In the early dawn of April 12, 1861, a mortar shell fired from Fort Johnson in Charleston Harbor burst over Fort Sumter, inaugurating the American Civil War. For 34 hours Confederate forces bombarded the fort, forcing the Federal garrison to surrender. On April 14 victorious Southern troops claimed their prize.

For the next four years Fort Sumter remained a Confederate stronghold despite frequent Union attempts to capture it. Between 1863 and 1865, determined Confederate soldiers kept Federal land and naval forces at bay for 587 days -- one of the longest sieges in modern warfare. By February 17, 1865, the fort was virtually demolished and the Civil War was nearly at an end. The Confederates reluctantly abandoned the fort, leaving it to be re-claimed by Federal troops.

Coastal defense

The British attack on Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812 humiliated the United States. Both the Capitol and the White House were burned by the invaders, convincing President Madison and Congress to strengthen America's coastal defenses to prevent such incidents from happening again.

A plea from President James Madison led to a government survey of fortifications along the U.S. coastline. The report, completed in 1826, recommended the building of a new fort on a shoal in Charleston Harbor. The new fort would embody "structural durability, a high concentration of armament, and enormous overall fire power." With the guns of the proposed fort crossing fire with those of Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island, the important commercial seaport of Charleston could be effectively protected against attack.

The new fort in Charleston Harbor was named in honor of Thomas Sumter, brigadier general commanding South Carolina militia during the Revolutionary War. As the state's distinguished partisan leader, he became known respectfully as "The Gamecock of the Revolution."

Construction of Fort Sumter was slow and difficult, delayed by periods of insufficient funds and a sandbar that required thousands of tons of granite before work on the superstructure could begin. During the mid-1840s, workmen began laying 7,000,000 bricks for the 5-foot-thick outer walls that would tower 50 feet above low water level. By 1860, on the eve of the American Civil War, the fort was only 90 percent complete.

