There are many politicians that are difficult to figure out. Sometimes what they say they believe in conflicts with their public actions. Some appear to be mean spirited, conveying words and actions that are hateful. Others have views that seem to conflict with each other. For example, some politicians support programs for the poor and weak but have also held racist views and have supported racist policies. North Carolina has had its share of historical figures that are difficult to figure out or interpret. This status makes them complicated historical people. Sam Ervin was one of those complicated people.

Sam Ervin was one of the most notable North Carolinians of the 20th century. He was born in Morganton, North Carolina, on September 27, 1896. After serving in the First World War, Ervin went to school at the University of North Carolina. He then attended Harvard University. Ervin earned a law degree from Harvard in 1922. He became known as a "country lawyer" who liked to tell folksy stories in court.

Ervin's political career began in 1922 when he was elected to the North Carolina House of Representatives. He served as a state congressman for six years and as a federal congressman for one year. Ervin then became a justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1948. He remained on the court for several years until he was appointed as a United States Senator in 1954. Ervin would stay in that role for over twenty years.

Ervin's time as a United States Senator is remembered for two positions he took. One was as an opponent of civil rights. Ervin opposed the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954. He also argued against the 1964 Civil Rights Act. This important law said that businesses and public spaces could not treat people differently because of the color of their skin. When asked to explain his opposition to civil rights laws in 1966, he said that they were unconstitutional. Ervin also said that civil rights laws "pick out one group of Americans and give them rights superior to those ever sought by or granted to any other Americans, at the expense of the whole entire body of Americans." His view was biased given the centuries of unfair treatment that African Americans had experienced up to that point.

Ervin was known as an opponent of civil rights. But he was also a supporter of civil liberties such as freedom of speech and religion. Ervin first became known as a civil liberties advocate in 1925. In that year, he helped defeat a law banning the teaching of evolution. As a senator, he opposed a constitutional amendment that would have allowed prayer in schools. Ervin helped defeat that amendment in 1966. Ervin also served on two important committees in the history of civil liberties. One committee investigated Joseph McCarthy in 1954 and the other targeted Richard Nixon in 1973. The McCarthy investigation helped to end the Second Red Scare, which had limited freedom of expression.

While his investigation of McCarthy was important, Ervin's role as committee chair in the Nixon investigation became legendary. Nixon had spent years spying on his opponents and breaking into their offices. Congress started investigating the president in 1973. Ervin was tapped to lead the investigation. Ervin's hearings revealed the Oval Office tapes that helped end the Nixon presidency. Ervin became famous because of his knowledge and his folksy manner in the televised hearings. Despite his support of many of Nixon's policies, Ervin distrusted the president and his attempts to spy on his opponents. Ervin told his private secretary Rufus Edmisten, "You know, Richard Nixon is just scared to death of freedom. He's scared to death of the term 'freedom,' for people to say what they want to say and do what they want to do."

Ervin served three terms in the United States Senate, retiring in 1974. He went back to Morganton, worked as a lawyer, and recorded an album of songs and humorous stories before his death in 1985. Ervin was remembered by the mayor of Morganton as a great leader but also as a good person: "He was just plain folks. There was no pretense about Sam." Ervin's son and his grandson both served as judges. Senator Ervin's secretary, Rufus Edmisten, later became a leader of state politics.

Questions for Discussion:

What are civil liberties?

What are civil rights?

What are the similarities between civil rights and civil liberties?

How are civil rights and civil liberties different?

Why might Ervin's views and policies be seen as contradictory?

How might you interpret or figure out Ervin's political views and policies?

References:

Campbell, Karl E. Senator Sam Ervin, Last of the Founding Fathers. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Grele, Ronald. Sam J. Ervin, Jr. Oral History Interview - JFK#1, 5/17/1966, transcript of an oral history conducted 1966 by Ronald Grele, John F. Kennedy Library Oral History Program, Washington, D.C., May 17, 1966, https://www.jfklibrary.org/sites/default/files/archives/JFKOH/Ervin%2C%2...

Minehart, Tom. "Senator Sam' Ervin Comes Home to Morganton," AP News, April 24, 1985,https://web.archive.org/web/20220526084535/https://apnews.com/9f959967f9...

"Rufus Edmisten: Staff to Senator Sam Ervin, N.C., Subcommittee on Separation of Powers, Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights, and Deputy Chief Counsel, Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities (Watergate Committee) (1964-1974)," Oral History Interviews, May 24, 2011 to August 28, 2012, Senate Historical Office, Washington, D.C.

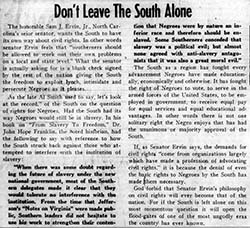

Don't Leave the South Alone

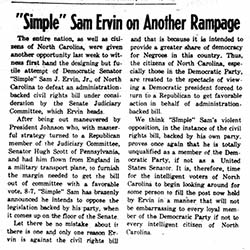

Don't Leave the South Alone Simple Sam Ervin on Another Rampage,

Simple Sam Ervin on Another Rampage,