The Cherokee Nation in the 1820s

Cherokee culture thrived for thousands of years in the southeastern United States before European contact. When the Europeans settlers arrived, the different tribes they encountered, including the Cherokee, assisted them with food and supplies. The Cherokee taught the early settlers how to hunt, fish, and farm in their new environment. They introduced them to crops such as corn, squash, and potatoes; and taught them how to use herbal medicines for illnesses.

By the 1820s, many Cherokee people had adopted some of the cultural patterns of the white settlers as well. The settlers introduced new crops and farming techniques. Some Cherokee farms grew into small plantations, worked by enslaved people and their descendants originally brought from Africa. Cherokee people built gristmills, sawmills, and blacksmith shops. They encouraged missionaries to set up schools to educate their children in the English language. They used a syllabary (characters representing syllables) developed by Sequoyah (a Cherokee intellectual) to encourage literacy as well. In the midst of the many changes that followed contact with the Europeans, the Cherokee worked to retain their cultural identity operating "on a basis of harmony, consensus, and community with a distaste for hierarchy and individual power."1

In 1822, the treasurer of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions reported on some of the changes that had been made:

It used to be said, a few years since, with the greatest of confidence, and is sometimes repeated even now, that "Indians can never acquire the habit of labour." Facts abundantly disprove this opinion. Some Indians not only provide an abundant supply of food for their families, by the labour of their own hands, but have a surplus of several hundred bushels of corn, with which they procure clothing, furniture, and foreign articles of luxury.