Fort Sumter on the eve of war

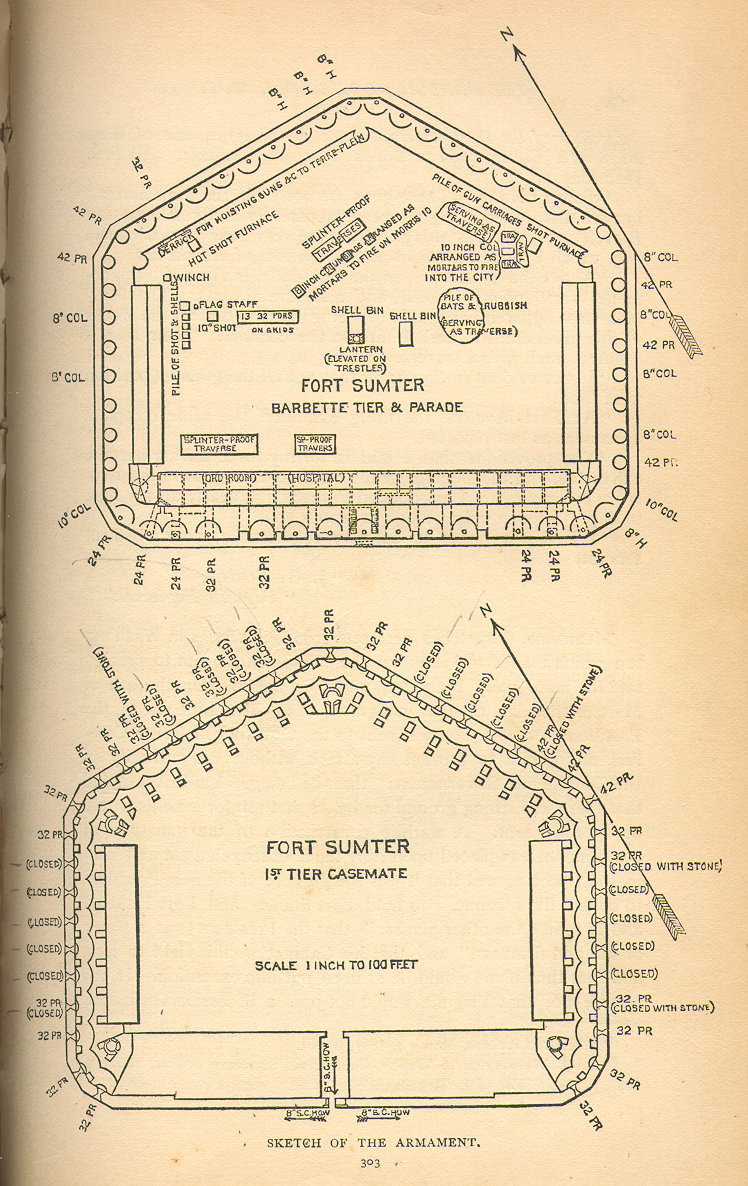

Fort Sumter covered 2.4 acres. Cannon from its 5 sides gave wide command of the harbor. The 4 shorter walls contained 2 tiers of arched gunrooms. More guns occupied the top level. The fort had 8 powder magazinesMagazines in this context means a storage room for arms and ammunition., 2 on each level at both ends of the long wall.

Fort Sumter was built for 135 guns and a garrison of 650 men. When the Federal garrison occupied Fort Sumter on December 26, 1860, though, neither of the enlisted men's barracks were complete. The officers' quarters, also incomplete, were observed nonetheless to have been made "for every comfort and convenience of the occupants usual in the best modern city dwelling." In addition to housing officers and their families, the officers' quarters also included ordnance storerooms and a hospital.

Of the 135 cannon planned for the gunrooms and atop the fort, though, only 15 had been mounted by late 1860. When Civil War erupted on April 12 the following year, 60 guns had been mounted by the garrison.

South Carolina secedes

South Carolina's secession on December 20, 1860, caused a crisis. Federal troops manned forts here, angering many Carolinians who believed that state should control its own military installations. At Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island, Major Robert Anderson commanded a post to protect the U.S. Government's interests.

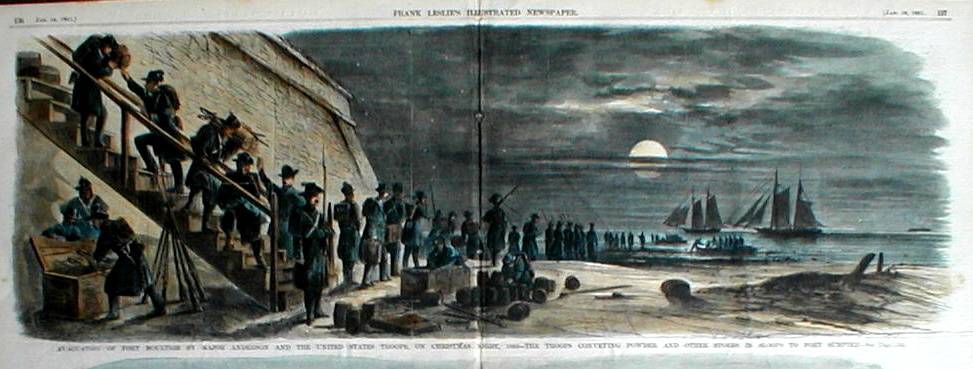

Six days after South Carolina seceded, Anderson transferred his command to Fort Sumter. The new masonry fort at the entrance to Charleston Harbor was more defensible than the older Fort Moultrie. More importantly, whoever controlled Sumter controlled access to Charleston - the South's most important seaport. Under cover of darkness, Major Anderson and his troops slipped out of Fort Moultrie and crossed the harbor to Fort Sumter. Several schooners carrying food, munitions, medical supplies, and 45 army wives and children followed the soldiers. Heavy smoke drifted ominously over Fort Moultrie. Before abandoning the fort, Federal troops had spiked the cannon and set fire to the gun carriages to prevent the Confederates from using the ordnance.

