When Virginia's expedition to the Ohio Valley was sent home by the French in 1754, Lieutenant-Governor Dinwiddie called on the governors of the other British colonies for help. The British government, knowing that tensions with France could easily erupt into violence, had authorized colonial governors to "draw forth the armed force of the Province, and... to repel Force by Force" -- but had strictly warned them "not to be the Agresor." Dinwiddie, taking a liberal view of his instructions, decided that the French refusal to give in to his demands was an act of force.

North Carolina joins the war

Only North Carolina responded to his call for help. North Carolina had a militia of citizens who were trained to fight if the colony was attacked -- but the militia was a shambles and was unable to operate inside the colony, much less outside of it. Matthew Rowan, who was acting governor until Arthur Dobbs could arrive from England, asked the assembly to raise a full-time military regiment of 750 men. The assembly agreed, but the colony could afford only 450 men.

The North Carolina Regiment marched slowly to Virginia under the command of James Innes. In 1741, Innes had been an officer in a major British offensive in South America, and so he was one of only a few men in North Carolina with military experience. In fact, so few colonists had military experience that when Innes arrived in Virginia, he was given command of the combined Anglo-American force, which consisted of troops from North Carolina and Virginia and a few British Regulars.

The North Carolinians were to rendezvous with Virginia's troops at Fort Cumberland on the Potomac River. But by the time they arrived, the Virginians , under the 22 year-old George Washington, had already been defeated by the French. Over the course of the summer, the North Carolina and Virginia forces slowly fell apart as the men deserted and left for home. Innes finally disbanded the regiment, but remained behind to fortify the post and prepare for another assault on the French.

Defending the frontier

Meanwhile, attacks by unknown Indians on the North Carolina frontier had raised the fears of colonists. Believing that the French were "daily instigating their Allies to scalp massacre and destroy our settlers," Governor Dobbs urged North Carolinians to fight. "In this critical situation," he told the provincial assembly, "let us his Majesty's faithful subjects of the Colony of No Carolina show that we are true sons of Britain whose ancestors have been ever famous for defending their valuable religion and liberties."1 The provincial assembly voted not only to send troops back to the Ohio Valley but to raise a company to protect the colony's own frontier. Appointed to command the company sent to the frontier was Hugh Waddell -- who had arrived in North Carolina only two years earler at the age of 19 but had served as a lieutenant in Innes' North Carolina Regiment.

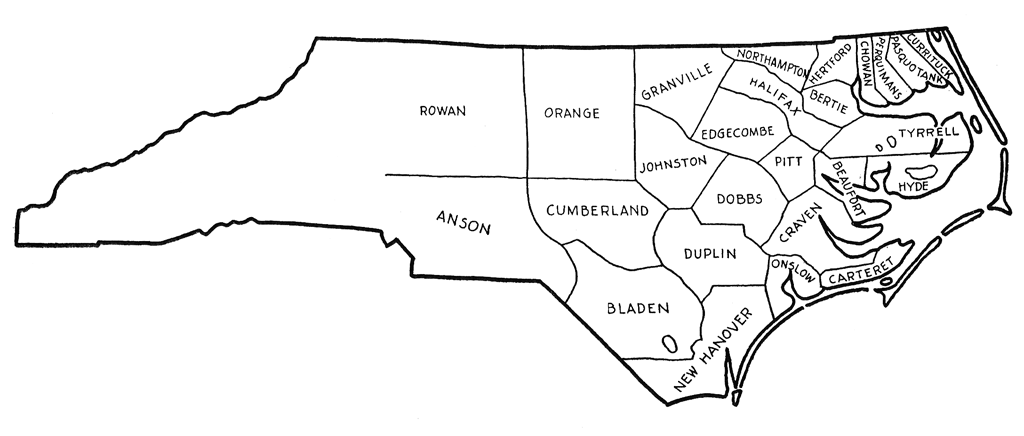

Waddell's company of 50 men marched west to the newly created county of Rowan in the summer of 1755. With Governor Dobbs, their first mission was "to fix upon a proper and most central place for them to winter at, and erect a Barrack, and afterwards, if found proper there to build a Fort." By the end of July, Dobbs and Waddell had chosen their site and begun construction of the fort that would come to be known as Fort Dobbs.

Fort Dobbs played a unique and important role in the French and Indian War even though it was never the site of a major battle, siege, or massacre. The fort served as military barracks, fortification, refuge, depot for provisioning troops, and center for negotiations with Indians. Fort Dobbs needed to assume all of these roles, because it was the only military installation between southern Virginia and South Carolina. It would also be North Carolina's contribution to a series of fortifications and military installations that would effectively define the western edge of British North America.

