In the early years of the republic, state governments often advised their representatives in the House of Representatives or Congress how to vote on issues of particular importance. One of these issues of particular importance was The Federal Judiciary Act of 1801, which was passed less than three weeks before the end of John Adam's presidency and a Federalist congressional majority. The act, known colloquially as the "Midnight Judges" Act, reduced the number of judges on the Federal Supreme Court, ended "circuit riding" by judges, created sixteen judgeships and six circuit court districts, and broadened the range of cases that would be heard in Federal Court rather than state courts. All in all, the act gave more power to the Federal Court system and was not well-received by members of the Democratic-Republican Party (Jeffersonian Republicans), who had won the presidential election as well as congressional majority during the election of 1799. Democratic-Republicans felt that a stronger federal judiciary lessened the power of state governments.

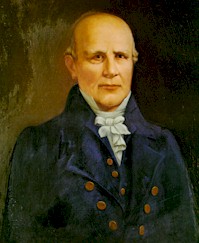

When North Carolina's General Assembly recommended that their representatives vote to repeal the Federal Judiciary Act of 1801, Representatives Archibald Henderson and John Stanly rejected the recommendation of their state legislature regarding judiciary issues, and debates between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans escalated. Below are excerpts from Representative Nathaniel Macon's February 1802 speech before the House of Representatives regarding the Repeal of the Judiciary Act.

Sir, I was astounded when my colleagueRepresentative Henderson, from Salisbury, had just made a speech laying out the Federalist point of view in favor of keeping the Judiciary Act. Henderson is the "colleague" to whom Macon refers in his own speech. In his speech, Henderson had predicted that if judges were no longer fully independent -- if a judge's position could be taken away by a legislature elected by the people -- then the American union would fall apart. "The wound you are about to give it will be mortal," he said; "it may languish out a miserable existence for a few years, but it will surely die. It will neither serve to protect its friends nor defend itself from the omnipotent energies of its enemies. Better at once to bury it will all our hopes." (Quoted in Dodd, The Life of Nathaniel Macon, p. 403.) It actually was not uncommon at this time for politicians to predict that their opponents' policies would break up the nation. So soon after the Revolution, America's political system was still unstable, and the national government had far less control over matters in the states than it does today. (Of course, exaggerated warnings of doom aren't hard to find in today's politics, either.) In a way, Macon and Henderson were still fighting the Revolution. Henderson insisted on a strong union to provide order and defend against external threats -- something that hadn't existed during the War for Independence, and which the Constitution was supposed to establish. Macon, meanwhile, reminded his colleagues that power comes from the people -- the principle for which the Revolution was fought and which was established in the opening words of the Constitution. said that the judges should hold their offices, whether useful or not, and that their independence was necessary, as he emphatically said, to protect the people against the worst enemies, themselvesNearly all Americans agreed that a "mixed" constitution was the best form of government -- something that would balance the desires of the majority while protecting the rights of the minority. But what was the best balance? Democratic-Republicans like Macon, remembering the abuses of King George III, feared allowing too much power to fall into too few hands. Federalists, meanwhile, remembered the mob violence of the Revolution -- and of the French Revolution in the 1790s -- and feared giving too much power to the people. This is what Macon's opponent meant by saying that the people were their own "worst enemies" -- that left unchecked by men of wealth and good judgement, the people cannot be trusted to act in their own best interests. Independent judges who could not be removed from office, thought the Federalists, would help to check or limit the people's misuse of their power.; their usefulness is the only true test of their necessity, and if there is no use for them they ought not to be continued. I will ask my colleague whether since the year 1783, he has heard any disorder in the State we represent, or whether any act has been done there which can warrant or justify such an opinion, that "it is necessary to have the judges to protect the people from their worst enemies, themselves." I had thought we, the people, formed this government, and might be trusted with it....

Another expression of his equally astonished me; he said that on the 7th day of December a spirit which had spread discord and destruction in other countries, made its entry into this House. What! are we to be told, because at the last election the people thought proper to change some of their representativesThe "last election" was the election of 1800, in which the Federalist President John Adams was replaced by the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson. The Democratic-Republicans also won majorities in Congress that year for the first time. It was essentially the first time in history that a national government had changed hands peacefully. Although most Americans accepted the change as proper workings of a republic, some Federalists bitterly resented their loss of power. and put out some of those who had heretofore been in power, and to put others in power of different opinions, that a destroying spirit entered into all the public functionaries? For what, sir, are elections held, if it be not that the people should change their representatives when they do not like them? And are we to be told from the house-tops that the only use of elections is to promote, not public good, but public mischief?...

Again he says if you repeal the law the rich will oppress the poor. Nothing but too much law can anywhere put in the power of the rich to oppress the poor. Suppose you had no law at all, could the rich oppress the poor? Could they get six, eight or ten per cent for money from the poor without law?Since Macon thought of himself as one of "the people" and not a rich man, and since he was a strong believer in democracy, this statement might surprise you. Today, people who want to protect the poor from the rich typically want more laws, not fewer. But Democratic-Republicans saw strong government as a tool of oppression. Small farmers in North Carolina still faced many of the difficulties the Regulators had faced thirty years earlier -- a lack of money, a lack of representation -- and men like Macon had not forgotten those earlier abuses of power. By keeping power in the hands of the many, he hoped to limit the power of government to oppress anyone, or to allow any one group to oppress another. In particular, Macon points out that the rich could not get interest on their loans ("six, eight or ten per cent for money") without the law to enforce payment of debts. If you destroy all law and government can the few oppress the many or will the many oppress the few? But the passing of the bill will neither put it in the power of the rich to oppress the poor, nor the poor to oppress the rich. There will then be law enough in the country to prevent the one from oppressing the other. But while the elective principle remains free, no great danger of lasting oppression, can be really apprehended; as long as this continues the people will know who to trust....

It is asked, will you abolish the mint, that splendid attribute of sovereignty? Yes, sir: I would abolish the mint; that splendid attribute of sovereignty, because it is only a splendid attribute of sovereignty, and nothing else; it is one of those splendid establishments which takes money from our pockets without being of any use to us. In the State that we represent I do not believe there are as many cents in circulation as there are counties. This splendid attribute of sovereignty has not made money more plenty; it has only made more places for spending moneyFederalists wanted the U.S. to be a strong, commercial nation, and believed the federal government should promote commerce. During Washington's administration, they had created a national mint to coin money and a national bank to loan money to businesses. Macon was unimpressed with the mint. Federalists saw it as a "splendid attribute of sovereignty" -- the sort of institution a proud, independent nation ought to have. But, Macon says here, it hadn't increased the supply of money available to poor farmers; it had only helped business -- making "more places for spending money." Interestingly, later in this speech, Macon referred to himself as "poor." No politician today would call himself poor, but politicians do typically insist that they are middle class, which has the same effect of putting themselves in the same boat with the voters. Federalists, by contrast, had more of a reputation for being wealthy and elitist.

Source Citation:

Dodd, William E. The Life of Nathaniel Macon. Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards & Broughton, 1903.