The reign of Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603) was one of the high-water marks of English history. After the troubled years under her sister Mary I — known as "Bloody Mary" for her religious persecutions — the English welcomed the spirited, intelligent, and strong-willed Elizabeth. England had long been a small, somewhat static nation, coveted by the European powers and castigated by the Pope as a hotbed of Protestantism. Now there was a sense of possibilities, of national purpose, under the young queen.

The Tudors and English Protestantism

The Protestant Reformation was a movement in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by which many people and countries gradually broke away from the Catholic Church, which in the Middle Ages had been Western Europe's only church. Most people think of the Reformation as beginning with Martin Luther's 95 Theses -- criticisms of the Catholic Church -- in 1517, although discontentment with the church had been growing for several decades.

The Catholic Church resisted attempts by reformers to set up their own churches, and Catholic kings fought wars against countries that converted to Protestantism. These battles culminated in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). In England, conflict between Protestants and Catholics led to civil war in the seventeenth century.

At the end of the Middle Ages, England was a small nation on the fringe of Europe. In the 1400s, England had fought a long war with France, called the Hundred Years War. Its economy was poor, many people were hungry, and the "Black Death" -- repeated epidemics of the bubonic plague -- killed millions in the century after it arrived in the 1340s.

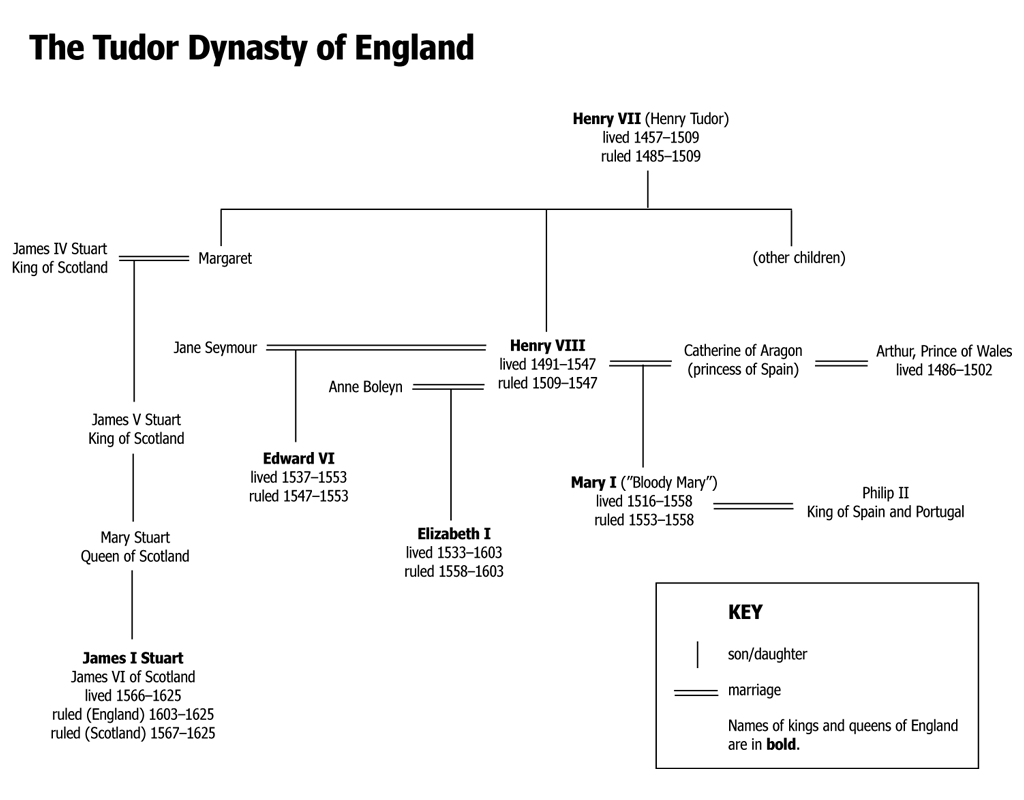

In the midst of this turmoil, the authority of the English kings was fading. Two competing houses -- families with claims to the throne -- fought a civil war, called the War of the Roses. Henry Tudor emerged from the War of the Roses as king, and as Henry VII, he worked to restore peace and prosperity and to strengthen the power of the throne. He also tried to forge an alliance with Spain by marrying his son, Arthur, to Catherine of Aragon, the daughter of the Spanish King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

Arthur died young, and Henry VII's second son succeeded him as Henry VIII. When Henry VIII became king in 1509, he married his brother's widow Catherine. But Henry and Catherine had only one child in eighteen years of marriage -- a daughter, Mary. Henry needed a son to succeed him as king, and he blamed Catherine for the lack of an heir. In 1533, he had the Archbishop of Canterbury -- the highest authority of the Catholic Church in England -- declare his marriage to Catherine invalid, and married Anne Boleyn.

