What I want for my daughter, she shall never have: A world without war, a life untouched by the bigotry and hate, a mind free to carry a thought up to the light of pure possibility." -W.D. Ehrhart

I learned from my Daddy that a child should always be willing to listen even if nothing is being said. Silence can be very profound; even silence has its own story to tell. A year of my Daddy's life between 1967 and 1968 was buried in silence until I started digging for that man. Instead of saying anything at all about Vietnam, my Daddy gave me the diary he kept during his tour of duty and all of his photographs from which I learned about Vietnam for myself, through the eyes of a child. With Vietnam, his days as that young man were gone; someone different emerged from those 365 days spent in Vietnam, someone I am still getting to know. I can tell his story because my Daddy has granted me the gift of his voice. He gave me more than just his war story. He gave me permission to speak for him - to remember his memories - to shatter those silences. This has also become my story of Vietnam, and I have been telling it since I was about twelve years old. Like my Daddy's story, it grows, evolves and changes with time. It often takes on a life of its own... living, breathing, moving within spaces, from whispers to deafening cries soberly grieving for the fallen... only to settle back into the story that should always be told, the one that loosens the shackles of silence and spills out into my own voice - the daughter of a Vietnam Veteran - telling my Daddy's story.

September, 23, 1968 would typically read like any other day in my Daddy's diary except that this page was left blank, unlike all the others. There was something that he could not write about... His 365 day tour in Vietnam would end with things left unsaid - unwritten - with this blank page. My father had to imagine that he may not make it back home alive from this war. At age 18, he knew certain things to be a fact: he was poor and black, living and working on a farm in rural Clinton, North Carolina. And, out of all of his brothers, he was the only one drafted to go to Vietnam. With faded photographs and memories scribbled on the back, my Daddy left his home, this small town to serve his country.

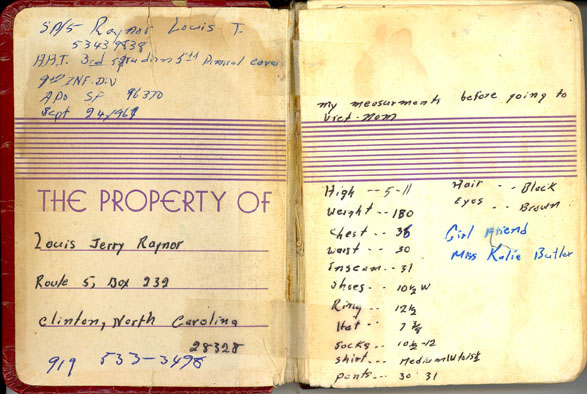

The only thing that mattered to him was that he loved his girlfriend, Miss Katie Mae Butler - of that he was certain. The only other thing left to do before leaving home was to paint a portrait of himself on the front pages of his diary. Just in case this was all that was left, at least someone would know his name, his features, his body measurements, his home, his rank, his squadron, his division - his girlfriend. As a short-timer, infantryman, he knew that he had 365 days to serve before returning home. Though determined, my Daddy was doubtful if he would make it back home alive, and he began his diary, not at the beginning of the book, but on the day that he departed, September 24, 1967.

By his arrival in Vietnam on September 29, 1967, Day 362, he was homesick. The organization of the diary made it very difficult to understand at first. Since the first page of the diary begins with the date January 1, my Daddy chose to record the events of each day on its rightful page until the end of his tour-of-duty when the multiple entries are written on one page. He obviously wanted the diary to represent the chronological order of his tour, but my guess is that he also wanted it to make sense if someone should ever find it and read it and if he was not around to tell the story for himself. There would at least be proof that he was there. He filled the last of his diary pages with the addresses of those he would hope to write and receive letters from while over there, mostly relatives. He saved the memoranda pages at the end of the diary to write about "change of life" events: the birth of his first born daughter on February 25, 1968, Cassandra Lisette, while he was in country and his transition from a civilian to a soldier.