Charlestonians viewed Anderson's move as an act of aggression. In retaliation for taking of Fort Sumter, South Carolina troops were ordered by the governor to take Castle Pinckney - one of several Federal forts in and around Charleston Harbor. On December 27, 1860, the militia secured Castle Pinckney, allowing the Union occupants to leave without bloodshed. Additional state troops seized Fort Moultrie.

Federal troops under siege

When Federal forces occupied Fort Sumter in December of 1860, they had enough provisions to last four months. In January, a Federal relief ship left New York with supplies for the fort. When the Star of the West appeared at the entrance to Charleston Harbor, Citadel cadets opened fire. The unarmed ship turned back without reaching Fort Sumter.

The presence of women and children in Fort Sumter presented a serious problem. Their lives would be endangered if the fort was fired upon, and there was a dwindling food supply. Major Anderson made the decision to send them to New York to safety. They were taken first to Charleston and then boarded a steamer for New York. As they passed Fort Sumter on February 3, 1861, the troops "displayed much feeling; for they thought… they might not meet them again for a long period, if ever."

On March 3, 1861, Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard of Louisiana took command of the military activities at Charleston for the newly established Confederate States of America. Ironically, Major Anderson had been Beauregard's artillery instructor at West Point. Teacher and student were now on opposing sides of an impending war.

General Beauregard realized that the South Carolinians were eager, but they were amateurs at war. He set about organizing the Palmetto State's forces and implementing a plan to make Fort Sumter the center of a "ring of fire." As Beauregard energized the South Carolina troops and aimed artillery at Fort Sumter, Federal officers at Fort Sumter anxiously watched through spyglasses. By early April of 1861, the Southern fortifications bearing on Sumter were considerable. Fort Sumter had become a powder keg ready to explode. Who would fire the first shot?