2

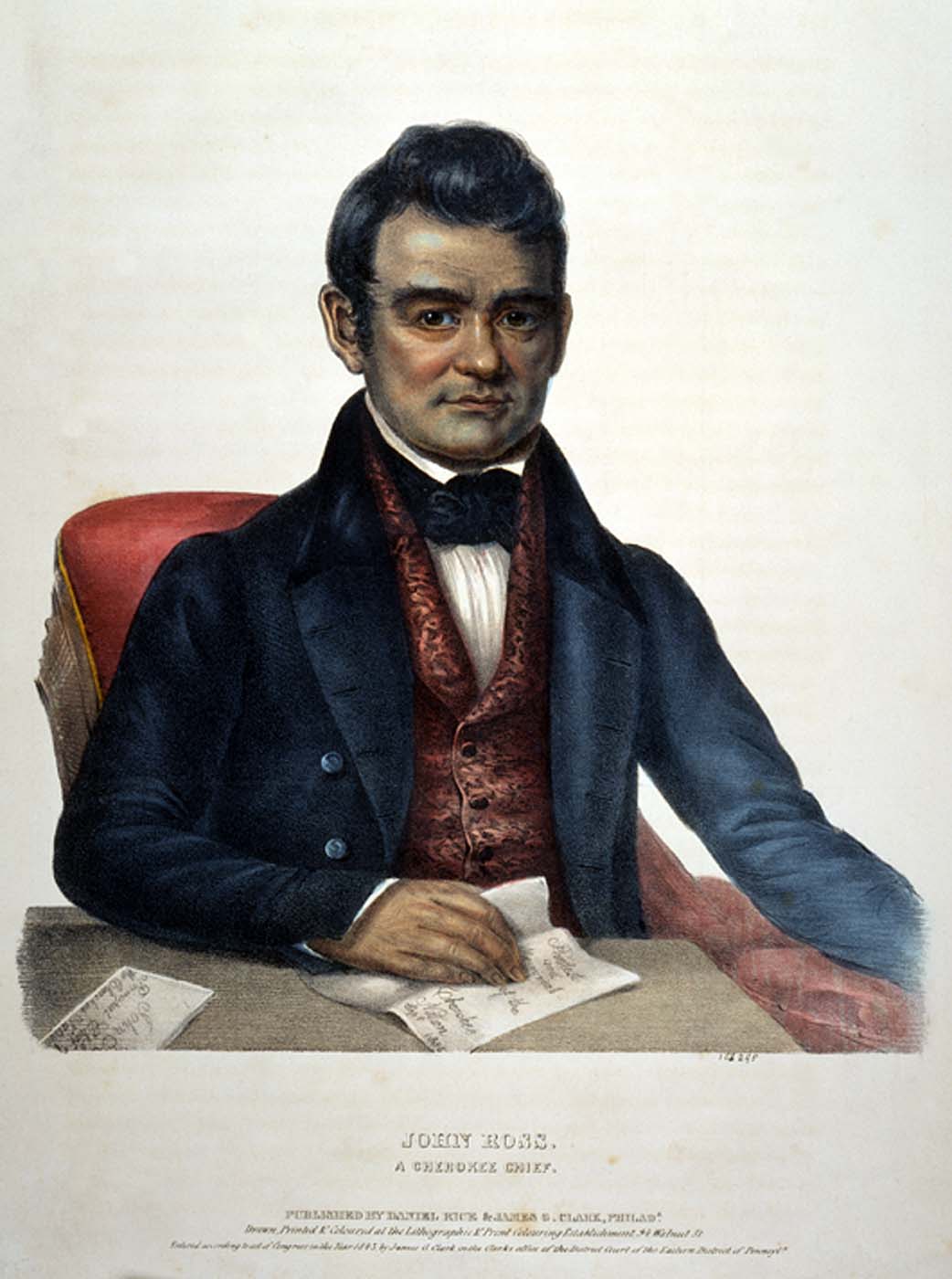

Two leaders played central roles in the destiny of the Cherokee. Both had fought alongside Andrew Jackson in a war against a faction of the Creek Nation which became known as the Creek War (1813-1814). Both had used what they learned from the white enslavers to also become enslavers and rich men. Both were descended from Anglo-Americans who moved into different tribes' territories to trade and ended up marrying American Indian women and having families. Both were fiercely committed to the welfare of the Cherokee people.

Major Ridge3 and John Ross shared a vision of a strong Cherokee Nation that could maintain its separate culture and still coexist with its white neighbors. In 1825, they worked together to create a new national capitol for their tribe, at New Echota in Georgia. In 1827, they proposed a written constitution that would put the tribe on an equal footing with the whites in terms of self government. The constitution, which was adopted by the Cherokee National Council, was modeled on that of the United States. Both men were powerful speakers and well able to articulate their opposition to the constant pressure from settlers and the federal government to relocate to the west. Ridge had first made a name for himself opposing a Cherokee proposal for removal in 1807. In 1824 John Ross, on a delegation to Washington, D.C. wrote:

We appeal to the magnanimity of the American Congress for justice, and the protection of the rights, liberties, and lives, of the Cherokee people. We claim it from the United States, by the strongest obligations, which imposes it upon them by treaties; and we expect it from them under that memorable declaration, "that all men are created equal."

4

Not all tribal elders or tribal members approved of the ways in which many in the tribe had adopted white cultural practices and they sought refuge from white interference by moving into what is now northwestern Arkansas. In the 1820s, the numbers of Cherokees moving to Arkansas territory increased. Others spoke out on the dangers of Cherokee participation in Christian churches, and schools, and predicted an end to traditional practices. They believed that these accommodations to white culture would weaken the tribe's hold on the land.

Even as Major Ridge and John Ross were planning for the future of New Echota and an educated, well-governed tribe, the state of Georgia increased its pressure on the federal government to release Cherokee lands for white settlement. Some settlers did not wait for approval. They simply moved in and began surveying and claiming territory for themselves. A popular song in Georgia at the time included this refrain:

All I ask in this creation Is a pretty little wife and a big plantation Way up yonder in the Cherokee Nation.

5

"You cannot remain where you now are...."

The Cherokees might have been able to hold out against renegade settlers for a long time. But two circumstances combined to severely limit the possibility of staying put. In 1828 Andrew Jackson became president of the United States. In 1830 -- the same year the Indian Removal Act was passed -- gold was found on Cherokee lands. There was no holding back the tide of Georgians, Carolinians, Virginians, and Alabamians seeking instant wealth. Georgia held lotteries to give Cherokee land and gold rights to whites. The state had already declared all laws of the Cherokee Nation null and void after June 1, 1830, and also prohibited Cherokees from conducting tribal business, contracting, testifying against whites in court, or mining for gold. Cherokee leaders successfully challenged Georgia in the U.S. Supreme Count, but President Jackson refused to enforce the Court's decision.

