Although most black people in the United States converted to Christianity by the early nineteenth century, they interpreted Christianity very differently from the way white people had intended. The Bible includes stories of societies in which slavery was common, and there are many stories with lessons about the importance of obedience. Enslavers and white preachers quoted these passages to enslaved people in hopes of convincing them to accept their place in southern society. In addition, white southerners sympathetic to slavery used the occurrence of slavery in the Bible — and the fact that Jesus never spoke out against it — to justify slavery to themselves.

Enslaved people, though, read the Bible differently. When Jesus said that all are equally loved by God, they took that as condemnation enough of slavery. In the story of Moses, who led the Hebrew people out of slavery in Egypt to freedom in the "promised land," enslaved black people found hope that they would one day find their own promised land. And in the plagues God sent upon Egypt they saw a warning to nineteenth-century enslavers that they, too, would be made to pay for their sins.

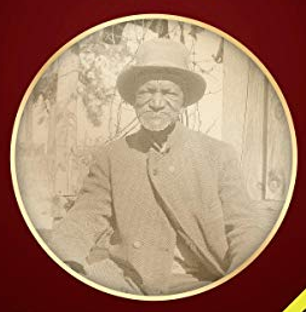

John Jea was born in West Africa in 1773, near Calabar in the Bight of Biafra. He was enslaved at the age of two, and brought to New York by enslavers. (The colony and later the state of New York allowed slavery until 1827.) In his autobiography or "narrative" of his life, written about 1811, Jea tells of his conversion to Christianity. After being baptized, he was freed and became a preacher.

In this excerpt, from the beginning of his narrative, Jea tells about the conditions on his first enslaver's farm. He also describes the way both his enslaver and the white minister used Christianity to preach obedience to enslaved people and to convince them of their worthlessness.

I, John, Jea, the subject of this narrative, was born in the town of Old Callabar, in Africa Calabar is in present-day Nigeria. Since the sixteenth century, it had been an international trading sea port, and it served as an important hub in the trans-Atlantic African slave trade., in the year 1773. My father's name was Hambleton Robert Jea, my mother's name Margaret JeaThese would have been their American names, not the names they had when they lived in Africa. When African slaves arrived in the Americas they were assigned new names either by the people who sold them or by their new master.; they were of poor, but industrious parents. At two years and a half old, I and my father, mother, brothers, and sisters, were stolen, and conveyed to North America, and sold for slaves; we were then sent to New YorkAt this time, New York state had the largest slave population of any state north of Maryland. In 1799 New York passed a gradual emancipation law, freeing any African-American born into slavery after that date, and the state eventually abolished slavery in 1827., the man who purchased us was very cruel, and used us in a manner, almost too shocking to relate; my master and mistress's names were Oliver and Angelika Triebuen, they had seven children -- three sons and four daughters; he gave us a very little food or raiment, scarcely enough to satisfy us in any measure whatever; our food was what is called Indian corn pounded or bruised and boiled with water, the same way burgo Burgoo is a very thick oatmeal or porridge. is made, and about a quart of sour butter-milk poured on it; for one person two quarts of this mixture, and about three ounces of dark bread, per day, the bread was darker than that usually allowed to convicts, and greased over with very indifferent hog's lard; at other times when he was better pleased, he would allow us about half-a-pound of beef for a week, and about half-a-gallon of potatoes; but that was very seldom the case, and yet we esteemed ourselves better used than many of our neighbours.

Our labour was extremely hard, being obliged to work in the summer from about two o'clock in the morning, till about ten or eleven o'clock at nightThis means the slaves slept two or three hours a night in the summer and three or four hours a night in the winter. Certainly slaves worked long, hard hours, but does this seem plausible to you, or do you think he is exaggerating? Are there other parts of the story in which you think he might be exaggerating? Why might he exaggerate to make his point? If he is exaggerating, does that make you take him less seriously, or is his overall point still valid?, and in the winter from four in the morning, till ten at night. The horses usually rested about five hours in the day, while we were at work; thus did the beasts enjoy greater privileges than we did. We dared not murmur, for if we did we were corrected with a weapon an inch and-a-half thick, and that without mercy, striking us in the most tender parts, and if we complained of this usage, they then took four large poles, placed them in the ground, tied us up to them, and flogged us in a manner too dreadful to behold; and when taken down, if we offered to lift up our hand or foot against our master or mistress, they used us in a most cruel manner; and often they treated the slaves in such a manner as caused their deathIn many states, it was legal for a slaveholder to kill his own slave. Some people argued that there was no need for this to be a crime, since no one would willingly kill his own slave -- a slave was property, an investment, and if a master killed his own slave, he would lose money. In reality, although outright violent murder was not common, many slaves died from beatings, starvation, overwork, disease, and neglect., shooting them with a gun, or beating their brains out with some weapon, in order to appease their wrath, and thought no more of it than if they had been brutes: this was the general treatment which slaves experienced. After our master had been treating us in this cruel manner, we were obliged to thank him for the punishment he had been inflicting on us, quoting that Scripture which saith, "Bless the rod, and him that hath appointed it." But, though he was a professor of religion, he forgot that passage which saith "God is love, and whoso dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him."Both quotations are from the Bible. The first is from Micah 6:9, in the Old Testament: The Lord's voice crieth unto the city, and the man of wisdom shall see thy name: hear ye the rod, and who hath appointed it. The second is 1 John 4:16, in the New Testament: God is love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him. And, again, we are commanded to love our enemiesIn Luke 6:27, Jesus is quoted as saying, "But I say unto you which hear, Love your enemies, do good to them which hate you.", but it appeared evident that his wretched heart was hardened; which led us to look up unto him as our godBecause Jea's master appeared to the slaves to be all-powerful and showed no mercy -- his heart was "hardened" -- he in effect substituted himself for God. Jea means this as a spiritual condemnation of his slave master. The first of the Ten Commandments were "Thou shalt have no other Gods before me.", for we did not know him who is able to deliver and save all who call upon him in truth and sincerity. Conscience, that faithful monitor, (which either excuses or accuses) caused us to groan, cry, and sigh, in a manner which cannot be uttered.

We were often led away with the idea that our masters were our gods; and at other times we placed our ideas on the sun, moon, and stars, looking unto them, as if they could save us; at length we found, to our great disappointment, that these were nothing else but the works of the Supreme Being; this caused me to wonder how my master frequently expressed that all his houses, land, cattle, servants, and every thing which he possessed was his own; not considering that it was the Lord of Hosts, who has said that the gold and the silver, the earth, and the fullness thereof, belong to himThis is a reference to Pslams 24:1: "The earth is the Lord's, and the fulness thereof; the world, and they that dwell therein.".

Our master told us, that when we died, we should be like the beasts that perish; not informing us of God, heaven, or eternal punishments, and that God hath promised to bring the secrets of every heart into judgment, and to judge every man according to his works....