The Confederates fire on Sumter

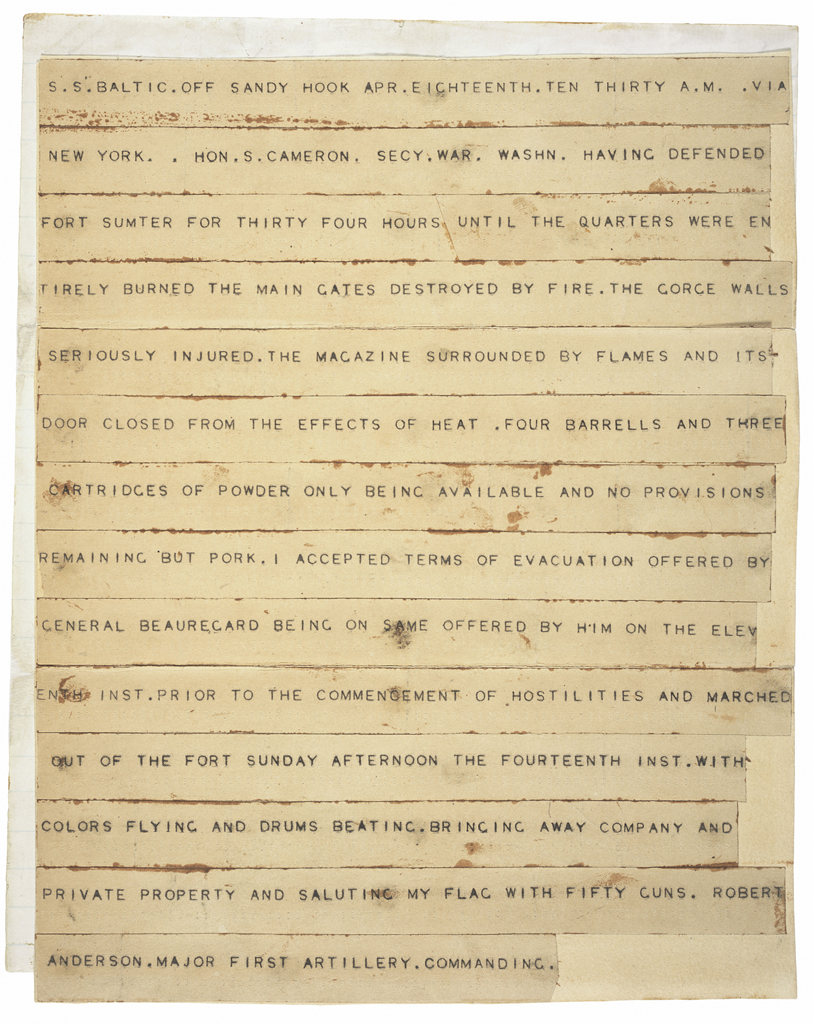

To avoid war, the confederate Government ordered General P.G.T. Beauregard to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter and if refused, to "reduce it." His aides visited the fort on April 11 under a flag of truce and presented Anderson with the ultimatum, but without success. After midnight, Beauregard's aides confronted Anderson again and received the same negative reply.

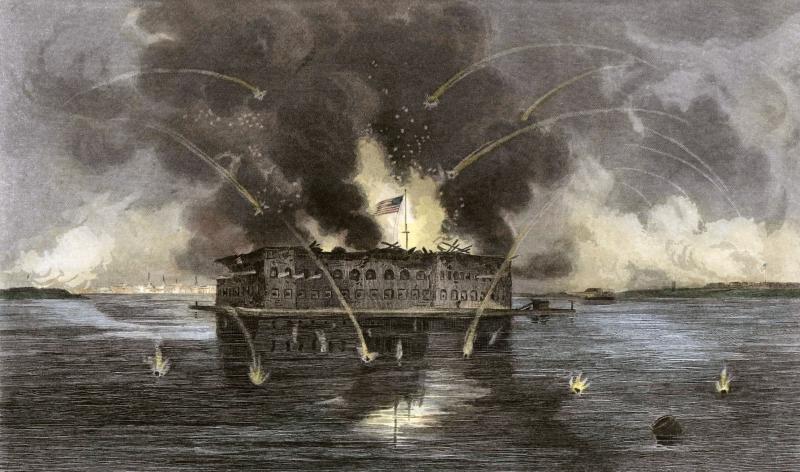

At 4:30 a.m. on April 12, Confederate Captain George S. James was ordered to fire the first shot of the Civil War. Fired from Fort Johnson on James Island, this historic shell burst over Fort Sumter and signaled the confederate batteries in Charleston Harbor to commence an assault on the fort. At daybreak, Union forces opened fire in response.

