One of the most cherished and widely retold stories in recent North Carolina history is the tale of the Blue Ridge Parkway's "missing link" at Grandfather Mountain. This approximately seven-mile section of the road remained uncompleted for two decades after the rest of the Parkway was finished in the late 1960s. It finally opened in 1987, fifty-two years after Parkway construction began in the midst of the Great Depression.

At the heart of the popular story is the tale of the how Grandfather Mountain owner Hugh Morton "saved" what is usually described as an ecologically fragile yet pristine and undeveloped mountain from the National Park Service's supposed plans to route the Blue Ridge Parkway "over the top" of the beloved peak in the 1950s and 1960s. Countless publications have portrayed Morton as a lifelong conservationist who single-handedly halted what is characterized as an environmentally irresponsible Park Service plan to take -- in Morton's oft-repeated phrase -- a "switchblade to the Mona Lisa."

In the end, Morton forced the Park Service to adopt a lower route. The construction of the iconic Linn Cove Viaduct -- an engineering marvel that greatly reduced construction damage along a quarter-mile part of the route that traversed an unstable boulder field -- provides a neat end to this simple, but misleading account.

The historical record of the battle between Morton, North Carolina's State Highway Commission (responsible for Parkway land acquisition in the state), and the National Park Service (NPS) over the Parkway route reveals a much more complicated drama. Key parts of this story that have dropped out of view over the years reemerge vividly from Hugh Morton's own photographic record, heretofore largely unseen.

An enthusiastic and talented nature photographer, Morton took hundreds of photographs of and along the Blue Ridge Parkway. His most recognizable Parkway images -- featured in many a magazine, state travel guide, poster, and billboard -- highlight its scenic beauty: a car meandering through Doughton Park, stunning fall colors, a carefully-placed pink rhododendron hovering over the endlessly photographed Viaduct. Similarly, large numbers of his photographs of Grandfather Mountain feature wildlife, waterfalls, flowers, and close or distant natural vistas.

But digitization of the Morton collection permits photographs less artistic but more relevant to documenting the history of the Parkway at Grandfather finally to be widely available.

Most important are the photographs of Morton's development of a promising tourist site at Grandfather in the early 1950s. Like many other private tourism entrepreneurs in the North Carolina and Virginia mountains, Morton hoped the Blue Ridge Parkway would funnel travelers to his gates.

Throughout the 1950s, however, he battled the Park Service over what he perceived (sometimes rightly) as its insufficient attention to promoting and helping regional business interests. He led opposition to Park Service policies prohibiting advertising signs on the Parkway and fought several proposals to impose park entrance fees. And he resisted a planned expansion of government-operated visitor facilities under the NPS's Mission 66 construction program (1956-1966). Taking place in this context, his crusade against the Parkway "high route" was deeply intertwined with his development as a businessman and entrepreneur. And building his business at Grandfather, at least initially, induced Morton to flip open his own switchblade.

The story begins in the 1930s, when the state of North Carolina actually paid Morton's grandfather Hugh MacRae's Linville Company for a right-of-way for the Parkway along what is now Highway 221. By the 1940s, however, the Park Service and state engineers had concluded that the twisting and torturous Highway 221 could not be adapted to Parkway standards. With some cooperation from the MacRae family, they launched an ultimately unsuccessful effort -- spearheaded by longtime parks advocate and MacRae family friend Harlan Page Kelsey -- to purchase all of Grandfather for the Parkway. That effort ran aground in the late 1940s when Morton returned from service in World War II, took the helm of the company, and declared the mountain no longer for sale. Park Service and North Carolina highway officials then plotted another route for the Parkway (known during the controversy as the "high route") that lay about 600 feet up the mountain from 221 and included a 1700-foot tunnel through Pilot Ridge.

