ca. 1735-1830

"Nancy" Hart was born Anne Morgan. She was a hunter, spy, sharpshooter, and herbalist. She was born around 1735 in either North Carolina or Pennsylvania. Her parents were Major Mark Morgan and Sarah (Hinton) Morgan. She grew up in the colony of North Carolina, in the mountains of the Yadkin River valley. Details of her early life are unclear until she met her husband, Benjamin Hart, in Orange County, North Carolina. They married around 1760 and moved to Edgefield, South Carolina. Benjamin and Mark conducted business together in Orange County. They organized wills and transferred land. Sometime in the 1770s, possibly in 1771, Anne and Benjamin moved to Georgia and settled in Elbert County, in a log cabin on the Broad River near Wahachee (Wahatchee) Creek.

Most people in the colonies chose sides during the American Revolution. Some people, like Nancy, were Patriots that supported the Revolution. They were also known as Continentals, Yankees, Whigs, or Colonials. Others supported the British monarchy and were known as Loyalists. Loyalists were also known as Tories, Royalists, or Kings Men. Nancy was known for being a devoted Patriot, who strongly disliked the British and their cause. She dedicated most of her life to fighting against it.

Nancy also fought British and Loyalist soldiers on her own property in the Georgia backcountry on multiple occasions. Oral and folk history documented that she and her daughter were doing household chores during one such instance. Nancy was making lye soap and the liquid was extremely hot. Her daughter noticed a pair of eyes peeking through the wall of their log cabin. She alerted her mother, and Nancy stopped to throw a ladle of steaming soap mixture right into the eye(s) of the British soldier. She tended the soldier's wounds before surrendering him to the Patriots.

