The following passage is excerpted from W. E. B. Du Bois's "The Upbuilding of Black Durham: The Success of the Negroes and their Value to a Tolerant and Helpful Southern City" (1912). Durham was a historically important city for Black North Carolinians, as Du Bois wrote.

Durham, N. C., is a place which the world instinctively associates with tobacco. It has, however, other claims to notice, not only as the scene of Johnston's surrender at the end of the Civil War but particularly today as the seat of Trinity College, a notable institution.

It is, however, because of another aspect of its life that this article is written: namely, its solution of the race problem. There is in this small city a group of five thousand or more colored people, whose social and economic development is perhaps more striking than that of any similar group in the nation.

The Negroes of Durham County pay taxes on about a half million dollars' worth of property or an average of nearly $500 a family, and this property has more than doubled in value in the last ten years....

In all colored groups one may notice something of this coöperation in church, school, and grocery store. But in Durham, the development has surpassed most other groups and become of economic importance to the whole town.

There are, for instance, among the colored people of the town fifteen grocery stores, eight barber shops, seven meat and fish dealers, two drug stores, a shoe store, a haberdashery, and an undertaking establishment. These stores carry stocks averaging (save in the case of the smaller groceries) from $2,000 to $8,000 in value.

This differs only in degree from a number of towns; but black Durham has in addition to this developed five manufacturing establishments which turn out mattresses, hosiery, brick, iron articles, and dressed lumberDressed lumber has been sawn and given a smooth surface to be ready for building.. These enterprises represent an investment of more than $50,000. Beyond this the colored people have a number of financial enterprises among which are a building and loan association, a real estate company, a bank, and three industrial insurance companies.

The coöperative bonds of the group are completed in social lines by a couple of dozen professional men, twenty school teachers, and twenty churches....

The first thing I saw in black Durham was its new training schoolDr. James E. Shepard founded the National Religious Training School and Chautauqua in 1909. In the 1920s, with the school in financial trouble, Shepard persuaded the General Assembly that the state should take over the school. It became the North Carolina College for Negroes in 1925, the first state-supported college for African-American students in the nation. In 1969, the college became North Carolina Central University, and in 1972 it became part of the newly consolidated University of North Carolina. -- four neat white buildings suddenly set on the sides of a ravine, where a summer Chautauqua for colored teachers was being held. The whole thing had been built in four months by colored contractors after plans made by a colored architect, out of lumber from the colored planing mill and ironwork largely from the colored foundry. Those of its two hundred and fifty students who boarded at the school, slept on mattresses from the colored factory and listened to colored instructors from New York, Florida, Georgia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and North Carolina. All this was the partially realized dream of one colored man, James E. Shepard. He formerly worked as secretary for a great Christian organization, but dissatisfied at a peculiarly un-Christian drawing of the color line, he determined to erect at Durham a kind of training school for ministers and social workers which would be "different."

One morning there came out to the school a sharp-eyed brown man of thirty, C. C. Spaulding, who manages the largest Negro industrial insurance company in the world. At his own expense he took the whole school to town in carriages to "show them what colored people were doing in Durham."

Naturally he took them first to the home of his company -- "The North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association," an institution which is now twelve years old. One has a right to view industrial insurance with some suspicion and the Insurance Commissioner of South Carolina made last year a fifteen days thorough examination of this enterprise. Then he wrote: "I can not but feel that if all other companies are put on the same basis as yours, that it will mean a great deal to industrial insurance in North and South Carolina, and especially a great benefit to the Negro race."

The company's business has increased from less than a thousand dollars in 1899 to an income of a quarter of a million in 1910. It has 200,000 members, has paid a half million dollars in benefits, and owns its office buildings in three cities....

The Durham office building of this company is neat and light. Down stairs in the rented portion we visited the men's furnishing store which seemed a business-like establishment and carried a considerable stock of goods. The shoe store was newer and looked more experimental; the drug store was small and pretty.

