Before the United States entered World War II, several companies already had contracts with the government to produce war equipment for the Allies. Almost overnight the United States entered the war and war production had to increase dramatically in a short amount of time. Auto factories were converted to build airplanes, shipyards were expanded, and new factories were built, and all these facilities needed workers. At first companies did not think that there would be a labor shortage so they did not take the idea of hiring women seriously. Eventually, women were needed because companies were signing large, lucrative contracts with the government just as all the men were leaving for the service.

Working was not new to women. Women have always worked, especially minority and lower-class women. However, the cultural division of labor by sex ideally placed white middle-class women in the home and men in the workforce. Also, because of high unemployment during the Depression, most people were against women working because they saw it as women taking jobs from unemployed men.

The start of World War II tested these ideas. Everyone agreed that workers were greatly needed. They also agreed that having women work in the war industries would only be temporary.

The United States government had to overcome these challenges in order to recruit women to the workforce. Early in the war, the government was not satisfied with women's response to the call to work.

The government decided to launch a propaganda campaign to sell the importance of the war effort and to lure women into working.

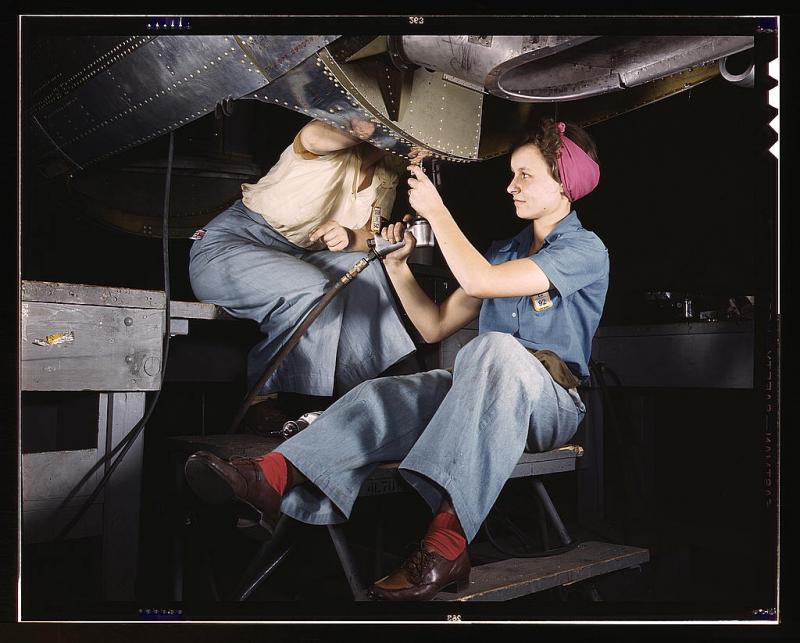

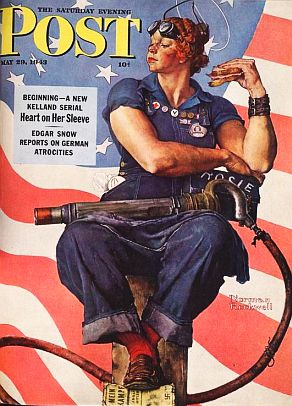

They promoted the fictional character of "Rosie the Riveter" as the ideal woman worker: loyal, efficient, patriotic, and pretty. A song, "Rosie the Riveter", became very popular in 1942. Norman Rockwell's image on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post on May 29, 1943 was the first widely publicized pictorial representation of the new "Rosie the Riveter". This led to many other "Rosie" images and women to represent that image. For example, the media found Rose Hicker of Eastern Aircraft Company in Tarrytown, New York and pictured her with her partner as they drove in a record number of rivets into the wing of a Grumman "Avenger" Bomber on June 8, 1943. Rose was an instant media success. In many other locations and situations around the country, "Rosies" were found and used in the propaganda effort. A few months after Rockwell's image, the most famous image of Rosie appeared in the government-commissioned poster "We Can Do It."

Women responded to the call to work differently depending on age, race, class, marital status, and number of children. Half of the women who took war jobs were minority and lower-class women who were already in the workforce. They switched from lower-paying traditionally female jobs to higher-paying factory jobs. But even more women were needed, so companies recruited women just graduating from high school. Eventually it became evident that married women were needed even though no one wanted them to work, especially if they had young children. It was hard to recruit married women because even if they wanted to work, many of their husbands did not want them to. Initially, women with children under 14 were encouraged to stay home to care for their families. The government feared that a rise in working mothers would lead to a rise in juvenile delinquency. Eventually, the demands of the labor market were so severe that even women with children under 6 years old took jobs.

While patriotism did influence women, ultimately it was the economic incentives that convinced them to work. Once at work, they discovered the nonmaterial benefits of working like learning new skills, contributing to the public good, and proving themselves in jobs once thought of as only men's work.

When the United States entered the war, 12 million women (one quarter of the workforce) were already working and by the end of the war, the number was up to 18 million (one third of the workforce). While ultimately 3 million women worked in war plants, the majority of women who worked during World War II worked in traditionally female occupations, like the service sector. The number of women in skilled jobs was actually few. Most women worked in tedious and poorly paid jobs in order to free men to take better paying jobs or to join the service. The only area that there was a true mixing of the sexes was in semiskilled and unskilled blue-collar work in factories. Traditionally female clerical positions were able to maintain their numbers and recruit new women. These jobs were attractive because the hours were shorter, were white-collar, had better job security, had competitive wages, and were less physically strenuous and dirty. The demand for clerical workers was so great that it exceeded the supply.

Like men, women would quit their jobs if they were unhappy with their pay, location, or environment. Unlike men, women suffered from the "double shift" of work and caring for the family and home. During the war, working mothers had childcare problems and the public sometimes blamed them for the rise in juvenile delinquency. In reality, though, 90% of mothers were home at any given time. The majority of women thought that they could best serve the war effort by staying at home. During the war, the average family on the homefront had a housewife and a working husband.

Some women enjoyed working, but others could not accept the inconveniences it caused. Most women saved the money they earned. Between the wartime shortages and long working hours, there was not much to spend money on anyway. Women workers were frequently reminded to buy war bonds. After the war, the money was used to buy houses and luxuries that had been unavailable during and before the war.

When women started working at traditionally male jobs the biggest problem was changing men's attitudes. Male employees and male-controlled unions were suspicious of women. Companies saw women's needs and desires on the job as secondary to men's, so they were not taken seriously or given much attention. In addition, employers denied women positions of power excluding them from the decision-making process of the company. Women wanted to be treated like the male workers and not given special consideration just because they were women.

As time went on and more and more women entered the work force, the attitudes towards women workers changed. Employers praised them.

While the image of the woman worker was important during the war, the prewar image of women as wives and mothers by no means disappeared. Mainstream society accepted temporary changes brought about by a war, but considered them undesirable on a permanent basis. The public reminded women that their greatest asset was their ability to take care of their homes and that career women would not find a husband.

After the war, the cultural division of labor by sex reasserted itself. Many women remained in the workforce but employers forced them back into lower-paying female jobs. Most women were laid off and told to go back to their homes.

During World War II there was a change in the image of women, but it was only superficial and temporary. The reality was that most women returned to being homemakers during the prosperity of the 1950s. However, the road taken by women in the work force during World War II continued into the future. Society had changed. The daughters and granddaughters of Rosies continued on the road blazed by their mothers and grandmothers.