Intimations of terrorism

Near the close of his administration, George H. W. Bush sent American troops to the chaotic East African nation of Somalia. Their mission was to spearhead a U.N. force that would allow the regular movement of food to a starving population.

Somalia became yet another legacy for the Clinton administration. Efforts to establish a representative government there became a "nation-building" enterprise. In October 1993, American troops sent to arrest a recalcitrant warlord ran into unexpectedly strong resistance, losing an attack helicopter and suffering 18 deaths. The warlord was never arrested. Over the next several months, all American combat units were withdrawn.

From the standpoint of the administration, it seemed prudent enough simply to end a marginal, ill-advised commitment and concentrate on other priorities. It only became clear later that the Somalian warlord had been aided by a shadowy and emerging organization that would become known as al-Qaida, headed by a fundamentalist Muslim named Osama bin Laden. A fanatical enemy of Western civilization, bin Laden reportedly felt confirmed in his belief that Americans would not fight when attacked.

By then the United States had already experienced an attack by Muslim extremists. In February 1993, a huge car bomb was exploded in an underground parking garage beneath one of the twin towers of the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan. The blast killed seven people and injured nearly a thousand, but it failed to bring down the huge building with its thousands of workers. New York and federal authorities treated it as a criminal act, apprehended four of the plotters, and obtained life prison sentences for them. Subsequent plots to blow up traffic tunnels, public buildings, and even the United Nations were all discovered and dealt with in a similar fashion.

Possible foreign terrorism was nonetheless overshadowed by domestic terrorism, primarily the Oklahoma City bombing. The work of right-wing extremists Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, it killed 166 and injured hundreds, a far greater toll than the 1993 Trade Center attack. But on June 25, 1996, another huge bomb exploded at the Khobar Towers U.S. military housing complex in Saudi Arabia, killing 19 and wounding 515. A federal grand jury indicted 13 Saudis and one Lebanese man for the attack, but Saudi Arabia ruled out any extraditions.

Two years later, on August 7, 1998, powerful bombs exploding simultaneously destroyed U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 301 people and injuring more than 5,000. In retaliation Clinton ordered missile attacks on terrorist training camps run by bin Laden in Afghanistan, but they appear to have been deserted. He also ordered a missile strike to destroy a suspect chemical factory in Sudan, a country which earlier had given sanctuary to Bin Laden.

On October 12, 2000, suicide bombers rammed a speedboat into the U.S. Navy destroyer Cole, on a courtesy visit to Yemen. Heroic action by the crew kept the ship afloat, but 17 sailors were killed. Bin Laden had pretty clearly been behind the attacks in Saudi Arabia, Africa, and Yemen, but he was beyond reach unless the administration was prepared to invade Afghanistan to search for him.

The Clinton administration was never willing to take such a step. It even shrank from the possibility of assassinating him if others might be killed in the process. The attacks had been remote and widely separated. It was easy to accept them as unwelcome but inevitable costs associated with superpower status. Bin Laden remained a serious nuisance, but not a top priority for an administration that was nearing its end.

The presidential election of 2000 and the war on terror

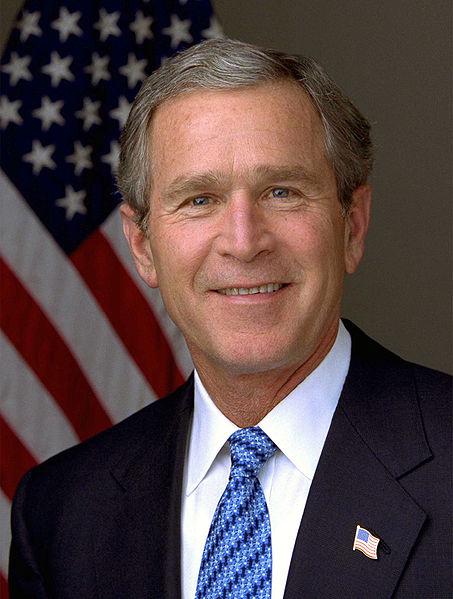

The Democratic Party nominated Vice President Al Gore to head their ticket in 2000. To oppose him the Republicans chose George W. Bush, the governor of Texas and son of former President George H. W. Bush.