I've always believed that the reason my Dad made it home alive from Vietnam was because of the love of my Mother. As his girlfriend before he was drafted, she would be the one he missed the most because even before his departure and upon his return home, they would marry and start their family together with five children: Cassandra Lisette (1968), Jerry Casino (1970), Tosha Monique (1971), Sharon Denise (1973) and Marquitta Trinease (1983), children who would grow up in the cold silence and haunting shadows of this war, never knowing how it would forever alter our lives. Since I was the baby girl for ten years before my little sister came along and was pretty much ignored by my older brother and sisters, and not to mention, overly curious, I remained fascinated with my Daddy's writings long enough to tell this story.

The first time I saw my Daddy cry was when I was three years old. It was at my Grandfather's funeral, his father. I sat very close to my Dad feeling scared but safe, his arm draped around me like an overcoat. When I saw that tear on my Daddy's cheek, I started to cry. I cried because he cried. I knew that my Granddaddy was with God but all that mattered at that moment was the strength and security I felt in my Daddy's arms. I do not remember feeling that safe ever again.

I always did whatever I could to be in his favor, even if it meant doing something that would get me in trouble. My Mother always kept me involved in different activities when I was growing up because she believed that "idleness is the devil's workshop." And her children were not going to Hell because they had nothing better to do. While in 4-H, I wrote an essay that won first place. The essay was about my hero. I wrote about my Daddy and all the wonderful things he did for our family. I talked about his job as a truck driver, the nights we would sit up late watching the wrestling or old Clint Eastwood movies, and all the loose coins he used to bring home from his trips on the road. He was my hero because I knew then that it took quite a lot to be a daddy to such rowdy children. In the essay, I even mentioned that he was once a soldier, an American hero, or so I thought. I didn't quite understand Vietnam at the time. When Daddy came home from work, I was so excited to show him my essay and the shiny red ribbon attached to it. I knew this would make me his favorite as well as make him forget all the bad things I did to upset Momma while he was away. He was eager to read it but it seemed to make him sad. Instead of giving me a big hug and kiss, he stared blankly out of the window pane in the front door - in silence. I thought for a brief moment that he was crying. But knowing that he would never let me see him cry again, I ran off to play with my brother and sisters. He placed the essay on the table and never said a word about it. I guess I was not his favorite after all. My Momma hung it on the wall.

I never got over my intense fascination with my Dad and what seemed to be his secret life. I guess this stemmed from my mother always saying that I reminded her of my Daddy. For such a petite woman, she possessed a thundering voice, "You are just like your Daddy!" I would often smile at the thought of that, which seemed to have infuriated her even more. I guess that is why she spanked me harder than Daddy would, even if it was for the same offense. Growing up I learned that a diary was someone's secret, a place where they put their private thoughts, where they put all those things that they could not say otherwise. When I found my Daddy's diary, I felt guilty because I had just discovered what I thought was his secret.

I often wondered how I would get to know my father - the man I called my Daddy. I looked at him with great admiration, not because he was my father but because he was a man who carried secrets. Being curious as a child, a person with secrets was always intriguing to me. I wanted to know those secrets because he managed to keep them so silently well all these years. His secrets did not seem to cause any harm to anyone so having a secret could not be such a bad thing. I wanted to possess that power he had to pull this off. I needed to know what it was he kept to himself and how he kept it to himself. Was it painful - could he physically feel the pain, or was it easy to carry?

When I was five years old, my secrets were few: wanting to eat nothing but ravioli, to wear my oldest sister's clothes, and to fight my cousins. By the age of ten, my secrets were no more profound, they just belonged to me: fighting at school, on the school bus, stealing coins from my parents' bureau, and giving my lunch away at school. I was used to whatever punishment came with my offenses. I had become hardened with time like my Daddy. Eager to find loose coins so I could run off to school to buy stickers, gum, or pencils, I accidentally discovered what was lost - or at least - forgotten about for a long time. One day during my scavenger hunt, my hand ran across a piece of cold steel. I pulled from the drawer of my parents' bureau a small gun - a revolver with a few missing pieces. Scattered near it were a few bullets and perhaps the other parts needed to make the gun work. Since there were other guns about the house, like the rifle propped against the wall beside my parents' bed and the one he kept outside for unsuspecting prowlers, this did not fascinate me and so I put it back. Wondering where my Daddy had put the tobacco tin with the loose coins, I slipped my hand back into the drawer. Way in the back, I touched what felt like a book. I pulled it out. I was holding what taught me about Vietnam - my Daddy's diary - old, smelly and falling apart. I quickly lost interest in the loose coins because I had just found a piece of my Dad - tucked safely away near his broken gun, hidden by clothes that belong only in the top drawer of a bureau, out of sight and definitely out of reach - never to be found. Since it was hidden, it obviously piqued my curiosity. I was so fascinated with the diary that I took that instead of the money. The next week at school, I went without the pencils or stickers because I had something no one else did. I never did find out where Daddy moved the tobacco tin. I think he knew about the money and decided to remove the temptation.

