World War II and Pearl Harbor

After World War I, many countries were struggling financially. Conquering new lands and creating new colonies was a way that world powers hoped to restore the financial and national security that the war had destroyed. Western nations such as France, the United States, and Great Britain received new colonies and territories from the post-World War I treaties and sought to use imported goods and favorable trade from those territories to rebuild their destroyed economies. Although Japan was active as an Allied force during WWI, Japan's request for equality among all nations, regardless of race, during the post-war diplomatic negotiations at Versailles was not approved. Japan hoped to assert their importance to global affairs by mirroring Western colonization. Japan began claiming new colonies in the Pacific, southeast Asia, and China as early as 1931. In 1937, Japan invaded China and started a conflict that would last until World War II ended in 1945. During this time, The United States and the Soviet Union supported China. Japan officially joined World War II by invading French Indochina, a colony of Allied France in southeast Asia in 1940. In order to limit Japanese military capability and expansion, the United States discontinued all export of oil (among other war-related supplies) to Japan, implementing an oil embargo. As machines of war like planes, tanks, and boats during this period were heavily reliant on oil, the U.S. embargo was intended to dissuade further military action while the United States remained militarily neutral. To become economically independent of the Western Allied powers, Japan decided to attack their Pacific holdings and control them instead. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked, with specific targets like the Philippines, Guam, and Pearl Harbor. These targets were deliberately chosen because they were territories in the Pacific that were controlled by Western nations like the United States that had been acquired through colonization. On December 9, 1941, the United States entered World War II in response to the Japanese attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawai'i, which was a U.S. territory at the time.

As of 1941, there were about 120,000 people of Japanese descent living in the United States, two-thirds of whom were born citizens of the United States. Following the attack, roughly 1,200 Japanese immigrant men were immediately jailed as suspected saboteurs by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. After Pearl Harbor but before mass imprisonment, about 5,500 Japanese immigrants were detained and imprisoned. They were denied legal counsel and were imprisoned without evidence that they were actually a threat. According to the FBI, the Japanese American civilian population was not a substantial threat beyond these "saboteurs." Public opinion, however, was dramatically different. Strings of Japanese military victories in the Pacific coupled with the Pearl Harbor attack led to an increase in racism against and fear of Japanese and Japanese American people. Journalists and newspaper columnists stoked these fears.

Debate about the relocation and imprisonment of Japanese American people took place among the public and within the government. Government agencies like the Department of Justice were reluctant to relocate and jail Japanese American people due to legal and ethical concerns over the elimination of due process and the violation of the Bill of Rights. Additionally, much of the civilian population of Hawai'i also had Japanese ancestry, and imprisoning a majority of the islands' population would have hindered the economy. Hawai'i was placed under martial law after Pearl Harbor and was subjected to different standards throughout the war, as it had been claimed as a territory by the United States in 1898 and was not inducted as a state until 1959.