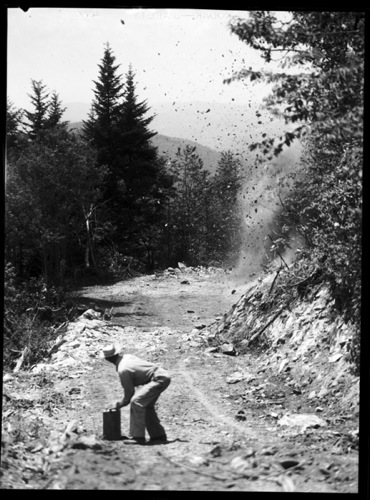

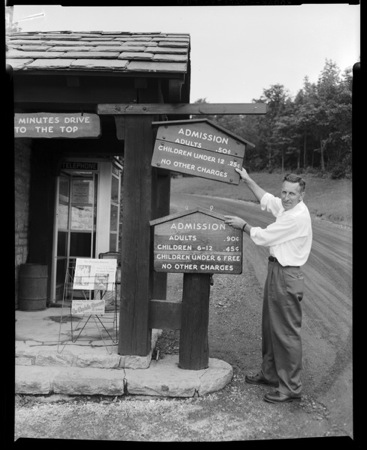

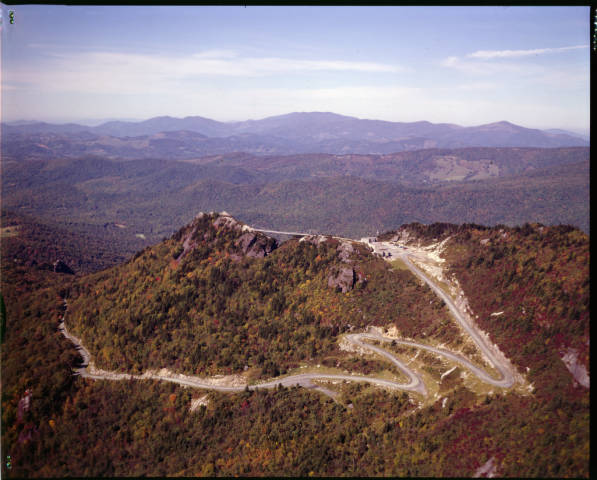

Meanwhile, bent on harvesting what he termed "rich crops of tourists," Morton in 1952 blasted a road to one of the mountain's summits, where he launched a wave of development that began with the "Mile-High Swinging Bridge," a new parking area and a small gift shop later that year. To recover his costs, he hiked the price of admission to Grandfather's peak from $.50 for car and driver ($.25 for additional passengers) to $.90 apiece for adults. In 1961, Morton built a much larger "Top Shop" to replace the modest early structure he had initially built at the summit parking area.

In the midst of this bustle of activity, the state acquired the new "high route" right-of-way by eminent domain in 1955. Morton protested loudly to Governor Luther Hodges (for whose 1956 gubernatorial campaign he managed publicity), and the Highway Commission was forced to deed the land back to him in 1957.

For the next thirteen years, stalemate reigned, as Morton -- supported by governors (and personal friends) Hodges, Terry Sanford, and Dan K. Moore -- stood firmly against the "high route." The Park Service, for its part, threatened simply to leave the Parkway unfinished rather than move the road lower on Grandfather. Ultimately, mobilizing his close connections with those in power in state government, Morton triumphed. Facing staunch state refusal to acquire land for the "high route," the Park Service agreed to what Morton termed a "compromise" route between the "high route" and 221. Construction began along this line in 1968.

While subsequent retellings have implied or stated that the conflict turned on the potential environmental impact of the Parkway's going "over the top" of Grandfather, an examination of the extensive documentary record from the 1950s and 1960s, which I conducted for my 2006 book, Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History, reveals first of all that the "high route" did not go "the top" of Grandfather, but lay several hundred feet below any of its summits. The documents also make a convincing case that the key issues had to do with the Parkway's expected effects on Morton's newly-hatched tourism enterprise, where visitation had ballooned from about 12,000 in 1946 to about 200,000 a decade later. Environmental protection in the way we now understand it -- or in the way Morton himself later came to see it -- played almost no role in the controversy.

Perusing the images from the Morton collection, one can appreciate the dramatic physical transformation brought to Grandfather's summit by the development of "Carolina's Top Scenic Attraction." That attraction, its Park Service critics pointed out, had caused considerable damage to the mountain at an elevation higher than the planned Parkway "high route." And despite employing some language decrying the "great scar" the Parkway would cause, Morton in the 1950s and 1960s worried most that the high route would, as he noted in correspondence, "interfere with our attraction" and "kill the development."

Supporters of the "high route" (including the Parkway superintendent, Sam Weems, and the head of Parkway land acquisition at the North Carolina State Highway Commission, engineer R. Getty Browning) fumed that by not acknowledging the scars his own development had already caused, Morton was misrepresenting the situation at Grandfather.

Road to the summit of Grandfather Mountain.

Most significant in their view was the 1952 construction of Morton's summit toll road and parking lot, photographs of which have until now been surprisingly elusive. In the summer of 1955, staff at the Parkway headquarters, scrambling to rebut Morton's resistance to land acquisition, desperately searched for them. "Do you have any pictures," a Parkway staffer asked Superintendent Sam Weems, "of the Swinging Bridge and environs showing how that has messed up the mt.?"

Morton, of course, had pictures. And those pictures, now available, remind us that the construction, which Morton himself described in a 1957 pamphlet as having entailed "blasting all the way" was far from gentle on the old Grandfather. Pictures show that "Top Shop" involved significant scarring and destructive modifications to the terrain and vegetation at the peak.

Morton's own images, at last, provide visual evidence of Parkway supporters' claims. They show Grandfather's peak "Hill Climb" car race, of a large new sign erected about 1959 at Linville to advertise the attraction, of merchandise in the bigger 1960s "Top Shop," and 1970s traffic congestion at the top of the mountain.

Navigating the relationship between the park and regional tourism interests has always been a central dilemma of Parkway management. The history of the Parkway at Grandfather is a reminder that, despite its "noncommercial" nature, the Parkway's history has always been intertwined with the aspirations and ambitions of travel and tourism business interests in the southern Appalachian Mountains.