into three heads, and concerned the morals, the manners, and the studies of his students. As these rules are still preserved among the master's papers, and may prove interesting to pedagogues, a few of them are here given, with the number of each prefixed:

- The punishments shall consist of whipping, slapping in the hand with the rule, riding the ass"Riding the ass" is explained later in the document., and expulsion, according to the gravity of the offence.

- All the boys and girls may laugh, without noise, when any one is mounted on the ass; but no one shall speak to him, or make gestures or ugly mouths at him, in token of derision.

- When the master tells an anecdote the students are not bound to laugh immoderately, though it will be considered respectful to give some indication of their being pleased or amused.

- Whenever one enters or leaves the house, if a boy he shall bow, and if a girl courtesy, to the master, and when a stranger comes in all shall rise and do the same towards him.

- When the boys meet a stranger on the road they must take off their hats and bow: they are enjoinedrequired or ordered to be, on all occasions, respectful and attentive to their seniors, and not to talk in their presence, except when bidden.

- Every boy shall consult the comfort and convenience of the girls before his own, and whoever is caught standing between a female and the fire shall be whipped.

- If any boy is caught laughing at the homeliness of a girl, or calling her ugly names, he shall ride on the ass.

- Giggles are detestable, and when a girl is amused she must smile gracefully, or laugh out; and if the master catches any one snickering he will imitate and reprimand her in presence of the whole school.

- Every offender, when called on, must fully inform on himself, remembering, that by telling the truth he palliates his offence.

- When the master's rule falls at the feet of any one, he and all his guilty associates must come with it to the teacher.

- The master will inflict on every common informer the punishment due to the offence If you report on a fellow student for misbehaving, you'll receive the same punishment as the person who broke the rule. of which he maliciously gives information.

- As it is God who gives the mind, and as he has bestowed more on some than on others, it shall be considered a grave offence to laugh at or ridicule any one who is by nature dull or stupid, such persons being entitled to general commiseration rather than contempt.

- The girls must remember that the exemptions to which their sex entitles them are to be used as a shield, and not as a sword; and they are therefore enjoined to eschew the abominable and unlady-like habit of indulging in sarcasms and attempted wit at the expense of the boys. Whenever a girl loses the docilitysubmissiveness or a willingness to take instruction., gentleness, and benignity of manners becoming her sex, she forfeits her title to the forbearance and defferential courtesy of the males.

- No one shall, out of school, speak disrespectfully of the master, or of a fellow-student.

- No one shall ridicule, laugh at, or make remarks about the dress of another; the boys are enjoined to be kind and courteous to the girls, the girls to be neat and cleanly in their dresses, and all to act as if they were brothers and sisters, the children of the same parentsIn other words, no sexual behavior such as kissing or holding hands would be permitted..

- Let the words of The Preacher be held in constant remembrance, "Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth," &c., &c.

Such are a few of the many rules which the master declared he would read publicly once a month, and each one of which he said he would rigidly enforce, remarking that it was better to have no laws than good ones not strictly obeyed.

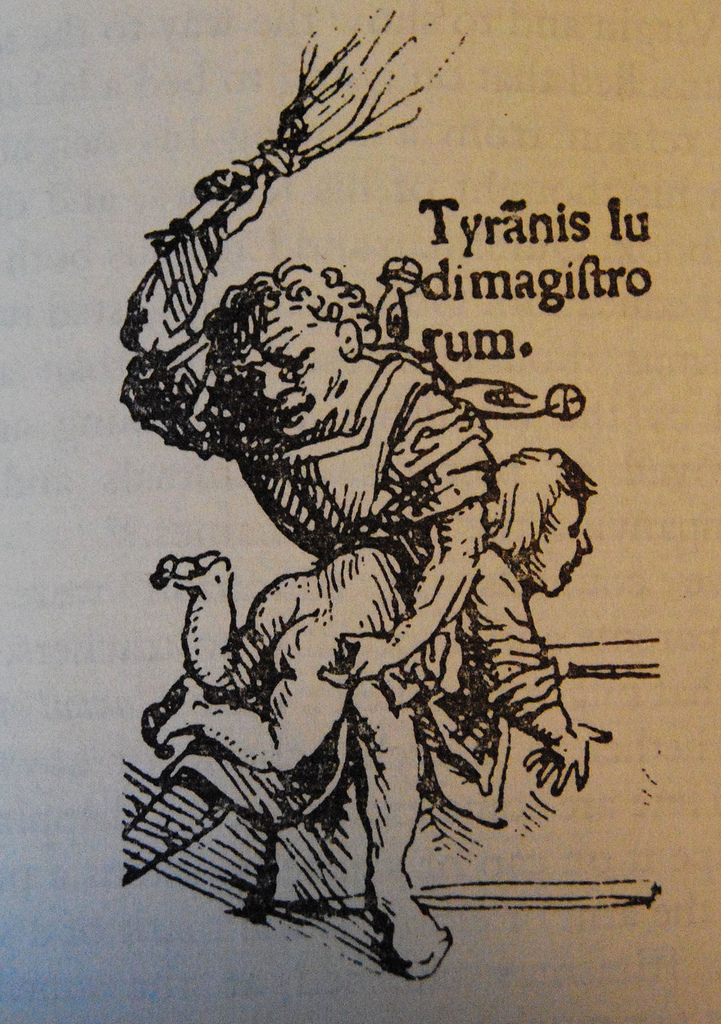

The punishment of riding on the ass was generally inflicted for long-continued and gross neglect of study, vulgarity of manners, and insults to the girls, and was as follows: -- The culprit, with a large pair of leather spectacles on his nose and a paper cap on his head, with the inscription "Fool's Cap," in Roman letters, was mounted astraddle one of the joists, being assisted up by a few cuts of the master's switch, which sometimes played, at intervals, across his legs during the hour that he held his seat. This punishment was only inflicted on the males, and was considered as so disgraceful that it was rarely merited, and when imposed attached a stigma to the culprit, which affected his standing in and out of school, for a long time afterwards.

Having thus got his school under way, the master, to inspire at once an affection for him as a man, as well as respect as a teacher, dismissed his students for recreation, went with them to the old field, helped to lay off the play-ground, and discussed with them the various kinds of sports, teaching them, by explanations and practical illustrations, many new ones, which were considered highly interesting. Thus in the morning he at once established for himself a high character as a scholar and disciplinarian; by noon he was the fast friend of every scholar he had, and that evening boys and girls went home perfectly delighted with their new teacher, and feeling an emulous desire to excel in their studies which they had never felt before. In a word, the master was, in each scholar's eye, the very perfection of a man, and to be like him was the highest ambition of all.