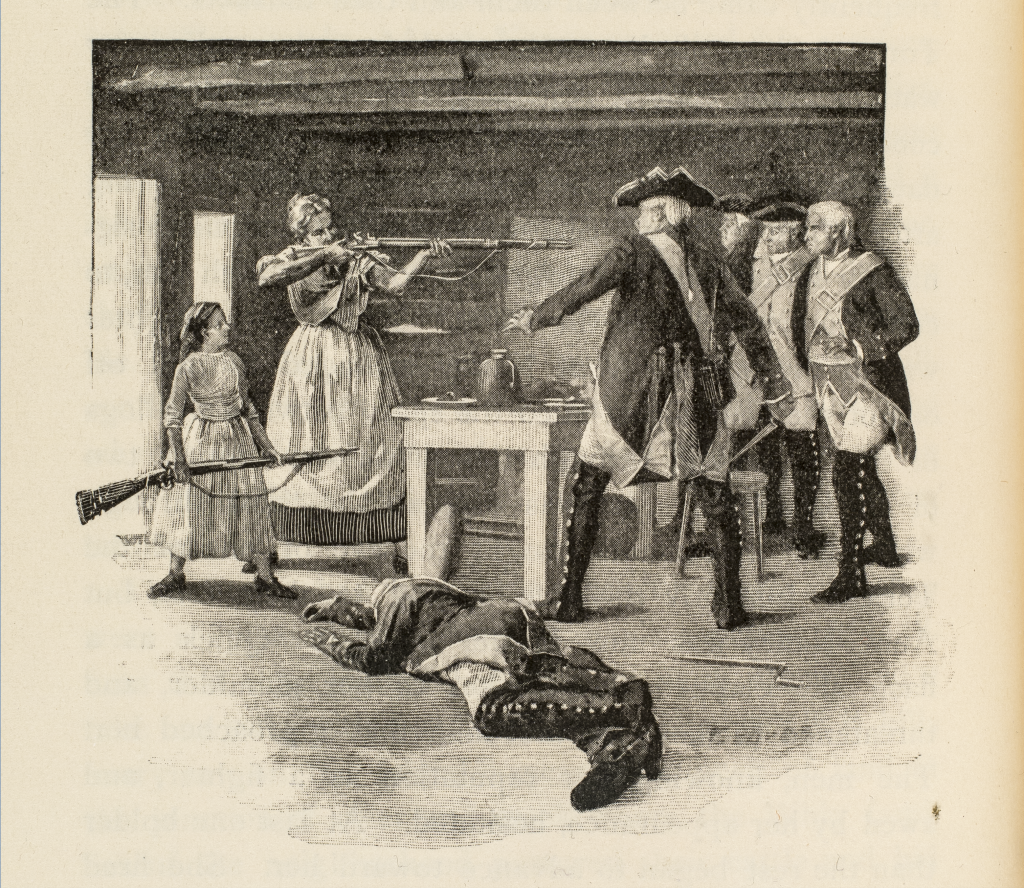

Family, oral, and popular history document another incident that occurred in July 1779. Nancy and her daughter, Sukey, were at the log cabin when six British soldiers came onto the Hart property. The soldiers stated they were looking for a Patriot who escaped them. After much argument over the Patriot soldier, the British soldiers slaughtered one of Hart's turkeys and demanded she make a meal for them with it. During the meal, Hart served the soldiers generous amounts of corn liquor, which intoxicated the soldiers so she could trick them more easily. She then sent Sukey to sound the alarm, calling her husband and sons for help. Nancy snuck their guns outside after the soldiers were drunk. One British soldier noticed what Nancy was doing and alerted the other soldiers. Nancy seized one of their weapons and turned it on the soldiers, warning them to remain still until her family arrived. When a soldier ignored Nancy's warning, she shot and killed him. According to reproduced historical accounts, the remaining soldiers were held captive by Nancy and later hanged by her family.

The popular story of Nancy Hart's heroism against British soldiers was first published about fifty years after the event on October 6, 1825, in the Southern Recorder, the local newspaper of Milledgeville, Georgia. The story was reprinted in the Savannah Republican (GA). The United States government never gave an award or honor to Nancy for her family's battle with the British soldiers. Exact details of the battle are unknown for this reason and due to late newspaper publication. Some researchers also believe the story to be mythology due to these factors.

Nancy became a devoted Christian when her town built a Methodist church. According to the writings of George Rockingham Gilmer, Hart's Methodism was adopted around the time she was living in Edgefield . Gilmer was a former governor of Georgia who claimed to have known Hart personally before she died. According to Gilmer, Hart "heard how the wicked might work out their salvation [at the Methodist congregation]; became a shouting Christian, [and] fought the devil as manfully as she fought the Tories…"

Benjamin Hart died January 2, 1802. After his death, a flood destroyed the Hart cabin in Elbert County. Nancy then "sold out her possessions," and moved to Clarks County, Georgia, to live with her second son, John. She moved with John and his family to Henderson, Kentucky, where she later died. Popular history claims she died around 1830 when she was approximately 95 years old. She left no will, so an exact date is unknown. John's will, dated October 16, 1821, did not include her as the recipient of any property, meaning she likely died before he did.

On December 17, 1912, railway workers were grading and preparing the ground for a railroad site less than a mile from Nancy Hart's cabin. They unearthed six skeletons buried neatly in a row. Georgia newspapers, including the Thomson McDuffie Progress (Thomson, G.A.) reported that the skeletons were located in "Heard field, near the mouth of the Wahatchie Creek, some half of a mile from where it empties into Broad river." The skeletons, all determined to be male, were buried in a shallow grave about three feet deep, and provided important clues to identification. First, their teeth were in good condition. Good teeth meant proper care, especially during the Revolution, and proper dental care was hard to find in rural, Revolutionary Georgia. Skeletons with good teeth likely belonged to people who were not native to the area, like British soldiers. The skeletons also had broken necks, possibly the result of being hanged. The number of skeletons, as well as their sex, condition, and locations led many to believe these skeletons belonged to the British soldiers that stories told were detained by Nancy Hart and later killed by her family.