The site of Fort Dobbs was chosen because it was easily defensible and located on the frontier but not past it. Dobbs reasoned that "if I had placed [Waddell's company] beyond the Settlements without a fortification they might be exposed, and be no retreat for the Settlers, and the Indians might pass them and murder the Inhabitants, and retire before they durst go to give them notice."2

Only one description of the fort survives. In December 1756, commissioners appointed by the provincial assembly inspected the western defenses and reported that the fort was

a good and Substantial Building of the Dimentions following (that is to say) The Oblong Square fifty three feet by forty, the opposite Angles Twenty four feet and Twenty-Two In height Twenty four and a half feet as by the Plan annexed Appears, The Thickness of the Walls which are made of Oak Logs regularly Diminished from sixteen Inches to Six, it contains three floors and there may be discharged from each floor at one and the same time about one hundred Musketts."

3

For the next three years the assembly voted to keep troops at Fort Dobbs to protect settlers from brigands, Indians, and attacks by French soldiers. The fort also acted as the nerve center for the defense of western North Carolina. The militia of each county was ordered to choose 50 men and an officer who would join the men stationed at the fort should the French invade North Carolina.

Settlers were grateful for the protection the fort provided. In 1758, when the company stationed at Fort Dobbs was ordered north to fight the French, citizens begged the provincial government to keep the men in place. The Assembly received "a Petition of several of the Inhabitants of Rowan County, setting forth, That the murders lately committed on the Dan River hath occasioned the Inhabitants of the Forks of the Yadkin to leave their Settlements, &c., Praying the Continuance of Captain Bayley and his Company, or some other in his Room." 4 But the Assembly tabled the petition and resolved to send the company to war.

Fighting in the North

The company stationed at Fort Dobbs, by then under the command of Captain Andrew Bailey, was increased to 100 men in preparation for a major British offensive. Although they were slow to leave -- possibly because Bailey remained at Fort Dobbs to allay the fears of local residents -- by summer they were marching overland to Pennsylvania. There, they linked up with 200 more North Carolina soldiers under the command of Hugh Waddell, now a major. Waddell's men were part of a rapidly growing force that consisted of British Regulars -- soldiers in the "regular" professional army -- from England and Scotland as well as provincial troops from Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware. This army's goal was to capture Fort Duquesne, at the forks of the Ohio River, the French post that had been a thorn in the side of the British for four years.

The march was slow and arduous. North Carolina's soliders built roads and forts in the wilderness and constantly prepared for attacks by Indians and French soliders. By the fall they were brigaded with the Virginia and Maryland troops, under the command of Colonel George Washington. In October, they successfully repulsed a French and Indian attack on the army's advance post.

By November the French at Fort Duquesne decided that the British were moving too slowly to make a major attack, and they dismissed much of their force. But the British kept marching. Some of the first troops to reach Fort Duquesne were North Carolinians. The French commander, realizing that he was outnumbered and could not defend the fort, burned it to the ground. The site of the fort was renamed Pittsburgh, in honour of William Pitt, the British Secretary of State whose planning and support for the war had made success possible.

The Cherokee War

By the time the troops returned to Carolina, relations with the Cherokee had deteriorated, and Fort Dobbs was put front and center in the developing Cherokee War. The Cherokee had begun the war as allies of the British, but did not trust either side. Many settlers similarly did not trust Indians of any nation. The Cherokee believed their efforts were unappreciated, and skirmishes broke out between frontier settlers and the Cherokee. In 1759, the Cherokee declared war on the British -- not as allies of France, but as an independent party.

Cherokee raids struck up and down the frontier, and it was reported that "the back Settlers had... mostly quitted their habitations, and taken shelter in Fort Dobbs." With a large force of Indians reportedly on the way, Major Waddell was sent from the coast to Fort Dobbs with more troops and some light artillery.

In February 1760, the Cherokee attacked Fort Dobbs. Waddell and nine other men marched 300 yards out of the fort and were attacked by 60 to 70 Cherokee. Waddell's men fired back and were able to retreat to the fort. Three soliders in the fort were wounded and one boy was killed.

The following year Fort Dobbs was to be the rendezvous point for five companies of provincials ordered to link up with Virginia troops and march against the Cherokee. By the time the 400 North Carolina troops joined the Virginians, though, the Cherokee were suing for peace. North Carolina's war was over.

The war ends

The war officially ended in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. Arthur Dobbs had predicted in 1756 that "when this war is over our frontier will be extended beyond the mountains" and said that the fort that bore his name was "only occasional at present." He was correct. Fort Dobbs fulfilled its varied functions during its six years of active service. With the threats from the French, their Indian allies, and the Cherokee eliminated, white settlement could continue to spread westward toward the mountains. The frontier quickly passed Fort Dobbs by, and it was no longer needed as a military post.

- 1. Minutes of the Upper House of the North Carolina General Assembly, December 18, 1754.

- 2. Letter from Arthur Dobbs to the Board of Trade of Great Britain, August 24, 1755.

- 3. Minutes of the Lower House of the North Carolina General Assembly, May 20, 1752.

- 4. Minutes of the Lower House of the North Carolina General Assembly, May 3, 1758.