From An Outline of US History

By the Bureau of International Information Program, US Department of State

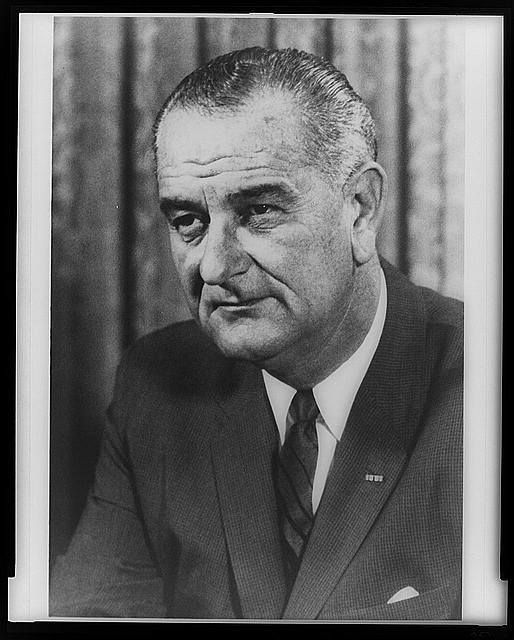

Lyndon Johnson, a Texan who was majority leader in the Senate before becoming Kennedy's vice president, was a masterful politician. He had been schooled in Congress, where he developed an extraordinary ability to get things done. He excelled at pleading, cajoling, or threatening as necessary to achieve his ends. His liberal idealism was probably deeper than Kennedy's. As president, he wanted to use his power aggressively to eliminate poverty and spread the benefits of prosperity to all.

Johnson took office determined to secure the passage of Kennedy's legislative agenda. His immediate priorities were his predecessor's bills to reduce taxes and guarantee civil rights. Using his skills of persuasion and calling on the legislators' respect for the slain president, Johnson succeeded in gaining passage of both during his first year in office. The tax cuts stimulated the economy. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the most far-reaching such legislation since Reconstruction.

Johnson addressed other issues as well. By the spring of 1964, he had begun to use the name "Great Society" to describe his socio-economic program. That summer he secured passage of a federal jobs program for impoverished young people. It was the first step in what he called the "War on Poverty." In the presidential election that November, he won a landslide victory over conservative Republican Barry Goldwater. Significantly, the 1964 election gave liberal Democrats firm control of Congress for the first time since 1938. This would enable them to pass legislation over the combined opposition of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats.

The War on Poverty became the centerpiece of the administration's Great Society program. The Office of Economic Opportunity, established in 1964, provided training for the poor and established various community-action agencies, guided by an ethic of "participatory democracy" that aimed to give the poor themselves a voice in housing, health, and education programs.

Medical care came next. Under Johnson's leadership, Congress enacted Medicare, a health insurance program for the elderly, and Medicaid, a program providing health-care assistance for the poor.

Johnson succeeded in the effort to provide more federal aid for elementary and secondary schooling, traditionally a state and local function. The measure that was enacted gave money to the states based on the number of their children from low-income families. Funds could be used to assist public- and private-school children alike.

Convinced the United States confronted an "urban crisis" characterized by declining inner cities, the Great Society architects devised a new housing act that provided rent supplements for the poor and established a Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Other legislation had an impact on many aspects of American life. Federal assistance went to artists and scholars to encourage their work. In September 1966, Johnson signed into law two transportation bills. The first provided funds to state and local governments for developing safety programs, while the other set up federal safety standards for cars and tires. The latter program reflected the efforts of a crusading young radical, Ralph Nader. In his 1965 book, Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile, Nader argued that automobile manufacturers were sacrificing safety features for style, and charged that faulty engineering contributed to highway fatalities.

In 1965, Congress abolished the discriminatory 1924 national-origin immigration quotas. This triggered a new wave of immigration, much of it from South and East Asia and Latin America.

The Great Society was the largest burst of legislative activity since the New Deal. But support weakened as early as 1966. Some of Johnson's programs did not live up to expectations; many went underfunded. The urban crisis seemed, if anything, to worsen. Still, whether because of the Great Society spending or because of a strong economic upsurge, poverty did decline at least marginally during the Johnson administration.