The first group of Montagnard refugees were mostly men who had fought with the Americans in Vietnam, but there were a few women and children in the group as well. The refugees were resettled in Raleigh, Greensboro, and Charlotte, North Carolina, because of the number of Special Forces veterans living in the area, the supportive business climate with numerous entry-level job opportunities, and a terrain and climate similar to what the refugees had known in their home environment. To ease the impact of resettlement, the refugees were divided into three groups, roughly by tribe, with each group resettled in one city.

Beginning in 1987, the population began to grow slowly as additional Montagnards were resettled in the state. Most arrived through family reunification and the Orderly Departure Program. Some were resettled through special initiatives, such as the program for reeducation camp detainees, developed through negotiations between the U.S. and Vietnamese governments. A few others came through a special Amerasian project that included Montagnard youth whose mothers were Montagnard and whose fathers were American.

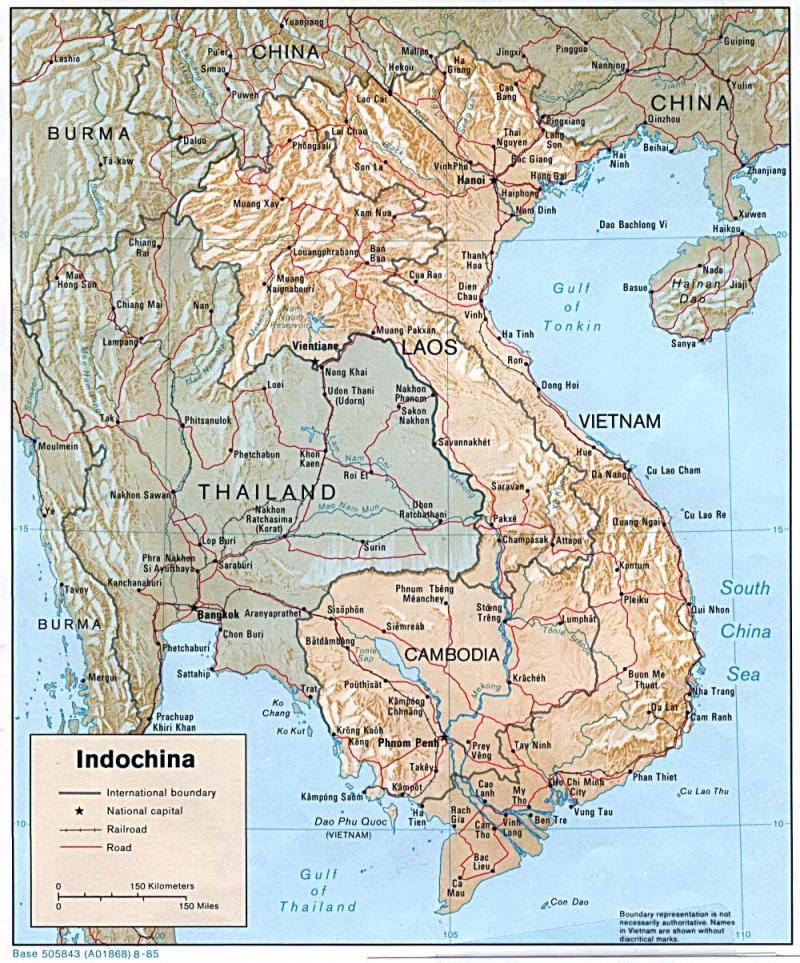

In December 1992, a group of 402 Montagnards were found by a UN force responsible for the Cambodian border provinces of Mondolkiri and Ratanakiri. Given the choice to return to Vietnam or be interviewed for resettlement in the United States, the group chose resettlement. They were processed and resettled with very little advance notice in the three North Carolina cities. The group included 269 males, 24 females, and 80 children.

Through the 1990s, the Montagnard population in the United States continued to grow as new family members arrived and more reeducation camp detainees were released by the Vietnamese government. A few families settled in other states, notably California, Florida, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Washington, but by far North Carolina was the preferred choice for the Montagnards. By 2000, the Montagnard population in North Carolina had grown to around 3,000, with almost 2,000 in the Greensboro area, 700 in the Charlotte area, and 400 in the Raleigh area. North Carolina had become host to the largest Montagnard community outside of Vietnam.

In February 2001, Montagnards in Vientam's Central Highlands staged demonstrations relating to their freedom to worship at local Montagnard churches. The government's harsh response caused nearly 1,000 villagers to flee into Cambodia, where they sought sanctuary in the jungle highlands. The Vietnamese pursued the villagers into Cambodia, attacking them and forcing some to return to Vietnam. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees granted refugee status to the remaining villagers, most of whom did not want to be repatriated.

In the summer of 2002, close to 900 Montagnard villagers were resettled as refugees in the three North Carolina resettlement sites of Raleigh, