After the fall of Mobile, Alabama, in August 1864, Wilmington, North Carolina, became the last major Confederate seaport open to blockade-running traffic. Throughout the war, Wilmington had thrived as a hub for Southern maritime trade. Despite a vigilant Union naval blockade, profit-minded traders successfully smuggled foreign goods and munitions of war into Wilmington. The sleek, shallow-draft steamers unloaded their wares at the docks in exchange for cotton, naval stores, and lumber. Ships used to run the blockade had a shallow draft, meaning that very little of the hull was beneath the surface of the water. These ships could more easily navigate the barrier islands and shoals off Wilmington than the bigger Union ships trying to stop them.

From Wilmington, military provisions were then funneled straight to Virginia (heart of the war's Eastern Theatre) via the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad. In the final year of the conflict, as the noose tightened on the dying Confederacy, Wilmington anchored a tenuous lifeline for Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

By late summer 1864, Union policy makers began to focus their attention on the "city by the sea." In assessing Wilmington's illicit trade and the link to Lee's army, U.S. navy Secretary Gideon Welles deemed Wilmington "more important, practically" than the capture of the Confederate capital at Richmond. Welles pushed for a combined army-navy strike to topple Wilmington and the vast network of river defenses guarding her estuary.

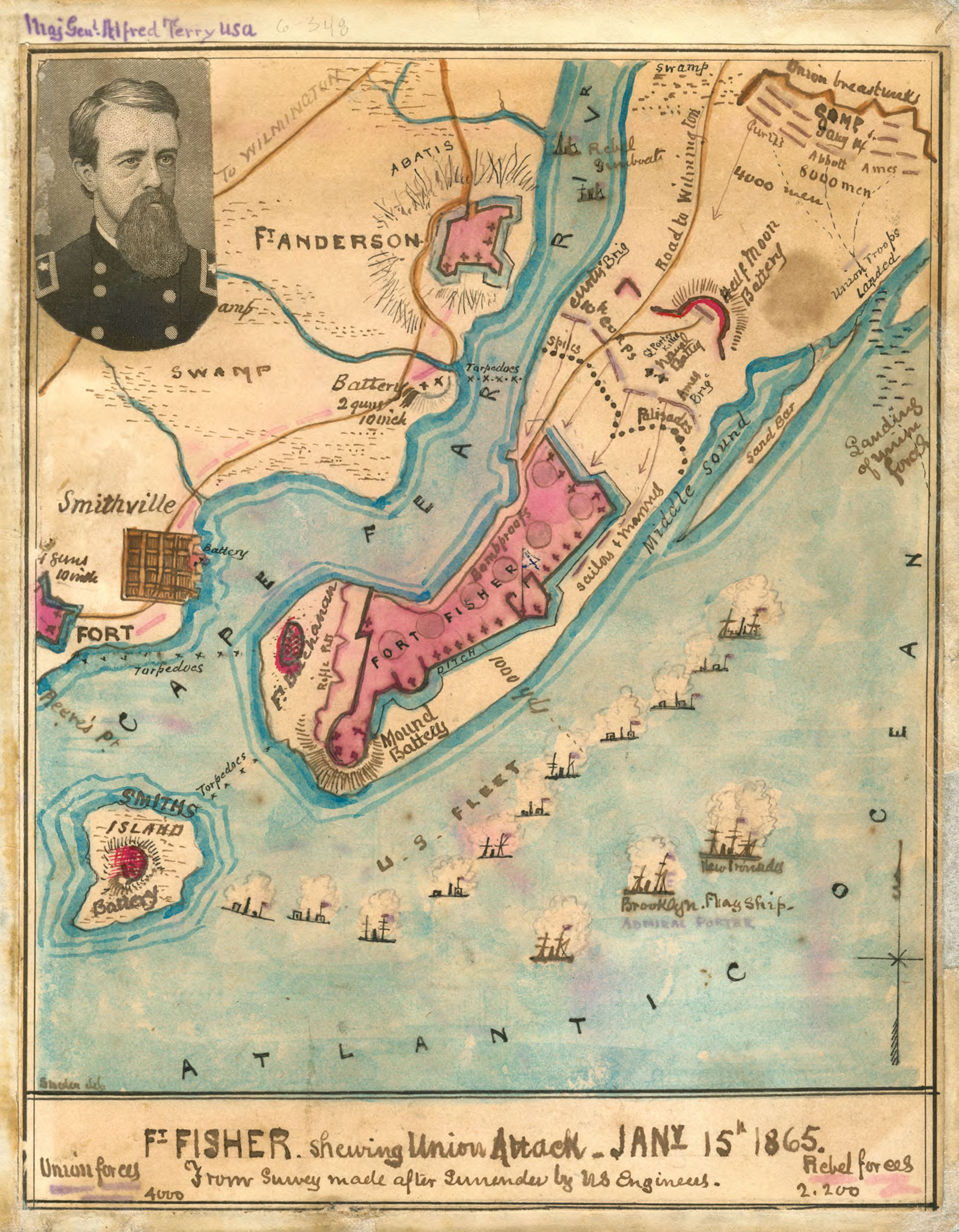

The key to these defenses was Fort Fisher — the largest earthen fort in the Confederacy. Commanded by Col. William Lamb, the massive 47-gun bastion protected New Inlet at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, twenty miles below the docks at Wilmington. Fisher communicated with incoming blockade-runners through a system of signal lights, and her guns dueled with Union blockaders on a regular basis. Secretary Welles understood that Fisher had to be captured in order to choke Lee's supply line. President Abraham Lincoln and Union general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant agreed.

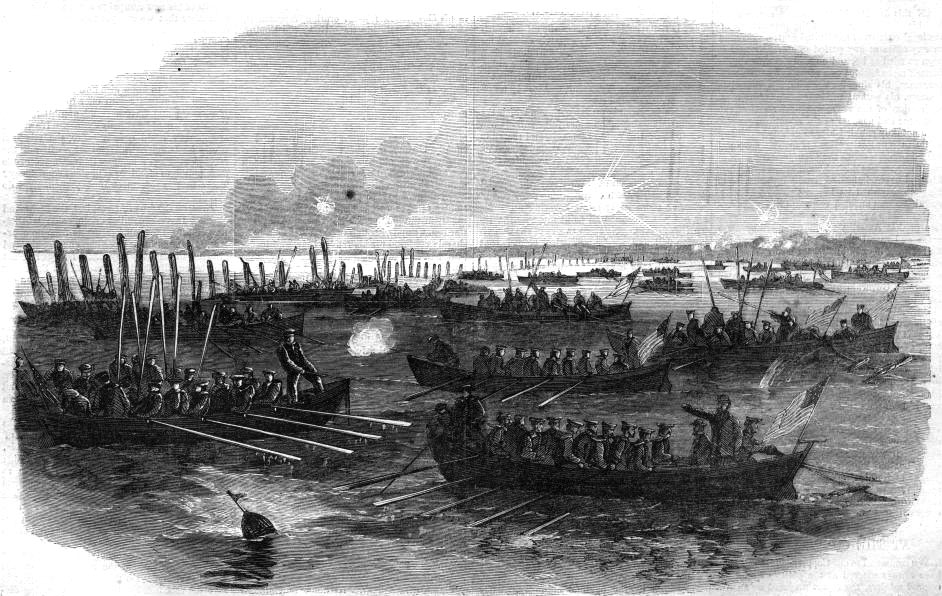