Most Cherokees wanted to stay on their land. Chief Womankiller, an old man, summed up their views:

My sun of existence is now fast approaching to its setting, and my aged bones will soon be laid underground, and I wish them laid in the bosom of this earth we have received from our fathers who had it from the Great Being above.

6

Yet some Cherokees felt that it was futile to fight any longer. By 1832, Major Ridge, his son John, and nephews Elias Boudinot and Stand Watie had concluded that incursions on Cherokee lands had become so severe, and abandonment by the federal government so certain, that moving was the only way to survive as a nation. A new treaty accepting removal would at least compensate the Cherokees for their land before they lost everything. These men organized themselves into a Treaty Party within the Cherokee community. They presented a resolution to discuss such a treaty to the Cherokee National Council in October 1832. It was defeated. John Ross, now Principal Chief, was the voice of the majority opposing any further cessions of land. The two men who had worked so closely together were now bitterly divided.

The U.S. government submitted a new treaty to the Cherokee National Council in 1835. President Jackson sent a letter outlining the treaty terms and urging its approval:

My Friends: I have long viewed your condition with great interest. For many years I have been acquainted with your people, and under all variety of circumstances in peace and war. You are now placed in the midst of a white population. Your peculiar customs, which regulated your intercourse with one another, have been abrogated by the great political community among which you live; and you are now subject to the same laws which govern the other citizens of Georgia and Alabama.

I have no motive, my friends, to deceive you. I am sincerely desirous to promote your welfare. Listen to me, therefore, while I tell you that you cannot remain where you now are. Circumstances that cannot be controlled, and which are beyond the reach of human laws, render it impossible that you can flourish in the midst of a civilized community. You have but one remedy within your reach. And that is, to remove to the West and join your countrymen, who are already established there. And the sooner you do this the sooner you will commence your career of improvement and prosperity.

7

John Ross persuaded the council not to approve the treaty. He continued to negotiate with the federal government, trying to strike a better bargain for the Cherokee people. Each side -- the Treaty Party and Ross's supporters -- accused the other of working for personal financial gain. Ross, however, had clearly won the passionate support of the majority of the Cherokee nation, and Cherokee resistance to removal continued.

In December 1835, the U.S. resubmitted the treaty to a meeting of 300 to 500 Cherokees at New Echota. Older now, Major Ridge spoke of his reasons for supporting the treaty:

I am one of the native sons of these wild woods. I have hunted the deer and turkey here, more than fifty years. I have fought your battles, have defended your truth and honesty, and fair trading. The Georgians have shown a grasping spirit lately; they have extended their laws, to which we are unaccustomed, which harass our braves and make the children suffer and cry. I know the Indians have an older title than theirs. We obtained the land from the living God above. They got their title from the British. Yet they are strong and we are weak. We are few, they are many. We cannot remain here in safety and comfort. I know we love the graves of our fathers. We can never forget these homes, but an unbending, iron necessity tells us we must leave them. I would willingly die to preserve them, but any forcible effort to keep them will cost us our lands, our lives and the lives of our children. There is but one path of safety, one road to future existence as a Nation. That path is open before you. Make a treaty of cession. Give up these lands and go over beyond the great Father of Waters.

8

Twenty men, none of them elected officials of the tribe, signed the treaty, ceding all Cherokee territory east of the Mississippi to the U.S. in exchange for $5 million and new homelands in Indian Territory. Major Ridge is reported to have said that he was signing his own death warrant.

The Treaty of New Echota was widely protested by Cherokees and by whites. The tribal members who opposed relocation considered Major Ridge and the others who signed the treaty traitors. After an intense debate, the U.S. Senate approved the Treaty of New Echota on May 17, 1836, by a margin of one vote. It was signed into law on May 23. As John Ross worked to negotiate a better treaty, the Cherokees tried to sustain some sort of normal life -- even as white settlers carved up their lands and drove them from their homes. Removal had become inevitable. It was simply a matter now of how it would be accomplished.

"Every Cherokee man, woman or child must be in motion..."