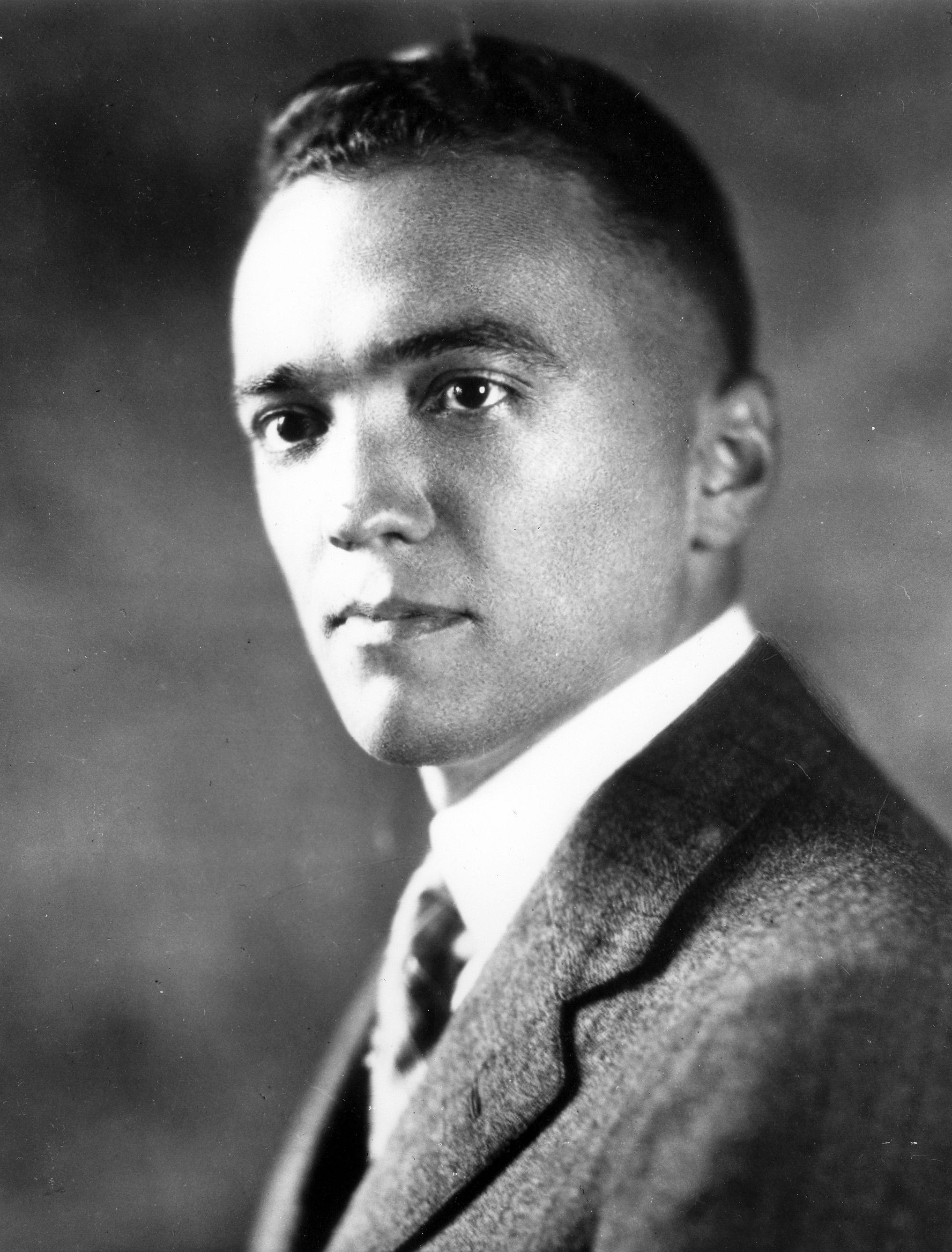

The United States War Department, headed by John J. McCloy, vocalized suspicions of sabotage by Japanese American people and recommended action, despite no hard evidence of any wrongdoing by people with Japanese lineage living in America or American territories. McCloy's proposed action to appease these baseless anti-Japanese fears was to place civilians of Japanese descent in prison camps inland, away from the west coast. The west coast in particular was a perceived risk, as it was closest to Japan and many assumed that it would be the first to be attacked by the Japanese due to its geographic proximity to the island. Due to unfounded suspicion and fear, Japanese American people were subject to surveillance before and during the war, such as secret wiretapping. Wiretapping involves a third-party, like the FBI, listening and recording private conversations between two people on a telegram, telephone, or other communication system. Community leaders were also subject to causeless detention by the FBI. Their assets, such as money in bank accounts, were also frozen and seized by the U.S. government. After Pearl Harbor, the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover became even more harsh toward Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans, as they imposed warrantless random raids on Japanese-owned homes. These raids were a direct violation of the Fourth Amendment, which protects against unwarranted raids or searches. Though the FBI violated constitutional rights in their raids and conduct, J. Edgar Hoover maintained that Japanese American civilians posed no threat to military operations and did not advocate for their relocation and imprisonment.

John J. McCloy

John J. McCloy