Gore ran as a dedicated liberal, intensely concerned with damage to the environment and determined to seek more assistance for the less privileged sectors of American society. He seemed to place himself somewhat to the left of President Clinton.

Bush established a position closer to the heritage of Ronald Reagan than to that of his father. He displayed a special interest in education and called himself a "compassionate conservative." His embrace of evangelical Christianity, which he declared had changed his life after a misspent youth, was of particular note. It underscored an attachment to traditional cultural values that contrasted sharply with Gore's technocratic modernism. The old corporate gadfly Ralph Nader ran well to Gore's left as the candidate of the Green Party. Conservative Republican Patrick Buchanan mounted an independent candidacy.

The final vote was nearly evenly divided nationally; so were the electoral votes. The pivotal state was Florida; there, only a razor-thin margin separated the candidates and thousands of ballots were disputed. After a series of state and federal court challenges over the laws and procedures governing recounts, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a narrow decision that effectively gave the election to Bush. The Republicans maintained control of both houses of Congress by a small margin.

The final totals underscored the tightness of the election: Bush won 271 electoral votes to Gore's 266, but Gore led him in the national popular vote 48.4 percent to 47.9 percent. Nader polled 2.7 percent and Buchanan .4 percent. Gore, his states colored blue in media graphics, swept the Northeast and the West Coast; he also ran well in the Midwestern industrial heartland. Bush, whose states were colored red, rolled over his opponent in the South, the rest of the Midwest, and the mountain states. Commentators everywhere dwelled on the vast gap between "red" and "blue" America, a divide they characterized by cultural and social rather than economic differences, and all the more emotional for that reason. George Bush took office in a climate of extreme partisan bitterness.

Bush expected to be a president primarily concerned with domestic policy. He wanted to reform education. He had talked during his campaign about an overhaul of the social security system. He wanted to follow Reagan's example as a tax cutter.

The president quickly discovered that he had to deal with an economy that was beginning to slip back from its lofty peak of the late 1990s. This helped him secure passage of a tax cut in May 2001. At the end of the year, he also obtained the "No Child Left Behind" Act, which required public schools to test reading and mathematical proficiency on an annual basis; it prescribed penalties for those institutions unable to achieve a specified standard. Projected deficits in the social security trust fund remained unapressed.

The Bush presidency changed irrevocably on September 11, 2001, when the United States suffered the most devastating foreign attack ever against its mainland. That morning, Middle Eastern terrorists simultaneously hijacked four passenger airplanes and used two of them as suicide vehicles to destroy the twin towers of the World Trade Center. A third crashed into the Pentagon building, the Defense Department headquarters just outside of Washington, D.C. The fourth, probably meant for the U.S. Capitol, crashed into the Pennsylvania countryside as passengers fought the hijackers.

The death toll, most of it consisting of civilians at the World Trade Center, was approximately 3,000, exceeding that of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. The economic costs were also heavy. The destruction of the trade center took several other buildings with it and shut down the financial markets for several days. The effect was to prolong the already developing recession.

As the nation began to recover from the 9/11 attack, an unknown person or group sent out letters containing small amounts of anthrax bacteria. Some went to members of Congress and administration officials, others to obscure individuals. No notable person was infected. Five victims died, however, and several others suffered serious illness. The mailings touched off a wave of national hysteria, then stopped as supenly as they had begun, and remained a mystery.

It was in this setting that the administration obtained passage of the USA Patriot Act on October 26, 2001. Designed to fight domestic terrorism, the new law considerably broadened the search, seizure, and detention powers of the federal government. Its opponents argued that it amounted to a serious violation of constitutionally protected individual rights. Its backers responded that a country at war needed to protect itself.