For two years after the Treaty of New Echota, John Ross and the Cherokees continued to seek concessions from the federal government, which remained disorganized in its plans for removal. Only the eager settlers with their eyes on the Cherokee lands moved with determination. At the end of December 1837, the government warned the Cherokee that the clause in the Treaty of New Echota requiring that they should "remove to their new homes within two years from the ratification of the treaty" would be enforced.9 In May, President Van Buren sent Gen. Winfield Scott to remove the people from their land. On May 10, 1838, General Scott issued the following proclamation:

Cherokees! The President of the United States has sent me, with a powerful army, to cause you, in obedience to the Treaty of 1835, to join that part of your people who are already established in prosperity, on the other side of the Mississippi. . . . The full moon of May is already on the wane, and before another shall have passed away, every Cherokee man, woman and child . . . must be in motion to join their brethren in the far West.

10

Federal troops and state militias began to move the Cherokees into stockades. In spite of warnings to troops to treat them kindly, the roundup proved harrowing. A missionary described what he found at one of the collection camps in June:

The Cherokees are nearly all prisoners. They have been dragged from their houses, and encamped at the forts and military posts, all over the nation. In Georgia, especially, multitudes were allowed no time to take any thing with them except the clothes they had on. Well-furnished houses were left prey to plunderers, who, like hungry wolves, follow in the trail of the captors. These wretches rifle the houses and strip the helpless, unoffending owners of all they have on earth.

11

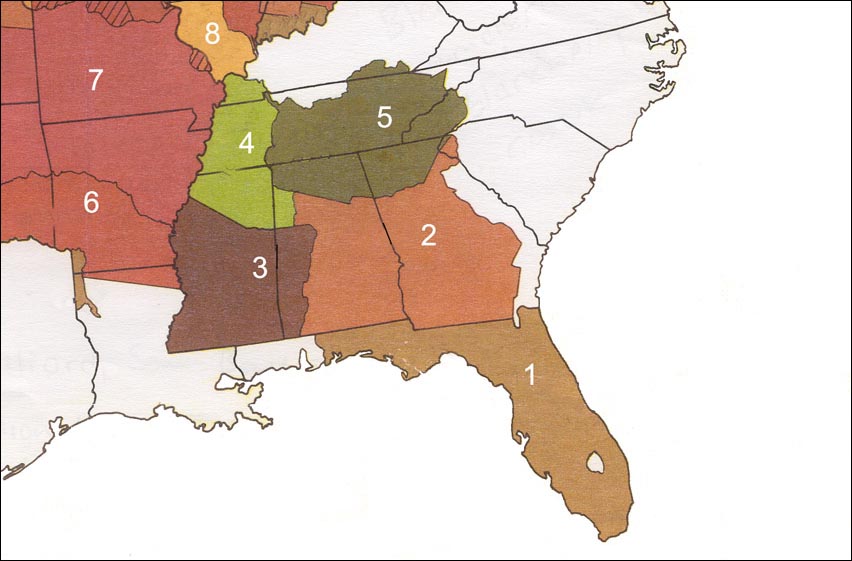

Three groups were removed by the Federal and militia soldiers in the summer, traveling from present-day Chattanooga by rail, boat, and wagon, primarily on the water route, but as many as 15,000 people still awaited removal. Sanitation was deplorable. Food, medicine, clothing, even coffins for the dead, were in short supply. Water was scarce and often contaminated. Diseases raged through the camps. Many died.

Those forced to leave and travelling over land were prevented from leaving in August due to a summer drought. The first detachments set forth only to find no water in the springs and they returned back to their camps. The remaining Cherokees asked to postpone removal until the fall. The delay was granted, provided they remain in the camps until travel resumed. The Army also granted John Ross's request that the Cherokees manage their own removal. The government provided wagons, horses, and oxen; Ross made arrangements for food and other necessities. In October and November, 12 detachments of 1,000 men, women, children, including more than 100 enslaved people, set off on an 800 mile-journey overland to the west. Five thousand horses, and 654 wagons, each drawn by 6 horses or mules, went along. Each group was led by a respected Cherokee leader and accompanied by a doctor, and sometimes a missionary. Those riding in the wagons were usually only the sick, the aged, children, and nursing mothers with infants.