From here we went to the hosiery mill and the planing mill. The hosiery mill was to me of singular interest. Three years ago I met the manager, C. C. Amey. He was then teaching school, but he had much unsatisfied mechanical genius. The white hosiery mills in Durham were succeeding and one of them employed colored hands. Amey asked for permission here to learn to manage the intricate machines, but was refused. Finally, however, the manufacturers of the machines told him that they would teach him if he came to Philadelphia. He went and learned. A company was formed and thirteen knitting and ribbing machines at seventy dollars apiece were installed, with a capacity of sixty dozen men's socks a day. At present the sales are rapid and satisfactory, and already machines are ordered to double the present output; a dyeing department and factory building are planned for the near future.

The brick yard and planing mill are part of the general economic organization of the town. R. B. Fitzgerald, a Northern-born Negro, has long furnished brick for a large portion of the state and can turn out 30,000 bricks a day.

To finance these Negro businesses, which are said to handle a million and a half dollars a year, a small banking institution has been started. The "Mechanics' and Farmers' Bank" looks small and experimental and owes its existence to rather lenient banking laws. It has a paid-in capital of $11,000 and it has $17,000 deposited by 500 different persons....

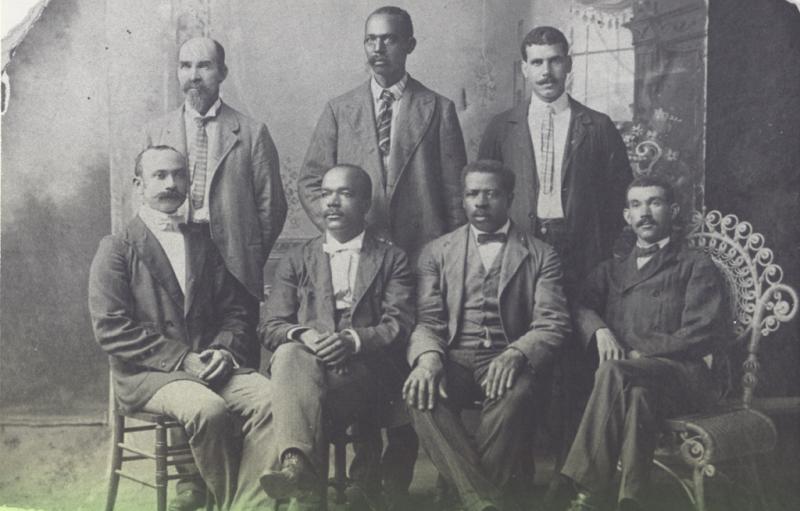

Three men began the economic building of black Durham: a minister with college training, a physican with professional training, and a barber who saved his money. These three called to their aid a bright hustling young graduate of the public schools, and with these four, representing vision, knowledge, thrift, and efficiency, the development began. The college man planned the insurance society, but it took the young hustler to put it through. The barber put his savings into the young business man's hands, the physician gave his time and general intelligence. Others were drawn in -- the brickmaker, several teachers, a few college-bred men, and a number of mechanics. As the group began to make money, it expanded and reached out. None of the men are rich -- the richest has an income of about $25,000 a year from business investments and eighty tenements; the others of the inner group are making from $5,000 to $15,000 -- a very modest reward as such rewards go in America.

Quite a number of the colored people have built themselves pretty and well-equipped homes -- perhaps fourteen of these homes cost from $2,500 to $10,000; they are rebuilding their churches on a scale almost luxurious, and they are deeply interested in their new training school. There is no evidence of luxury -- a horse and carriage, and the sending of children off to school is almost the only sign of more than ordinary expenditure.

If, now, we were considering a single group, geographically isolated, this story might end here. But never forget that Durham is in the South and that around these 5,000 Negroes are twice as many whites who own most of the property, dominate the political life exclusively, and form the main current of social life. What now has been the attitude of these people toward the Negroes? In the case of a notable few it has been sincerely sympathetic and helpful, and in the case of a majority of the whites it has not been hostile. Of the two attitudes, great as has undoubtedly been the value of the active friendship of the Duke family, General Julian S. Carr, and others, I consider the greatest factor in Durham's development to have been the disposition of the mass of ordinary white citizens of Durham to say: "Hands off -- give them a chance -- don't interfere."