Forgetting that I had done something wrong by snooping in my parents' room and the bigger offense, attempting to steal money, I ran to tell Daddy what I had found. He was none too pleased, to say the least. He didn't have much to say. As a matter of fact, he didn't say anything at all. I thought this would make him want to talk to me about when he was a soldier but it didn't. Finding the diary just confirmed that my Daddy had secrets. Now, I knew, much deeper and darker than I had ever imagined. I had to teach myself about Vietnam because my Daddy was still not talking about it. He did, however, give me a photo album filled with old pictures of when he was in Vietnam. Without having to say a word, my Daddy placed enough trust in me to discover Vietnam for myself - to uncover those secrets that he had kept buried for all these years and to see him as that young soldier who almost sacrificed it all.

I almost didn't recognize my Daddy as a young man. He and all the others looked like little boys, unsuspecting and innocent. What could they possibly know about war? They wear the faces of the young, perhaps those who may never grow old because of the inevitability of battle.

For me, the diary was such a treasure to find, and looking at the photographs was like watching time in reverse. But since Daddy was not very interested in talking to me at all about being in the war, I had to read. Page-by-page, I found my Daddy. I learned about his daily routine; I learned about him being in Vietnam. I learned that Advanced Infantry Training (A.I.T.) also meant becoming acquainted with some new friends, the kind that would protect him without question: the M16, M60, rifles and machine guns while carrying their companions, 7 clips, 18 rounds, and clay mortar mines.

The kind of weapons that my family would soon come to know...

The diary began to help me understand why my Daddy was that way... the way the war made him. When we were growing up, Momma taught us certain rules that made little sense at the time: "Never wake your Dad when he is sleeping, even if he is shaking and sweating. Just let him sleep; the nightmare will end." The guns were a constant reminder of the war. The night terrors were horrendous and incomprehensible to small children, and the terror in his eyes when he awoke trembling in a cold sweat was frightening. After years of sleeping in the company of his best friends, my mother asked him to remove the guns from the house. I vaguely remember the incident in which he awoke startled from his sleep and grabbed the nearest rifle to protect himself and his terrain, shivering from a nightmare unknown or an enemy unseen. The only ones in the house were his own family. This was one of the earliest signs that we were living with the war.

I learned that other than my Daddy serving in the 9th Infantry, 3rd Squad/5th Cav Division, he worked mostly with maintenance, Track and Wheel Recovery. He worked to repair heavy machinery and tanks when they were hit or destroyed during battle. I soon learned that going on recovery missions meant much more than bringing exploded tanks back to base camp. It also meant recovering any men lost during battle. The images of the dead bodies at their feet were laid out with the rest of the photos like the days of war.

I began to understand that the soldiers did not fight everyday as it was portrayed on television. The diary reveals very little about the battles but I knew that there were those things that he simply could not or would not say. When he did write about it, he did not say much. He may only mention the trouble but never goes into major detail. His first Christmas while in Vietnam was spent unloading sandbags, enjoying the Bob Hope USO Show and writing home. His New Year's Day was not much better. He did add a note for the reader to find the start of the diary on September 24, 1967.

There was a noticeable change in his diary entries with the start of the new year. He began to write a bit more each day - as if anticipating something. How soon would he learn that 1968 would be considered the bloodiest year of the war? This time during the war would later get named the Tet Offensive, but for my Daddy, he was still adjusting to his constant movement, being attached to A-Troop and B-Troop. He had also been suffering from unusual headaches and desperately wanting sleep. He was also being left behind and constantly waiting for another unit to pick him up.

