On the afternoon of March 15, 1781, American and British forces clashed for several hours near Guilford Courthouse. The battle was the culmination of several months of hard campaigning by the armies of Nathanael Greene and Charles Cornwallis. British strategy centered on conquering the South by destroying Greene's army. Completely aware of the plan, Greene and other American leaders refused to give Cornwallis a stand-up traditional fight, and instead engaged the British in several violent skirmishes and strategic retreats. Prior to Guilford Courthouse, the American strategy had resulted in the defeat of two detachments of Cornwallis's main army at King's Mountain in October 1780 and at Cowpens the following January.

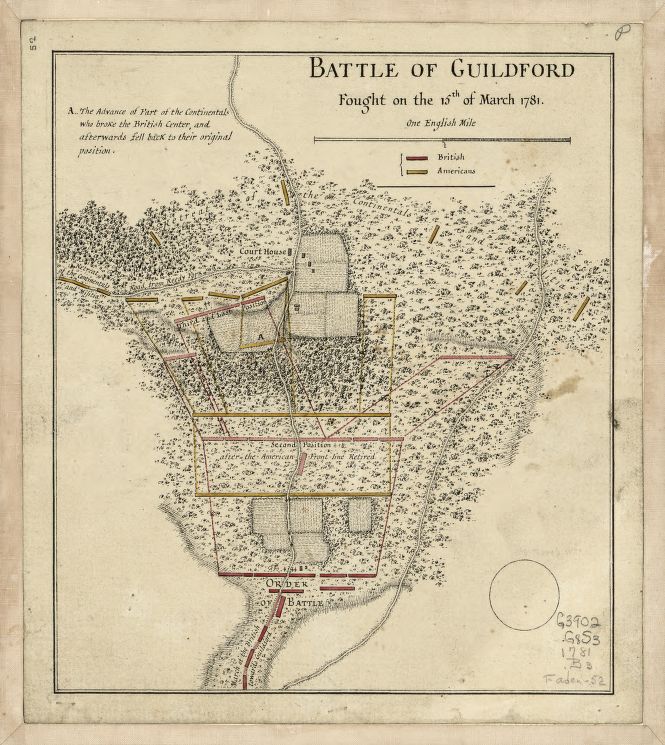

Greene deployed his army that morning in three lines, each spaced approximately 400 yards apart. The first consisted of nearly 800 North Carolina militia arranged on the edge of a field with "their arms resting on a rail fence." The North Carolina militiamen included William R. Davie, Benjamin Williams, Nathaniel Macon, James Turner, and David Caldwell. Nearly 850 Virginia militiamen stood as a second line within dense woods to the rear of the North Carolinians. The third line consisted of Greene's regulars, veteran Continental soldiers from Delaware, Maryland and Virginia.

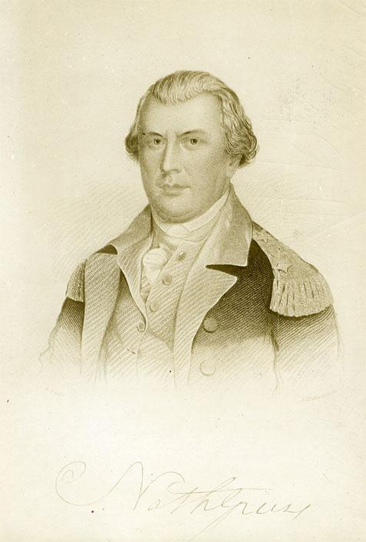

In addition, on the right and left flanks of the first line, Greene posted veteran Virginia and North Carolina riflemen, as well as Continental dragoons and infantry led by William Washington and Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee. Marquis De Bretigny, a French nobleman, lead a small detachment of North Carolina militia dragoons attached to Washington's force. Greene posted artillery at both the first and third lines, with those along the first having orders to fall back after the fighting began. Greene, following the example of Daniel Morgan at Cowpens earlier that year, ordered the North Carolina militia to fire two volleys and then fall behind the Virginians.

Several clashes erupted between British and American advance parties led by Banastre Tarleton and Light Horse Harry Lee at the New Garden Meeting House a few miles south of Greene's main army. British forces drove back the Americans and by noon Cornwallis was in striking distance of Greene's army.

Cornwallis's men advanced on Greene's first line after a thirty-minute artillery barrage by both sides. The British broke through the first and second lines relatively quickly, but suffered severe casualties in the advance, particularly along the Virginia militia line. One American noted that, after his regiment fired a volley, the British "appeared like the stalks of wheat after the harvest man passed over them with his cradleA wooden frame attached to a scythe, used for harvesting grain.." Despite the losses, Cornwallis's army pushed on to the American third line, where they engaged the Continental regulars in both small arms fire and hand-to-hand combat.

Unwilling to risk the destruction of his army, and aware that he had inflicted massive casualties on the British, Greene withdrew his army to Troublesome Ironworks, nearly fifteen miles away. The battered British army did not pursue. Twenty-seven percent of Cornwallis's army lay dead or wounded on the field. The Foot Guards battalions, considered the finest troops in the entire British army, suffered fifty-six percent casualties, including nearly all of their officers. In comparison, Greene lost only six percent of his force, the majority of whom were North Carolina and Virginia militia who had fled shortly after the battle began and been counted as missing in action. In a letter to Samuel Huntington, the president of Congress, Greene described the engagement as "long, obstinate and bloody."

Although Cornwallis's army held the field, the Americans had punished them severely. British Parliamentarian Charles James Fox told the House of Commons, "Another such victory would ruin the British army." After the battle Cornwallis withdrew his army first to Ramsey's Mill and then to the British base at Wilmington, where he resupplied his army. In late April Cornwallis marched for Virginia, where in October 1781 he would surrender his army to George Washington at Yorktown.