When the Nineteenth Amendment came before the North Carolina legislature in August 1920, it was not the first time the state's leaders had considered allowing women to vote. In February 1897, a bill for women's suffrage had been introduced in the state senate by J.L. Hyatt, a Republican from Yancey County. This bill died after it was referred to the committee on psychiatric hospitals, of which Hyatt was the chair. Representative D.M. Clark of Pitt County introduced a bill in 1913 that would have allowed individual municipalities to vote on local women's suffrage, but it was eventually tabled. Women's right to vote came before the Assembly again in January 1915, when bills were introduced simultaneously in the House and Senate. After a joint committee hearing, the House voted to table the issue indefinitely and a few weeks later the Senate followed suit. Two years later, three separate women's suffrage bills were introduced. A municipal suffrage bill introduced by Gallatin Roberts of Buncombe County received a favorable committee report, but was ultimately defeated on the House floor. G. Ellis Gardner of Yancey County submitted a bill to allow suffrage via a constitutional amendment, but it was tabled. The third, which was introduced by state senator Thomas A. Jones of Buncombe County and called for limited voting rights for women, was defeated by a close 20-24 margin. In early 1919, women's suffrage was a major issue both locally and nationally, and bills for municipal suffrage were introduced in both houses of the North Carolina legislature. This time the bill passed in the Senate (35-12), but the House failed to pass it by a slim margin (49-54).

Although women's suffrage bills continued to be tabled or rejected, the issue actually had a great deal of support within North Carolina. Among those officially endorsing suffrage were a wide variety of well-respected women's organizations, as well as the Southern Baptist Conference, Southern Methodist General Conference, and the North Carolina Farmers Union. Virtually all of the state's mainstream newspapers were sympathetic by 1919, and the issue also had vocal celebrity supporters like William Jennings Bryan, former governor Locke Craig, Lieutenant-Governor O. Max Gardner, and newspaper editor Josephus Daniels.

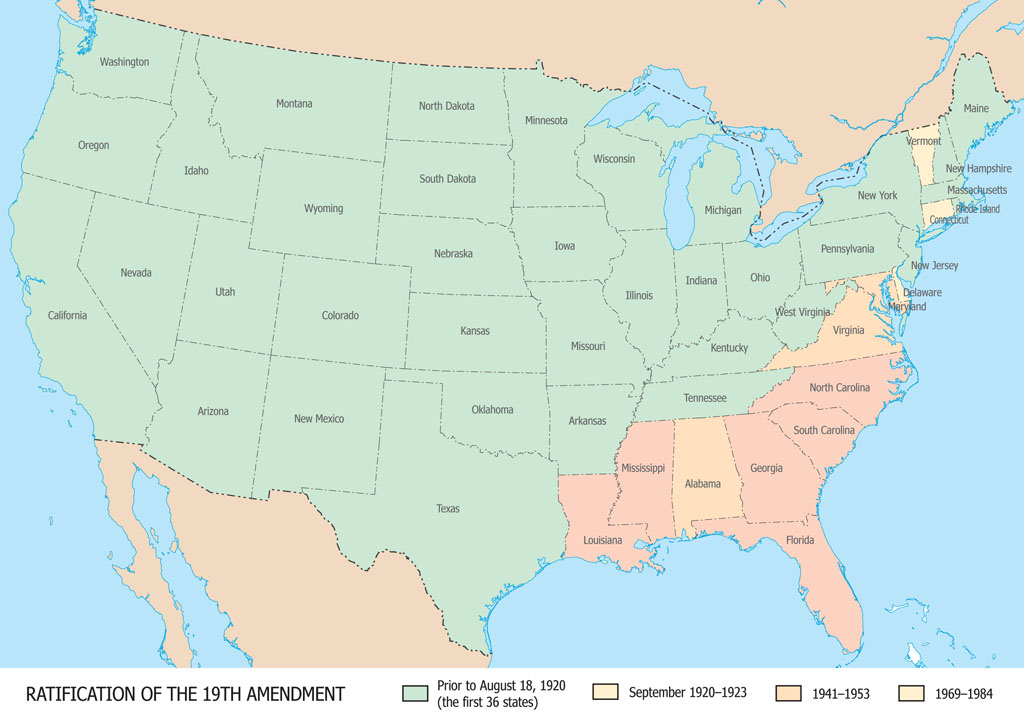

All of the states that were in the United States in 1920 eventually ratified the Ninteenth Amendment, but six southern states (including North Carolina) did not do so until 1969 or later.

In June 1919, the federal women's suffrage amendment—also known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment—was submitted to the states for ratification and by April 1920, 35 of the necessary 36 states had ratified. When the North Carolina legislature met on 10 August 1920, both North Carolina and Tennessee were considering the suffrage amendment and its ratification. It appeared not only that the Nineteenth Amendment would be ratified, but that North Carolina could be the final state required to do so.

Yet, on 11 August 1920, sixty-three of the one hundred and twenty North Carolina House members signed a telegram sent to the Tennessee legislature, promising that they—a majority of the House—would not ratify the amendment on the grounds that it interfered "with the sovereignty of Tennessee and other States of the Union," and asking that Tennessee do the same. The impact of this telegram seems to have been minimal, however, since the Tennessee State Senate passed ratification on the 13 August 1920. On the same day, Governor Thomas W. Bickett submitted a bill to the North Carolina legislature in a joint address to both houses. Although Bickett was against women's suffrage on principle, he felt that it was inevitable and that a North Carolina vote against ratification would only postpone the matter for a few months. He had previously written to President Woodrow Wilson, who was a supporter of women's suffrage, that he hoped Tennessee would ratify first, thus making a North Carolina vote unnecessary. In fact, the Raleigh News and Observer quoted the governor as saying to the Assembly, "I am profoundly convinced that it would be part of wisdom and grace for North Carolina to accept the inevitable and ratify the amendment."

On 17 August 1920, state senator Lindsay Warren proposed that the Senate postpone the ratification vote until the next legislative session. Warren's motion passed by a vote of 25 to 23, crushing any chance that North Carolina would be the final state in the ratification process. Two days later, the House openly rejected ratification by a vote of 41 to 71. Meanwhile, there was also ratification drama in Nashville, where shortly after the Tennessee House ratified the amendment, a motion was made to reconsider. By August 21, however, Tennessee upheld ratification by a unanimous 49 to 0 vote and, in spite of the objections voiced in North Carolina's legislature, women officially gained the right to vote in the United States.

Although North Carolina technically did not reject the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 (because of Warren's motion to table the bill in the Senate), it also did not ratify it until 1971, more than fifty years after it became law. The only state to wait longer was Mississippi, which ratified it in 1984.