At this point, he had not mentioned the names of any of the men he was serving with. His photos seem to suggest a brotherhood. And that's exactly what my father and his comrades were doing: working at war, or at least, at what war presented - exploded tanks, destroyed APC's and broken-down V.T.R. M88's.

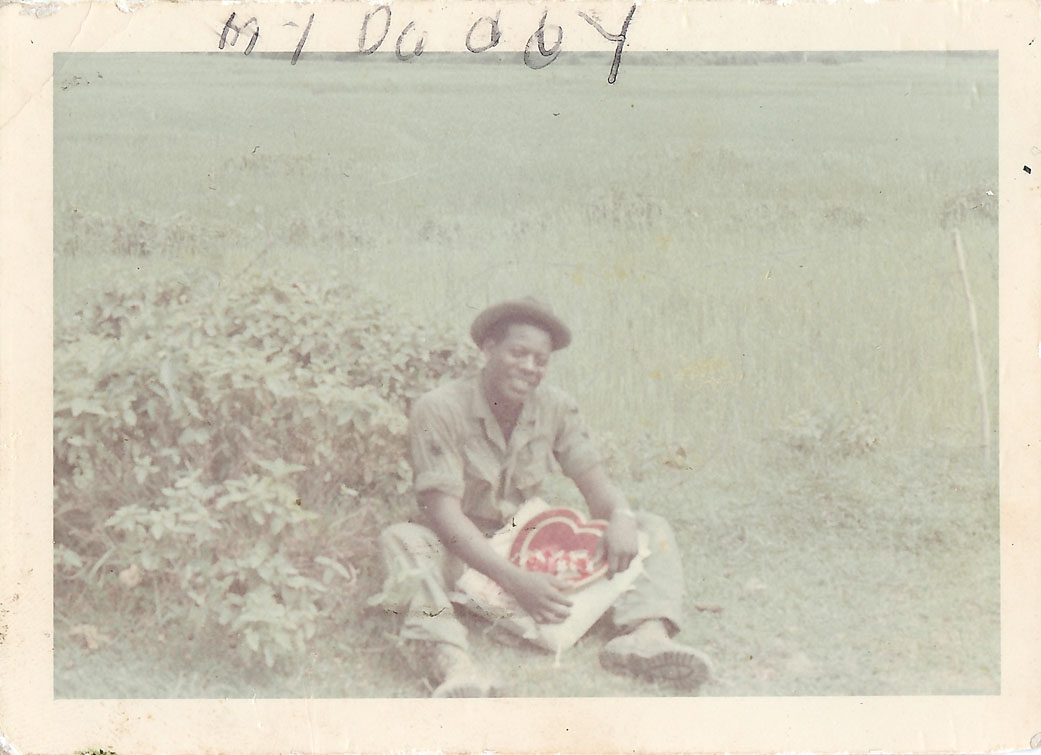

There was always one photograph of my Daddy that I simply loved to look at, even until this day.

It intrigued me because my Daddy seemed so happy.

Even though he didn't talk much about his time in Vietnam, he did remember the many letters, music albums and packages that he received from his girlfriend.

This photo was of a private moment or a brief moment of serenity. How ironic during war time.

It was captured as he thought of my mother.

The box of Valentine's Day candy overshadowed the fact that he was only a few feet away from graves.

The candy seemed to represent his love for her - the reason he would return home.

When telling the story, he would often laugh about how he had a hard time keeping his comrades from eating all of his candy.

I am glad he brought this picture home to us.

As a child, reading the diary confused me a bit because I wanted to believe that my Dad didn't have to fight or kill people. He just needed to fix what was broken. The pictures made me believe that Vietnam was not all bad - there were some laughs. But as I continued to read my Daddy's words, I knew that Vietnam was not all bad - just mostly bad- and the men busied themselves as much as they could simply to stay alert, to be ready. By this time, the war had intensified, and the "dragon wagon," "The Hairy Thing 1" and "The Hairy Thing 2" had become leading characters in my Dad's story. The attacks followed by recovery were pretty consistent now, and my father managed to write about it without emotion - completely detached from the inevitable suffering and death of war.