After initial hesitation, the Bush administration also decided to support the establishment of a gigantic new Department of Homeland Security. Authorized in November 2002, and designed to coordinate the fight against domestic terrorist attack, the new department consolidated 22 federal agencies.

Overseas, the administration retaliated quickly against the perpetrators of the September 11 attacks. Determining that the attack had been an al-Qaida operation, it launched a military offensive against Osama bin Laden and the fundamentalist Muslim Taliban government of Afghanistan. The United States secured the passive cooperation of the Russian Federation, established relationships with the former Soviet republics that bordered Afghanistan, and, above all, resumed a long-neglected alliance with Pakistan, which provided political support and access to air bases.

Utilizing U.S. Army special forces and Central Intelligence Agency paramilitary operatives, the administration allied with long-marginalized Afghan rebels. Given effective air support, the coalition ousted the Afghan government in two months. Bin Laden, Taliban leaders, and many of their fighters were believed to have escaped into remote, semi-autonomous areas of northeastern Pakistan. From there they would try to regroup and attack the shaky new Afghan government.

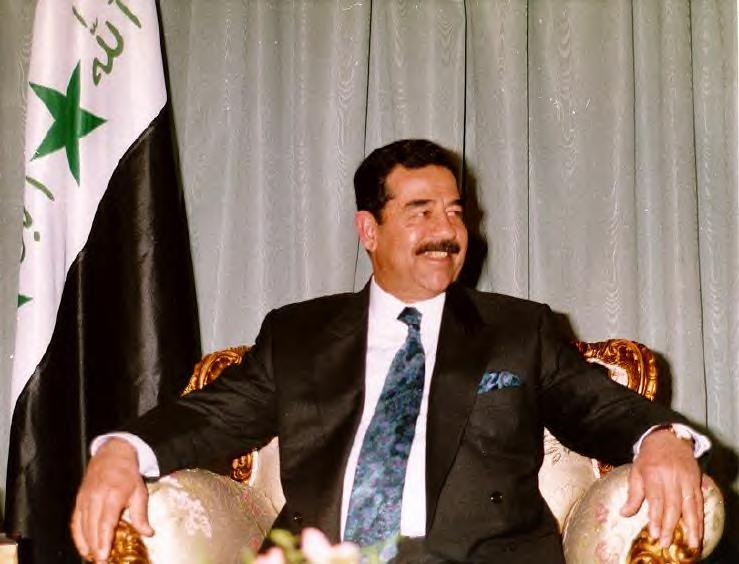

In the meantime, the Bush administration identified other sources of enemy terrorism. In his 2002 State of the Union apress, the president named an "axis of evil" that he thought threatened the nation: Iraq, Iran, and North Korea. Of these three, Iraq seemed to him and his advisers the most immediately troublesome. Saddam Hussein had successfully ejected U.N. weapons inspectors. The economic sanctions against Iraq were breaking down, and, although the regime was not believed to be involved in the 9/11 attacks, it had engaged in some contacts with al-Qaida. It was widely believed, not just in the United States but throughout the world, that Iraq had large stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons and might be working to acquire a nuclear capability. Why else throw out the inspection teams and endure continuing sanctions?

Throughout the year, the administration pressed for a U.N. resolution demanding resumption of weapons inspection with full and free access. In October 2002, Bush secured congressional authorization for the use of military force by a vote of 296-133 in the House and 77-23 in the Senate. The U.S. military began a buildup of personnel and material in Kuwait.

In November 2002, the U.N. Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1441 requiring Iraq to afford U.N. inspectors the unconditional right to search anywhere in Iraq for banned weapons. Five days later, Iraq declared it would comply. Nonetheless, the new inspections teams complained of bad faith. In January 2003, chief inspector Hans Blix presented a report to the United Nations declaring that Iraq had failed to account for its weapons of mass destruction, although he recommended more efforts before withdrawing.

