For nearly a century, many states had managed to escape the obvious mandate of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Court decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education and the many others won by Thurgood Marshall and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People finally established that government, even state governments in the Deep South, could not discriminate against African Americans or anyone else. Civil rights activists like the Freedom Riders risked their lives, but at least there was no doubt that the law was on their side and that those who attacked them were lawbreakers.

But the owners of a movie theater or a department store lunch counter were not the government. As a result, the civil rights movement was obliged to wage battles one city and one business at a time. While Rosa Parks's brave refusal to move to the back of the bus led to the desegregation of public transportation in Montgomery, Alabama, hundreds or even thousands more Rosa Parks — and Martin Luther Kings — would be needed to desegregate fully the South.

Plainly, legislation was needed to prohibit acts of private discrimination in public places. Such a law would represent a dramatic expansion of federal authority. The American Constitution explains what the federal — and, in the post-Civil War amendments the state governments — may and may not do. It does not speak of Woolworth's lunch counter.

In the end, proponents of what became the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would assert, and the courts subsequently would accept, that Congress possessed the authority to ban discrimination in employment, public accommodations, and other aspects of life. They pointed to the constitutional provision (Article I, Section 8) authorizing Congress "to regulate Commerce… among the several States." By the mid-20th century, nearly every economic transaction involved some form of interstate commerce, were one to look closely enough. In 1969, for instance, the Supreme Court, in Daniel v. Paul, rejected a discriminatory "entertainment club's" claim that its lack of interstate activity exempted it from the Civil Rights Act. Among the Court's findings: The snack bar served hamburgers and hot dogs on rolls, and the "principal ingredients going into the bread were produced and processed in other States."

President Johnson's introduction of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provoked one of the nation's great political contests. The act prevailed because much of the nation had looked hard into Bull Connor's eyes and had not liked what it saw. But passage also would require all of Johnson's formidable skills. It was understood that majorities of Republicans and northern Democrats would support the bill, but that Johnson would have to engineer a two-thirds Senate majority to overcome the inevitable filibuster by southern Democrats.

Johnson, in his first State of the Union Address on January 8, 1964, urged Congress to "let this session... be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined." The months that followed saw intense congressional fact-finding and debate over the act. The House of Representatives held more than 70 days of public hearings, during which some 275 witnesses offered nearly 6,000 pages of testimony. At the end of this process, the House passed the bill by a vote of 290 to 130.

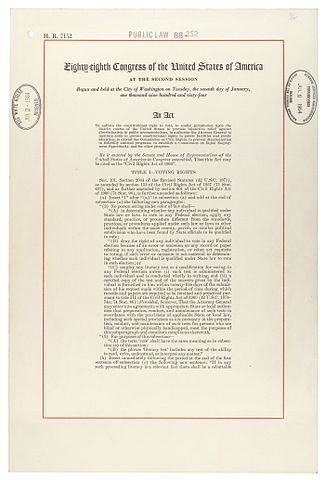

The Senate filibuster would last for 57 days, during which time the Senate conducted virtually no other business. As the speeches continued (one senator carried a 1,500-page speech onto the floor), President Johnson subjected many a senator to "The Treatment," and a variety of labor, religious, and civil rights groups lobbied for cloture and a final vote. Finally, on June 10, 1964, the Senate voted 71 to 29 to end debate — the first time cloture had ever been successfully invoked in a civil rights matter. A week later, the Senate passed its version of the civil rights bill. On July 2, 1964, the House of Representatives agreed to the Senate version, sending the bill to the White House.

President Johnson affixed his signature that evening, in the course of a nationally televised address. "Americans of every race and color have died in battle to protect our freedom," he told the nation. He continued,

Americans of every race and color have worked to build a nation of widening opportunities. Now our generation of Americans has been called on to continue the unending search for justice within our own borders.

We believe that all men are created equal. Yet many are denied equal treatment.

We believe that all men have certain unalienable rights. Yet many Americans do not enjoy those rights.

We believe that all men are entitled to the blessings of liberty. Yet millions are being deprived of those blessings — not because of their own failures, but because of the color of their skin.

The reasons are deeply embedded in history and tradition and the nature of man. We can understand — without rancor or hatred — how this all happened.

But it cannot continue. Our Constitution, the foundation of our Republic, forbids it. … The purpose of the law is simple.

It does not restrict the freedom of any American, so long as he respects the rights of others.

It does not give special treatment to any citizen.

It does say the only limit to a man's hope for happiness, and for the future of his children, shall be his own ability.

It does say that there are those who are equal before God shall now also be equal in the polling booths, in the classrooms, in the factories...

My fellow citizens, we have come now to a time of testing. We must not fail.

Let us close the springs of racial poison. Let us pray for wise and understanding hearts. Let us lay aside irrelevant differences and make our nation whole. Let us hasten that day when our unmeasured strength and our unbounded spirit will be free.