The British won vast territory in North America after the Seven Years' War, but with that territory came the problem of governing it. British officials tried -- and failed -- to balance the interests of colonists and American Indians, and the conflicts that resulted made the colonists increasingly unhappy with British rule and led, ultimately, to the American Revolution.

Claims on western land

The Treaty of Paris of 1763 that ended the Seven Years' War gave Great Britain control of Canada and the entire present-day United States east of the Mississippi. When the war ended, Anglo-American colonists began to pour over the Appalachian Mountains in search of land. Many of these settlers had no official claim to the land -- the Indians who lived there hadn't ceded it, and in many cases, the land was claimed by private land companies. Wealthy Virginians, in particular, had invested heavily in these companies. Virginia claimed the entire Ohio valley as its territory, and the colonial government granted land west of the Appalachians to companies that speculated in the land -- bought it in hopes of making great profits by selling it to settlers a few years later. Many of the men who controlled Virginia's government, though, had invested in these same companies, and they naturally had reason to want the British to ease tensions in the west.

White settlement west of the Appalachians also created tension and conflict between settlers and American Indians. British military officials attempted to stop settlement, but eager settlers and land speculators ignored them, and the military wasn't willing to forcibly remove settlers from the lands they had claimed.

British officials made the situation worse by alienating American Indians who had been allied with France during the Seven Years' War. The French government had spent a great deal of money on gifts to their Indian allies. Gifts were a standard part of Indian diplomacy, a way to open discussions on a friendly and equal basis. When British forces arrived to take over former French forts, though, they stopped the practice of gift-giving, unwittingly antagonizing Indian leaders.

The Proclamation of 1763

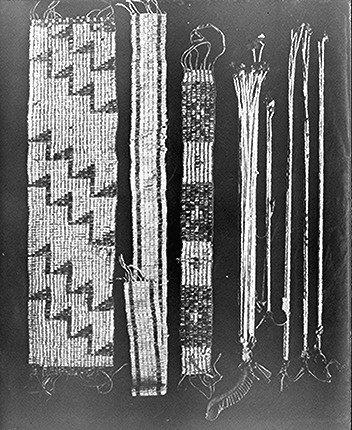

In response to British actions and western settlement, the leader of the Ottawa tribe, Pontiac, supported by other tribal leaders, sent messages encoded in wampum belts to other communities throughout the present-day Midwest to coordinate an attack on British forts. British forces didn't realize how deep Indian resentment ran, and the attack caught them by surprise. In the war the British called "Pontiac's Rebellion," they lost all their western forts except for Fort Pitt and Detroit, where British military officials had been tipped off about the attack.

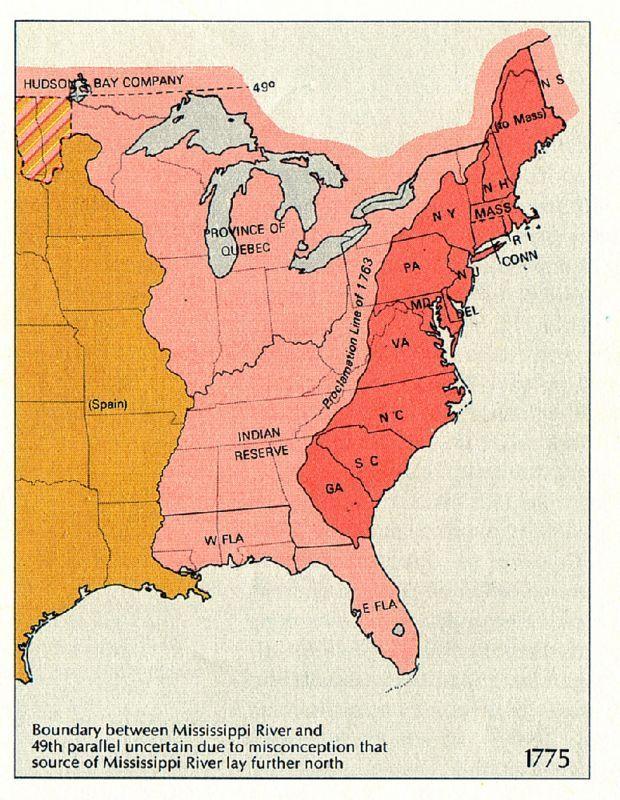

When news of the rebellion reached London, the government decided to reserve western lands for Indians. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 banned settlement beyond the line of the Appalachian Mountains. Land west of the Appalachians and south of the Ohio River -- including all of present-day Kentucky and Tennessee -- became an Indian reserve. The act also created the provinces of Quebec, West Florida, and East Florida. But there was no means of enforcing the proclamation, and it didn't stop settlement. It only angered settlers and the political elite who had speculated in western land.

The Quebec Act

A treaty with Pontiac did not end British troubles in the west, and the Proclamation of 1763 was not the last time the British government would alienate white settlers and speculators. In 1774, Parliament passed the Quebec Act, which was intended to keep French Canadians happy by restoring French civil law and allowing Catholics to hold office. It also brought Quebec under direct control of the king and extended Quebec's borders south to the Ohio River.

The Quebec Act angered the Virginia elite, since most of the western lands they claimed were now officially part of Quebec or in the Indian reserve. And Parliament had passed this act at the same time that Massachusetts' charter was revoked, when tensions between Britain and the colonies were escalating. Calvinist New Englanders saw the Quebec Act as promoting not only Catholicism, which they detested, but also autocratic power -- absolute power in the hands of the king. They saw the act as part of a British conspiracy to destroy colonists' freedom.

Toward the Revolution

When the American Revolution began, tensions between settlers and Indians became a part of the conflict. The Continental Congress' attempts to make alliances with Indians mostly failed, for most Indians saw the British military as the lesser of two evils in their struggle against settlers' encroachments on their land. Only the Oneida and Tuscarora Nations of the Iroquois confederacy sided with the colonists.

The ultimate effect of British frontier policy was to unite frontiersmen, Virginia land speculators, and New Englanders against unpopular British policies. These groups forged alliances with other colonists angered by British taxation, and together they resisted British rule -- and would eventually declare their independence.