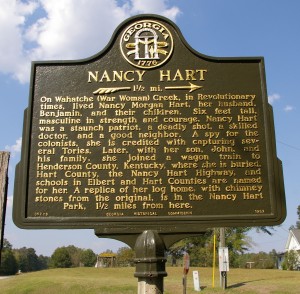

The stories of Nancy Hart's life have inspired many monuments and movements in her honor. On December 7, 1853, the state of Georgia formed a new county from parts of Franklin and Elbert counties, and named it Hart County after Nancy Hart. She is the only woman with a county named after her in Georgia. Near the city of Hartwell, G.A., the U.S. government dedicated a monument to her that says, "To commemorate the heroism of Nancy Hart." During the Civil War, the "Nancy Harts militia" was formed in La Grange, G.A. The all-female unit was composed of wives of Confederate soldiers.

In 1932, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), with the help of the Civilian Conservation Corps, rebuilt Nancy's cabin. The DAR gave the cabin to the state of Georgia, and the area, about 14 acres, was turned into a state park. The cabin is managed by Elbert County today. In addition, many current landmarks in Georgia are also named for Nancy Hart; two such examples are Lake Hartwell and Hartwell Dam.

References:

Crowder, Jack Darrell. Women Patriots in the American Revolution: Stories of Bravery, Daring, and Compassion. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing. 2018.

Coulter, E. Merton. "Nancy Hart, Georgia Heroine of the Revolution: The Story of the Growth of A Tradition." The Georgia Historical Quarterly 39, no. 2 (1955): 118-51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40577562.

"From the Milledgeville Recorder, 17th ult. NANCY HART." The Savannah Republican, October 06, 1825. Accessed June 20, 2023 at https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn87062327/1825-10-06/...

Gilmer, George Rockingham. Sketches of Some of the First Settlers of Upper Georgia, of the Cherokees, and the Author. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1854. Accessed June 20, 2023 at https://archive.org/details/sketchesofsomeof01gilm/mode/2up.

Haun, Weynette Parks. Orange County, North Carolina Court Minutes: 1762-1766. Self-published, 1991.

James, Edward T. Janet Wilson James, Paul S. Boyer, and Radcliffe College. Notable American Women 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge, M.A.: Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press. 1971.

McHenry, Robert. Famous American Women: A Biographical Dictionary from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Dover Publications. 1980.

McIntosh, John H. The Official History of Elbert County, 1790-1935 (Supplement 1935-39 by Stephen Heard Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution, organized 1901, Elberton, Georgia). Edited and published by Stephen Heard Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution. 1940. Accessed June 15, 2023 at https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/245957-the-offic...

"Nancy Hart." The Athenian (Athens, G.A.), Image 4, June 29, 1827. Accessed June 22, 2023 at https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn85027027/1827-06-29/...

"Nancy Hart Cabin." Historic Sites. Elbert County Chamber of Commerce. Accessed June 22, 2023 at https://www.elbertchamber.com/post/historic-sites.

National Society Daughters of the American Revolution of North Carolina, and Ruth Herndon Shields, comp. Abstracts of Wills Recorded in Orange County, North Carolina, 1752-1800 and (202 Marriages Not Shown in the Orange County Marriage Bonds) and Abstracts of Wills Recorded in Orange County, North Carolina, 1800-1850. Genealogical Pub. Co., 1972.

Ouzts, Clay. "Nancy Hart." New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Mar 2, 2020. Accessed June 22, 2023 https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/nancy-h...

"Skeletons of Tories Killed by Nancy Hart Unearthed Tuesday." The McDuffie Progress (Thomson, G.A.), December 27, 1912. Accessed June 20, 2023 at NewspaperArchive.com.

West, Edmund, comp. "Benjamin Hart." The Family Data Collection - Individual Records. Provo, U.T.: Ancestry.com Operations Inc. 2000. Accessed June 20, 2023 on Ancestry.com.

"Will of John Hart." Kentucky, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1774-1989. Kentucky County, District and Probate Courts. October 16, 1802. Lehi, U.T.: Ancestry.com Operations Inc. 2015. Accessed June 20, 2023 at Ancestry.com.