By April of 1955, state leaders had determined that integration of the state's public schools was inevitable, so rather than resist the change ordered by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, the North Carolina General Assembly and Governor Luther Hodges determined that moderation and slow speed were the best approach. An all-white commission headed by a Rocky Mount businessman and former speaker of the state House of Representatives, Thomas Pearsall, convened to address the continuing issue of school desegregation following the state's anti-integration Pupil Assignment Act. The result of the commission's work was a legislative package and proposed amendment to the state Constitution that continued to give authority for school assignment to local districts and created a school choice plan that favored white families. The whole aim of the plan was to continue to stall the pace of integration of the state's public schools. The proposed amendment to the North Carolina's Constitution was overwhelmingly approved by the state's voters.

The Plan allowed the state to pay for students to attend private schools with vouchers if parents did not want their children to attend an integrated school. And it included an amendment to the North Carolina's Compulsory Attendance Law, providing that students could be excused from attending if they did not want to go to an integrated school and no other options were available. The Plan also gave the state the authority to close down a school if it determined intolerable conditions were present because of the effects of school desegregation. The overall goal of the Plan was to continue to stall the pace of school integration

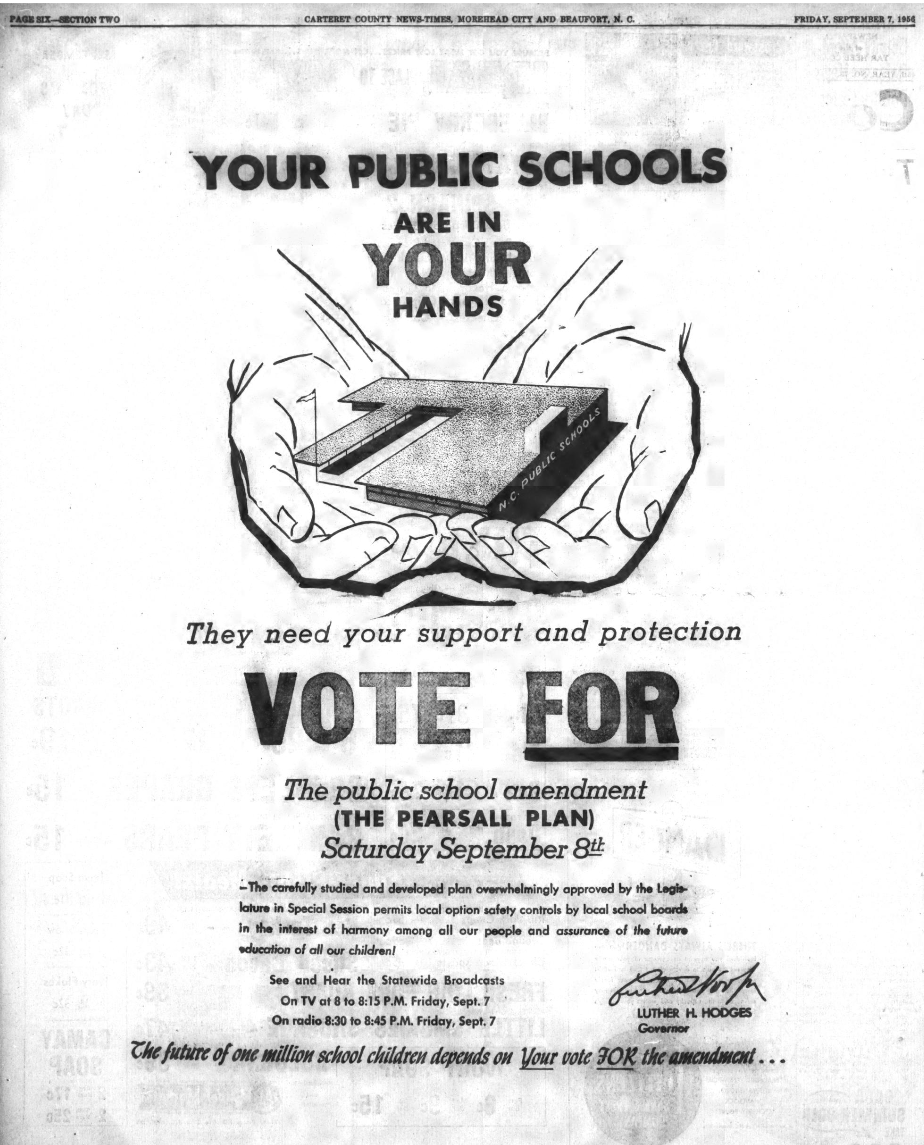

In May of 1956, black activists and organizations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), began to reject the Pearsall Plan. The North Carolina Teachers Association and community organizations mobilized thousands of members to voice strong opposition to the Pearsall Plan and to condemn the Pearsall Commission for not having any black members. In a special session of the General Assembly, John Hervey Wheeler, a black businessman and civil rights leader, argued the Pearsall Plan would be devastating to North Carolina's education system and business environment. Wheeler's argument was not well received and the Pearsall Plan was passed by a four-to-one margin. The passage of the Pearsall Plan was backed by a campaign arranged by Governor Hodges and his supporters which included radio and television. Winston-Salem was the only city in the state that rejected the educational amendments.

Despite the widespread support by politicians and white voters for the Pearsall Plan, no districts in the state ever implemented its provisions, and it was ultimately declared unconstitutional in 1969. In 1968, black parents in Johnston County sought legal relief from racial discrimination in the county's public schools in Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education. The ruling in 1969 declared the Pearsall Plan violated the state's constitution and also ruled that the duty to transition from a dual system was shared by local boards and state agencies such as the Department of Public Instruction. A young black lawyer named Julius Chambers was part of the team arguing for the plaintiffs (the parents). Chambers would go on to argue many more civil rights cases and work for the NAACP.

Although the Pearsall Plan was never implemented in North Carolina, public schools in districts throughout the state remained segregated through the policies of local communities, their school boards, and persistent patterns of neighborhood segregation. For schools and school systems that did integrate, one dire and ironic consequence was the loss of jobs for black teachers as historically black schools closed.