The Pope responded by excommunicating Henry -- banishing him from the Catholic Church. At this time, Catholicism was the religion of nearly all of Western Europe -- not just the official religion but the only religion permitted. The Protestant Reformation had barely begun; it had taken root only in a few small areas where a ruler supported it. Elsewhere, the Catholic Church reigned supreme, and the Pope's word was law. Excommunication meant that Henry VIII was no longer a legitimate ruler.

Henry VIII, though, was not inclined to take anyone else's word as law. He separated England from the Catholic Church and created the Church of England. The Church of England had the same structure as the old Catholic Church, but instead of the Pope at its head, it had the king of England -- Henry himself.

By declaring England a Protestant nation and by annulling his marriage to Catherine, Henry made England and Catholic Spain enemies and set the stage for religious conflict within England that would last until the late 1600s. His daughter Mary, who like her Spanish mother was Catholic, took the throne in 1553 as Queen Mary I, and she married Prince Philip of Spain. Again, England was launched into bloody civil war and a period of religious oppression. At this time Europeans assumed that a nation would be one religion or another, and the English fought one another over whether England would be Catholic or Protestant.

The Golden Age

In 1559 Mary died, and because she had no children, her half-sister Elizabeth -- daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn -- succeeded her. Elizabeth affirmed England's Protestantism and set up a conflict with Spain. But she reestablished the authority of the crown and led England into an era of peace and prosperity that some historians call the "Golden Age" of England.

Elizabeth's radiant dress, sparkling court, and adroit advisors set the tone for the period, and her personality helped give the nation a strong self-image: dynamic yet stable, where ventures and reputations rose and fell with dizzying speed while the machinery of government ground on. Hers was a rule of benevolent authoritarianism, and her shrewd and sensitive handling of people earned total loyalty from her advisors and early compliance from Parliament. She felt no need for a standing army in the "French fashion." The aristocracy's grand homes changed from fortified castles to open manors, reflecting their owners' confidence in the stable social order and in the state's ability to defend them. That strength also benefited the common people, who took pride in England's growing international prestige and enjoyed an improved standard of living. Elizabeth's reluctance to indulge in petty wars and her shrewd financial management kept the Crown on a sound financial footing for most of her rule. The old feudal system had faded, and the economy was opening up, with a new middle class of merchants searching for investments and expanded markets for the products of England.

So with new strength and self-confidence, England turned outward, and began to make the sea its own. The nation finally had the means and the will to challenge Spain's and Portugal's dominance of world exploration and exploitation. To that end "privateers" served an important function. Their private fleets were supposed to raid only the shipping of official enemies, but during the cold war with France and Spain, the ships of both countries were fair game.

Sir Francis Drake's circumnavigation of the world (1577-1580) was also the most famous English privateering voyage. He looted Spanish shipping and, by flouting Spain's claims to monopoly in the Americas, proved the weakness of its empire.

Successful sea captains weren't the only ones to find Elizabeth's favor. Under her rule, England enjoyed a flowering of the arts, especially literature. During her reign, William Shakespeare gained renown for his plays and sonnets; Francis Bacon wrote important essays promoting science and progress; Edmund Spenser wrote his epic poem The Fairie Queene about Queen Elizabeth; and Philip Sidney became famous for his poetry. Their names commanded as much respect as those of explorers and soldiers such as Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake.

England and Spain

In the 1580s, Protestant England's rivalry with Catholic Spain flared into open war. King Philip II of Spain -- who had been married to Elizabeth's sister Queen Mary -- wanted to stop England's harassment of Spain's colonial possessions and fleets and to prevent England from threatening Spanish power on the continent of Europe. In 1588, he sent a fleet of ships to invade England. That fleet has become known as the Spanish Armada, and it is famous mainly for being an utter disaster for Spain.

In May 1588, 130 ships carrying 25,000 men left Spain for the Spanish Netherlands (now Belgium and Holland), where they were to pick up an additional army of 30,000. But bad weather blew the armada off course, and English ships prevented them from reaching port. On August 8, the English fleet defeated the Spanish in battle and forced the armada up the coast of Scotland, where it had to sail all the way around Britain before returning home. Only half the men and ships of the original armada returned safely to Spain.

The defeat of the armada kept the Spanish army out of Britain, but it was not a resounding victory for England. The war between England and Spain continued until the end of Elizabeth's reign, when her successor James I signed a peace treaty with Philip III. It prevented England from fully supporting its first American colony at Roanoke and delayed further attempts at colonization until 1607. The war cost both nations greatly, and Spain won most of its remaining battles. But the reign of Elizabeth I marked a turning point in European history. By the end of the seventeenth century, Spanish power was in decline, and England's had begun to rise.