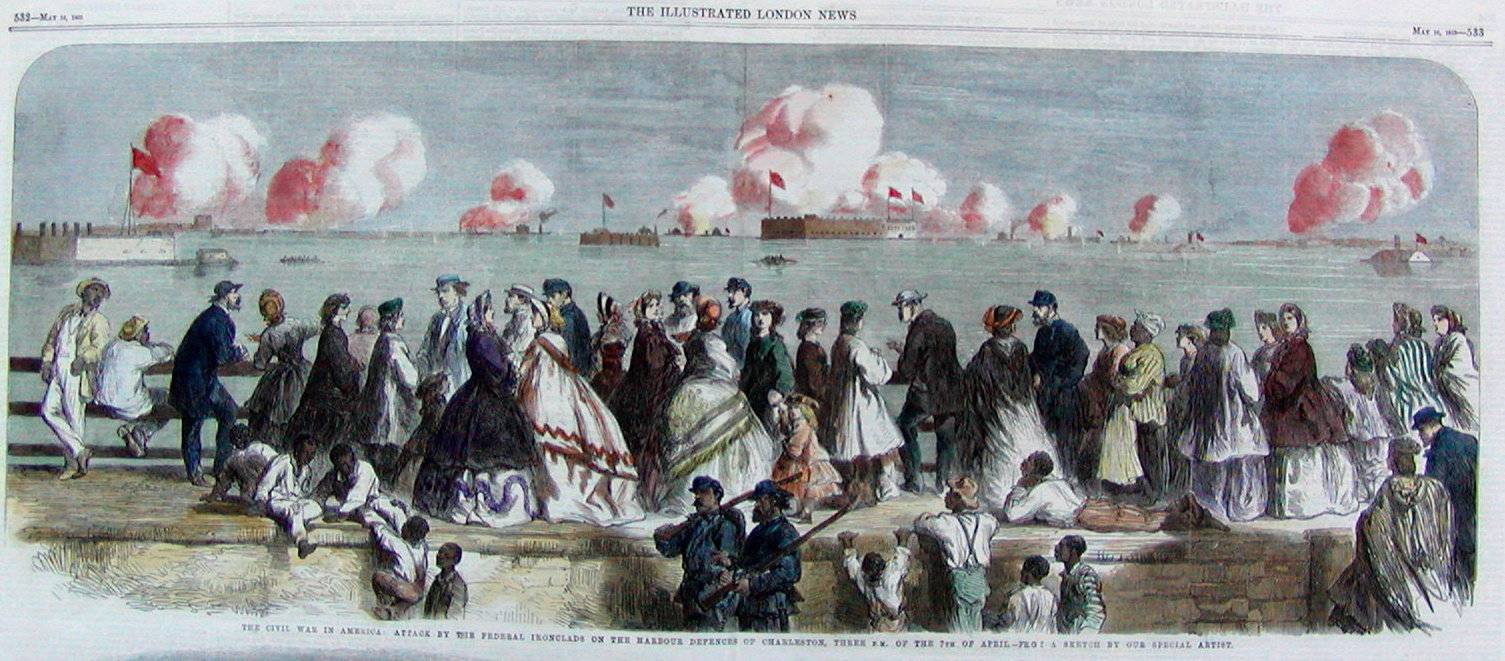

The bombardment of Sumter lasted 34 hours, with more than 3,000 shells hurled at the fort. Thousands of Charlestonians - men, women and children - crowded rooftops and the city wharves to watch the bombardment of Sumter. There were "prayers from the women and imprecations from the men; and then a shell would light up the scene." An eyewitness recorded the events of the Confederate assault. "Showers of balls from 10-inch columbiads and 42-pounders, and shells from [10-] inch mortars poured into the fort in one incessant stream…"

Federal surrender

As a hurricane of shot and shell fell on Fort Sumter, the Federal garrison grew weary. Even though the federals fired carefully at the many Confederate targets scattered around the Harbor, Anderson's limited munitions quickly dwindled. Food was also critically low.

To add to the garrison's woes, the barracks caught fire three times on the first day of fighting. Then on April 13, Confederate "hot shot" (solid cannonballs heated red hot) set fire to the officers' quarters and spread, endangering the powder magazines. By noon the fort was almost uninhabitable. Major Anderson realized there was no point in subjecting his hungry, exhausted and half-suffocated men to further pounding. Consequently, General Beauregard was successful in negotiating Anderson's official surrender.

On Sunday, April 14, 1861, Major Anderson and his garrison marched out of Fort Sumter with drums beating and colors flying. A Confederate boat waited to take them to join the Federal fleet outside Charleston Harbor. As they passed Cumming's Point, soldiers at the Confederate battery lined the beach, heads uncovered, in silent tribute to Sumter's defenders. Neither side knew what the future would hold.

The Confederates began at once to clean up the debris of battle and to strengthen the fort's defenses. It was a proud moment for the southerners when the first official flag of the Confederacy - the "Stars and Bars" - was run up the flagstaff, announcing to all that the Confederates were now in possession of Fort Sumter. During the next four years the fort would be pounded into rubble by Union forces but it would never again be surrendered.

Source Citation:

[Fort Sumter Museum Exhibit Text at Fort Sumter National Monument.] National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/fosu/index.htm