I was amazed at the constant movement and change of locations my Daddy mentions throughout his writings. Being on the ship as they are headed to Saigon perhaps gave him more time to write, so the entries continued to be a bit longer. By the time he re-attached to B-Troop, the intense fighting seemed to have decreased a bit. But this was indeed war, and there is no mistaking what inevitably may happen next. His entries would soon return to his daily maintenance on the damaged tanks. He went from maintenance to police calls and three formations a day under a new sergeant.

By March 29, Day 186, he was about to move out with C-Troop as they prepared to change locations. His new location would prove to be more dangerous for the troops because they were instructed to wear their flop vests and steel pot helmet liners and to carry their weapons at all times. The loss of eight men with two critically wounded and twenty injured was how the day of filling sandbags ended. By Day 182, he started recording the number of fatalities and wounded from his own troop as well as those of the VC. He seems to almost equate the intensity, the severity and the death toll of the war with the number of vehicles that were either destroyed or damaged. His days were not immune to sniper fire from RPG's or exploding mines.

On Day 173, my Daddy polished his boots for the first time since being in Vietnam. Easter, April 14, 1968 was not a good day for him. My Daddy seems to desperately want to go home now because of some bad news he received, even though he never writes about what happened. No one knew not to send bad news from home to a soldier serving in a war zone. After days of continuous work, eating C-rations, and changing locations, he still anxiously awaits mail from home because he had not received any letters in about nine days. In the meantime, B-Troop continued to lose men. His work seemed to happen simultaneously with the "mess of the war." On Day 146, my Daddy writes about the tank explosion that caused him some minor injuries and burns his face. Because he was not severely wounded enough to be pulled from duty, he returned to work in pain and with some vision problems.

The fighting continued and he spent, Mother's Day, May 12, 1968, Day 137, repairing the engine on the Hairy Thing 1 (M88). The heavy rain started again on May 25, 1968, and it was relentless. The longer he stayed in country, the less he talked about home or even wanting to go home. He did, instead, begin to talk about his comrades and he typically would refer to them simply as his friend. There was a noticeable closeness between the men, despite the fact that serving in this war was probably the first time that most of them had lived and worked amongst each other. Transitioning from attending segregated schools to serving in integrated battalions forced my Daddy into quite a new and unfamiliar environment.

By Day 96, his own troops were experiencing problems amongst themselves while still being in constant contact with the enemy, without much ammunition. By this time, Martin Luther King, Jr. had been assassinated and the troops had been receiving this news while in the midst of war. He also started to talk more about drinking and getting wasted as much as possible. He was even receiving liquor from home. He was spending a lot of time at the beer tent for several days in a row. Once they stopped receiving free beer, they resorted to drinking warm water. I remember that my Daddy's drinking followed him home. The drinking not just suppressed his nightmares and the memories of Vietnam but it also caused major problems for our family. My Mother eventually gave him a choice, and he chose his family over the drinking that helped him forget Vietnam.

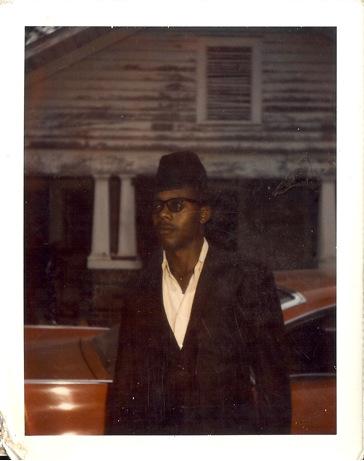

By July 29, 1968 his friend, Chadman, had to return home on an emergency leave. Chadman is the only person that he mentions more than once in the latter entries in the diary. I always assumed that they were truly friends. For my Dad, many names and faces have faded but that is the one that he wrote down. By Day 53, my Daddy was still receiving liquor from home and still drinking constantly. He prepares for R&R about a month before his 365 day tour was to end. He writes about the many luxuries that were just a phone call away. He seems to be extremely tired, but I can only imagine what he must have been thinking about the moment he stepped outside that war zone and looked at the world again. And then to have to return back there in a few short days. Even when he writes about hiring a "waitress" for the night because it "sounded nice," his tone was very somber, a bit restless and uncertain. Even though he looked suave and debonair in his photos, a man in deep thought, for my Dad, R & R seemed far from rest and relaxation.

