In his farewell address before leaving office, President George Washington warned his countrymen to remain neutral in European affairs and to avoid alliances that might drag the young nation into devastating wars. But by the first decade of the 1800s, it was becoming impossible for the United States to stay out of European wars.

After the French Revolution, which began in 1789, Great Britain and France fought — again — for dominance in Europe. During their wars, each nation blockaded the other to cut off its trade, and each used its navy to seize foreign ships on the open seas attempting to reach the other nation with trade goods. Since the United States remained neutral, its merchant ships traded with both nations — and the navies of both nations attacked American ships. After 1803, British ships began stopping U.S. merchant ships on the open seas and impressed British-born U.S. citizens into the Britsh navy, claiming that the sailors were deserters. In 1807, the British H.M.S. Leopard bombarded and forcibly boarded the U.S.S. Chesapeake off Norfolk, Virginia, in search of British navy deserters.

In 1807 President Jefferson responded by cutting off trade, first with all European nations and then only with Britain and France. But this "Non-Intercourse Act" was impossible to enforce, and didn't hurt the economies of the two warring nations as much as Jefferson had hoped. People in New England, where the economy depended on trade with Britain, protested. In 1810, Congress — spurred by North Carolina representative Nathaniel Macon — offered to reopen trade with whichever nation agreed to respect the rights of U.S. ships and sailors on the high seas. The French emperor Napoleon agreed first, even though he had no intention of keeping his promise, and the agreement between the U.S. and France angered Britain, which continued to blockade neutral commerce and impress American sailors.

Madison finally made the issue of impressment from ships sailing under the U.S. flag a matter of national sovereignty, arguing that if a foreign power could seize American ships and kidnap American citizens, the United States was essentially powerless. On June 1, 1812, he asked Congress for a declaration of war against Britain. Federalists, who tended to support Britain, were outraged, but the Republican majority in Congress declared war.

Unfortunately for the United States, British troops in Europe were about to be freed up for war in America. The same month the U.S. declared war on Britain, Napoleon invaded Russia, and though he took Moscow, he lost 90 percent of his army retreating through the horrible Russian winter that followed. With fewer French to fight, British troops sailed for America. The British blockaded the east coast, attacked Washington, and burned the White House. Many Republicans had seen the war as a chance to capture British and Spanish territory in North America, and U.S. troops invaded Canada but were defeated. American forces did win victories on Lake Champlain, and at Baltimore and Detroit, but the British took territory in Maine and around the Great Lakes.

By 1814 neither side could claim clear victory, and the two nations sent diplomats to negotiate peace. On December 24, they signed the Treaty of Ghent, which restored political boundaries in North America, established a boundary commission to resolve disputes over territory between the U.S. and Canada, and arranged peace with Indian nations on the frontier. With Napoleon defeated, the causes of the war — impressment and blockade of trade — were no longer an issue.

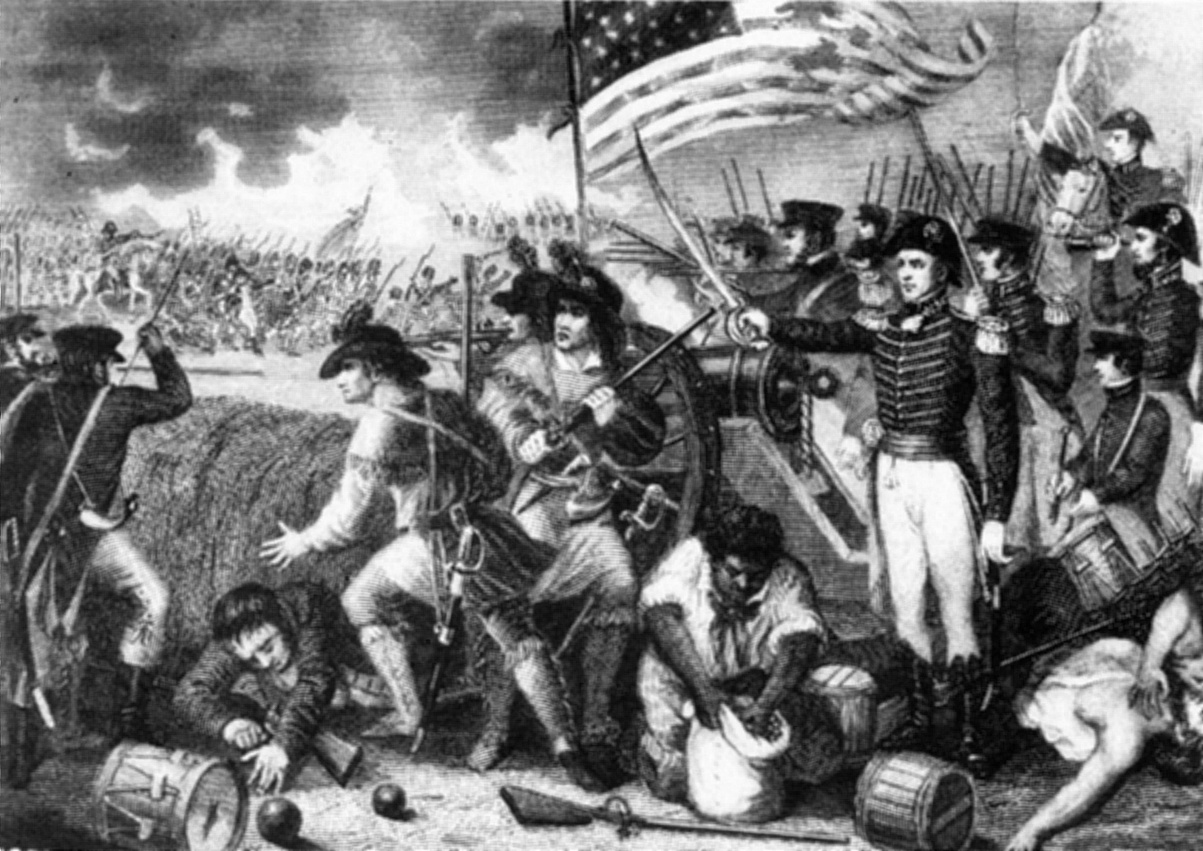

Ironically, the most memorable battle of the war was fought two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent was signed, but before news of it reached the U.S. British troops on board ships in the Gulf of Mexico came ashore to take New Orleans, and in a major battle on January 8, 1815, an American army led by Major General Andrew Jackson soundly defeated the British. More than two thousand British soldiers were killed, wounded, captured, or missing, while the American forces lost only a hundred men. The victory helped cheer a nation tired of war, and the fame Jackson earned helped propel him to the Presidency a decade later.

Historians debate who really "won" the War of 1812 and whether the United States gained anything from it. The war was hugely expensive; the burning of the capital was embarrassing, and the one thing the U.S. gained — freedom of the seas — would have come with the end of the Napoleonic Wars anyway. But some people have called the War of 1812 the Second War for Independence, because it established that the nation would — and could — defend itself when its sovereignty was threatened, and the war probably made clear to Britain that it wasn't worth insulting its former colonies.