In December, U.S. army ground forces from the Army of the James, supported by an armada of 64 warships of the Union Navy, sailed to Cape Fear to attack Fort Fisher. On Christmas Eve 1864, Adm. David D. Porter's ships and ironclads unleashed the largest naval bombardment of the Civil War. More than 20,000 rounds of solid shot and exploding shell rained on Fisher from the ocean. On Christmas Day, army troops under major generals Benjamin Butler and Godfrey Weitzel made an amphibious landing on the beach at Federal Point, but the attack stalled after a brief clash with the fort's defenders.

Angered by the failure, Grant sent another expedition to Cape Fear in January 1865. This time, the commander of army ground forces was Maj. Gen. Alfred H. Terry. With 58 warships, Porter's armada hurled another 20,000 projectiles onto Fort Fisher. Terry's infantry and a naval shore contingent stormed the mighty bastion. After a savage hand-to-hand engagement, the Confederate garrison surrendered on the night of January 15. Both expeditions together resulted in nearly 4,000 casualties on both sides.

With Fort Fisher under Union control, Confederate forces quickly evacuated the remaining defenses of the lower Cape Fear. In February, army reinforcements under Maj. Gen. John Schofield marched on Wilmington. In a three-pronged offensive, Union troops advanced up the east and west banks of the Cape Fear River, with Admiral Porter's shallow-draft gunboats bringing up the center. After engagements at Sugar Loaf, Fort Anderson, and Forks Road, Union forces occupied Wilmington on February 22, 1865.

Having mounted a lackluster defense of Wilmington, Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg withdrew his forces (including remnants of the Cape Fear garrisons) toward Goldsboro. As Wilmington fell, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's army of 60,000 Union veterans blazed through South Carolina. Bragg's troops, with others under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, would soon engage in a final bloody showdown with Sherman in the Old North State.

With the capture of Fort Fisher and Wilmington, Union forces hammered one of the final nails into the coffin of the Confederacy. Lee's supply line was cut, and the war ended three months later.

Source Citation:

"The Civil War at Ft. Fisher." North Carolina Historic Sites. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://historicsites.nc.gov/all-sites/fort-fisher/history/civil-war-ft-....