The northern route, chosen because of dependable ferries over the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and a well-travelled road between the two rivers, turned out to be the more difficult. Heavy autumn rains and hundreds of wagons on the muddy route made roads nearly impassable; little grazing and game could be found to supplement meager rations. Two-thirds of the Cherokees were trapped between the ice-bound Ohio and Mississippi rivers during January. A traveler from Maine happened upon one of the caravans in Kentucky:

We found the road literally filled with the procession for about three miles in length. The sick and feeble were carried in waggons . . . a great many ride horseback and multitudes go on foot—even aged females, apparently nearly ready to drop into the grave, were traveling with heavy burdens attached to the back—on the sometimes frozen ground, and sometimes muddy streets, with no covering for the feet except what nature had given them.

12

A Cherokee survivor later recalled:

Long time we travel on way to new land. People feel bad when they leave Old Nation. Women cry and made sad wails. Children cry and many men cry, and all look sad like when friends die, but they say nothing and just put heads down and keep on go towards West. Many days pass and people die very much.

13

In 1972, Robert K. Thomas, a professor of anthropology from the University of Chicago and an elder in the Cherokee tribe, told the following story to a few friends:

Let me tell you this. My grandmother was a little girl in Georgia when the soldiers came to her house to take her family away. . . . The soldiers were pushing her family away from their land as fast as they could. She ran back into the house before a soldier could catch her and grabbed her [pet] goose and hid it in her apron. Her parents knew she had the goose and let her keep it. When she had bread, she would dip a little in water and slip it to the goose in her apron.

Well, they walked a long time, you know. A long time. Some of my relatives didn't make it. It was a bad winter and it got really cold in Illinois. But my grandmother kept her goose alive.

One day they walked down a deep icy gulch and my grandmother could see down below her a long white road. No one wanted to go over the road, but the soldiers made them go, so they headed across. When my grandmother and her parents were in the middle of the road, a great black snake started hissing down the river, roaring toward the Cherokees. The road rose up in front of her in a thunder and came down again, and when it came down all of the people in front of her were gone, including her parents.

My grandmother said she didn't remember getting to camp that night, but she was with her aunt and uncle. Out on the white road she had been so terrified, she squeezed her goose hard and suffocated it in her apron, but her aunt and uncle let her keep it until she fell asleep. During the night they took it out of her apron.

14

On March 24, 1839, the last detachments arrived in the west. Some of them had left their homeland on September 20, 1838. No one knows exactly how many died during the journey. Missionary doctor Elizur Butler, who accompanied one of the detachments, estimated that nearly one fifth of the Cherokee population died. The trip was especially hard on infants, children, and the elderly. An unknown number of enslaved people also died on the Trail of Tears. The U.S. government never paid the $5 million promised to the Cherokees in the Treaty of New Echota.

- 1. D. W. Meinig, The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Vol. 2, Continental America, 1800-1867 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 88.

- 2. John Ehle, Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 177.

- 3. Like many Cherokees, Ridge originally had only one name. He later adopted the title of Major, which he earned during the War of 1812, as his first name.

- 4. Gary E. Moulton, ed., Papers of Chief John Ross (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), I:76-78; cited in Stanley W. Hoig, The Cherokees and Their Chiefs: In the Wake of Empire (Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1998), 130.

- 5. Samuel Carter, III, Cherokee Sunset: A Nation Betrayed (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1976), 72, cited in Ehle, Trail of Tears, 224.

- 6. Cherokee Phoenix October 28, 1829, cited in Ehle, Trail of Tears, 224.

- 7. Allegheny Democrat March 16, 1835, quoted in Ehle, Trail of Tears, 275-278.

- 8. Thurman Wilkins, Cherokee Tragedy: The Story of the Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People (New York: Macmillan, 1970), 276-77, quoted in Ehle, Trail of Tears, 294.

- 9. Journal of Cherokee Studies 3:3 (1978), 134-5, cited in Ehle, The Trail of Tears, 319.

- 10. Journal of Cherokee Studies 3:3 (1978), 145, cited in Ehle, The Trail of Tears, 324-5.

- 11. Baptist Missionary Magazine 18 (Sep. 1838), cited in Hoig, The Cherokees and Their Chiefs, 167.

- 12. New York Observer, January 26, 1839, cited in Ehle, The Trail of Tears, 358.

- 13. Oklahoman, April 7, 1929, cited in Ehle, The Trail of Tears, 358.

- 14. Recorded by Kathleen Hunter, 1972.