Despite Saddam's unsatisfactory cooperation with the weapons inspectors, the American plans to remove him from power encountered unusually strong opposition in much of Europe. France, Russia, and Germany all opposed the use of force, making impossible the passage of a new Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force against Iraq. Even in those nations whose governments supported the United States, there was strong popular hostility to cooperation. Britain became the major U.S. ally in the war that followed; Australia and most of the newly independent Eastern European nations contributed assistance. The governments of Italy and Spain also lent their backing. Turkey, long a reliable American ally, declined to do so.

On March 19, 2003, American and British troops, supported by small contingents from several other countries, began an invasion of Iraq from the south. Small groups airlifted into the north coordinated with Kurdish militia. On both fronts, resistance was occasionally fierce but usually melted away. Baghdad fell on April 9. On April 14, Pentagon officials announced that the military campaign was over.

Taking Iraq turned out to be far easier than administering it. In the first days after the end of major combat, the country experienced pervasive looting. Hit-and-run attacks on allied troops followed and became increasingly organized, despite the capture of Saddam Hussein and the deaths of his two sons and heirs. Different Iraqi factions at times seemed on the verge of war with each other.

New weapons inspection teams were unable to find the expected stockpiles of chemical and biological weaponry. Although neither explanation made much sense, it increasingly seemed that Saddam Hussein had either engaged in a gigantic and puzzling bluff, or possibly that the weapons had been moved to another country.

After the fall of Baghdad, the United States and Britain, with increasing cooperation from the United Nations, moved ahead with establishment of a provisional government that would assume sovereignty over Iraq. The effort occurred amidst increasing violence that included attacks not simply on allied troops but also Iraqis connected in any way with the new government. Most of the insurgents appeared to be Saddam loyalists; some were indigenous Muslim sectarians; a fair number likely were foreign fighters. It was not clear whether a liberal democratic nation could be created out of such chaos, but certain that the United States could not impose one if Iraqis did not want it.

The 2004 presidential election

By mid-2004, with the United States facing a violent insurgency in Iraq and considerable foreign opposition to the war there, the country appeared as sharply divided as it had been four years earlier. To challenge President Bush, the Democrats nominated Senator John F. Kerry of Massachusetts. Kerry's record as a decorated Vietnam veteran, his long experience in Washington, his dignified demeanor, and his skills as a speaker all appeared to make him the ideal candidate to unite his party. His initial campaign strategy was to avoid deep Democratic divisions over the war by emphasizing his personal record as a Vietnam combatant who presumably could manage the Iraq conflict better than Bush. The Republicans, however, highlighted his apparently contradictory votes of first authorizing the president to invade Iraq, then voting against an important appropriation for the war. A group of Vietnam veterans, moreover, attacked Kerry's military record and subsequent anti-war activism.

Bush, by contrast, portrayed himself as frank and consistent in speech and deed, a man of action willing to take all necessary steps to protect the country. He stressed his record of tax cuts and education reform and appealed strongly to supporters of traditional values and morality. Public opinion polls suggested that Kerry gained some ground following the first of three debates, but the challenger failed to erode the incumbent's core support. As in 2000, Bush registered strong majorities among Americans who attended religious services at least once a week and increased from 2000 his majority among Christian evangelical voters.

The organizational tempo of the campaign was as frenetic as its rhetorical pace. Both sides excelled at getting out their supporters; the total popular vote was approximately 20 percent higher than it had been in 2000. Bush won by 51 percent to 48 percent, with the remaining 1 percent going to Ralph Nader and a number of other independent candidates. Kerry seems to have been unsuccessful in convincing a majority that he possessed a satisfactory strategy to end the war. The Republicans also scored small, but important gains in Congress.

As George W. Bush began his second term, the United States faced challenges aplenty: the situation in Iraq, stresses within the Atlantic alliance, in part over Iraq, increasing budget deficits, the escalating cost of social entitlements, and a shaky currency. The electorate remained deeply divided. The United States in the past had thrived on such crises. Whether it would in the future remained to be seen.