As the rain continues to take on a life of its own, he returned from R&R and worked constantly. He started preparing for his departure home, and he frantically writes short entries as he nears that last day in Vietnam. Once he returned to the Old Reliable Academy, he was at a complete loss of both time and words...

Preparing to return home, he still writes. Yet, the completion of his journey would end with this blank page. There are no words left to say when a soldier returns home; there are no parades, no marching bands, no family with happy tears screaming his name because they missed him. There is no homecoming, no debriefing, no handshakes or pats on the back for a job well done. Just a generic letter all military personnel received from the government that says "Thank You".

Just his brother waiting to drive him home - to my mother who waited for him, with their new baby girl.

There was nothing left to write about, so his tour ends with this blank page.

I have spent so much time with my Daddy's diary and photographs that they have become a part of me. The photographs are etched in my memories, as are the diary entries. I can remember the dates and places of his tour as well as he can. The still movement of men in the photos captivated me many years ago. I always believed that these nameless soldiers somehow protected my Dad - and he did the same for them. Even now when I want to talk to him about that time, I am careful and cautious to only ask one question at a time about some minute detail that he wrote about all those years ago. He reluctantly responds, at first, but then he talks more openly and freely long after I thought the conversation was over. He always sounds curious as to why I am still interested in this time of his life. He provides the details as I ask them, not much more. Even after reading my Daddy's dairy and then reading it again and again, I still have so many questions- not so many questions about the war itself, but mostly about my Dad. He has always been so proud to have answered that call to serve - to finally get the chance to get away from that farm - to prove his manhood - to demonstrate his American-ness. As his child, it is difficult sometimes to understand this because he didn't return home the same; he was forever changed. His mother saw it in him first - their relationship changed, and his brother, PeeWee, noticed as well. But then there was my mother, who loved him in spite of the war; she loved him through the war, and their thirty-nine year marriage is a testimony to that battle. Sometimes I think about that young man who left home for war in 1967 whom I will never meet. I only really know the man who had been changed by the war, whose eyes hide the unspeakable but whose mind closes around it like a tighten fist - the man who could drive any large vehicle and who could repair almost anything with an engine, who had an uncontrollable desire to be outside (most of the time) in his own terrain, isolated from the world and the sounds of his family - the man who rarely attended any of our school events or ballgames because driving trucks long distance is when he felt most at peace. I have only known the man who could never quite tell us why he was always sick or feeling bad or in the hospital or out of work. And still, he never blamed the war.

Since he had returned home all those years ago, Vietnam was rarely mentioned unless we were at the VA Hospital. We have been to them all... in North Carolina, anyway. The care is all the same - minimum at best. As a child, I didn't know just how sick he was, but I have since watched this warrior of a man slowly deteriorate physically. But, emotionally and spiritually, he has never been stronger - the aftermath of war, I guess. My Daddy's diary is a hard story for a child to read, even harder for a child to understand. As for me, wanting so desperately to understand my Daddy's past kept me turning those pages seeking more. I wanted those pages to turn him into a warrior, a hero, or perhaps even a killing machine. At times, I was not certain exactly what I desired, but often times I craved more. I guess I needed for the diary to tell me just how different my Daddy would become during the war, how different he is when he returned home - that the war would change him, unrecognizable to even his own mother and father. I needed to know what Agent Orange would do to him - to us. The diary needed to tell me that all his ways - his conditions - would be "service-connected." The photographs of recovery, exploded tanks, men in army greens, sandbags, men holding guns was just a façade of the war within the war. My Dad and all the rest of the men were fighting to return home, and he did, changed with new memories, with the traumas and tragedies of the war burned into the sketches of his life. But, the war does not teach a young soldier how to return home, how to "readjust" and enjoy those freedoms they fought for. So home becomes intertwined with his memories of war. And those entanglements have now become our memories - my memories of my Daddy.

My biggest fear is that my Daddy will fade away in the night - walk silently away from all of the chaos - heaped upon his life by the war - lay it all down, so to speak. I know that he would be perfectly fine with leaving this world behind - that, too, lies right there behind his eyes. My mother's love keeps him safe and knowing that those memories are her memories as well. Throughout his diary, he never says that he loves her, but he does say that he misses home perhaps missing her. And, he returned to us... to start his life again the only way that he knew how.