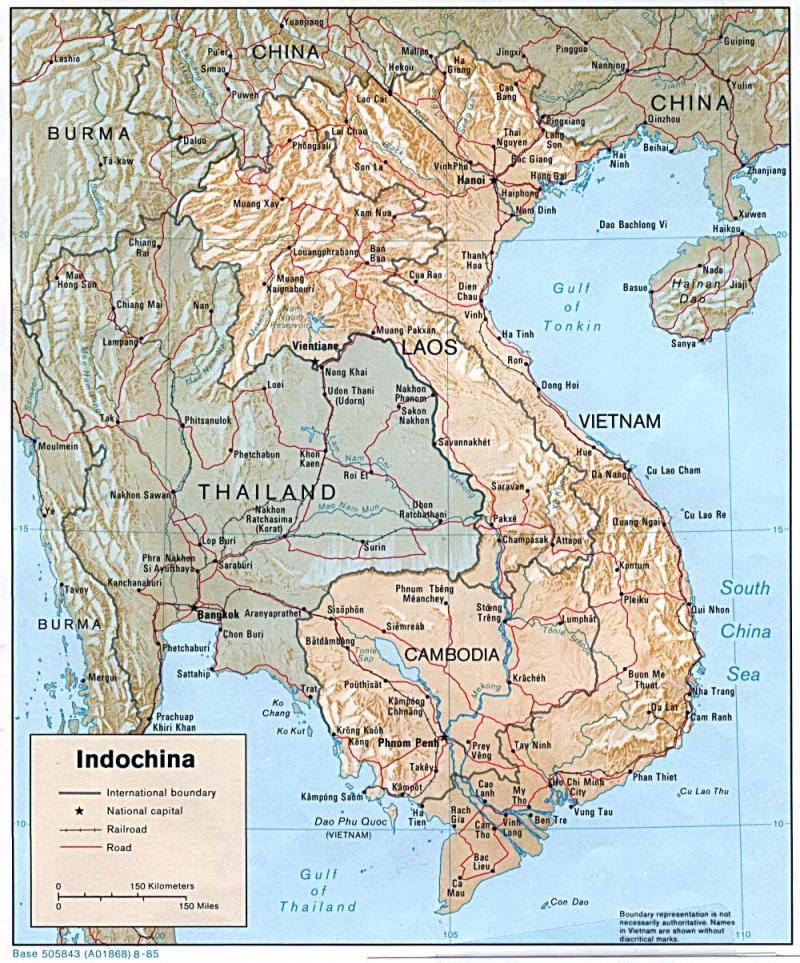

Indochina -- present-day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia -- was a French possession before World War II. Japan invaded Indochina in 1940, and after the war, the French effort to reassert colonial control was opposed by Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese Communist, whose Viet Minh movement engaged in a guerrilla war with the French army. Indochina soon became a Cold War battlefield.

The United States becomes involved

Both Truman and Eisenhower, eager to maintain French support for the policy of containment in Europe, provided France with economic aid that freed resources for the struggle in Vietnam. But the French suffered a decisive defeat in Dien Bien Phu in May 1954. At an international conference in Geneva, Laos and Cambodia were given their independence. Vietnam was divided, with Ho in power in the North and Ngo Dinh Diem, a Roman Catholic anti-Communist in a largely Buddhist population, heading the government in the South. Elections were to be held two years later to unify the country. Persuaded that the fall of Vietnam could lead to the fall of Burma, Thailand, and Indonesia, Eisenhower backed Diem's refusal to hold elections in 1956 and effectively established South Vietnam as an American client state -- a nation that was officially independent but effectively under U.S. control.Kennedy increased assistance, and sent small numbers of military advisors, but a new guerrilla struggle between North and South continued. Diem's unpopularity grew and the military situation worsened. In late 1963, Kennedy secretly assented to a coup d'etat. In the coup, Diem and his powerful brother-in-law, Ngo Dien Nu, were killed.

War in Vietnam

A series of South Vietnamese strong men proved little more successful than Diem in mobilizing their country. The Viet Cong, insurgents supplied and coordinated from North Vietnam, gained ground in the countryside.

Determined to halt Communist advances in South Vietnam, Johnson made the Vietnam War his own. After a North Vietnamese naval attack on two American destroyers, Johnson won from Congress on August 7, 1964, passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which allowed the president to "take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression." After his re-election in November 1964, he embarked on a policy of escalation. From 25,000 troops at the start of 1965, the number of soldiers - both volunteers and draftees - rose to 500,000 by 1968. A bombing campaign wrought havoc in both North and South Vietnam.Grisly television coverage with a critical edge dampened support for the war. Some Americans thought it immoral; others watched in dismay as the massive military campaign seemed to be ineffective. Large protests, especially among the young, and a mounting general public dissatisfaction pressured Johnson to begin negotiating for peace.

The election of 1968

By 1968 the country was in turmoil over both the Vietnam War and civil disorder, expressed in urban riots that reflected African-American anger. On March 31, 1968, the president renounced any intention of seeking another term. Just a week later, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis, Tennessee. John Kennedy's younger brother, Robert, made an emotional anti-war campaign for the Democratic nomination, only to be assassinated in June.

At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, protesters fought street battles with police. A divided Democratic Party nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey, once the hero of the liberals but now seen as a Johnson loyalist. White opposition to the civil rights measures of the 1960s galvanized the third-party candidacy of Alabama Governor George Wallace, a Democrat who captured his home state, Mississippi, and Arkansas, Louisiana, and Georgia, states typically carried in that era by the Democratic nominee. Republican Richard Nixon, who ran on a plan to extricate the United States from the war and to increase "law and order" at home, scored a narrow victory.

Nixon and Vietnam

Determined to achieve "peace with honor," Nixon slowly withdrew American troops while redoubling efforts to equip the South Vietnamese army to carry on the fight. He also ordered strong American offensive actions. The most important of these was an invasion of Cambodia in 1970 to cut off North Vietnamese supply lines to South Vietnam. This led to another round of protests and demonstrations. Students in many universities took to the streets. At Kent State in Ohio, the national guard troops who had been called in to restore order panicked and killed four students.By the fall of 1972, however, troop strength in Vietnam was below 50,000 and the military draft, which had caused so much campus discontent, was all but dead. A cease-fire, negotiated for the United States by Nixon's national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, was signed in 1973. Although American troops departed, the war lingered on into the spring of 1975, when Congress cut off assistance to South Vietnam and North Vietnam consolidated its control over the entire country.The war left Vietnam devastated, with millions maimed or killed. It also left the United States traumatized. The nation had spent over $150,000-million in a losing effort that cost more than 58,000 American lives. Americans were no longer united by a widely held Cold War consensus, and became wary of further foreign entanglements.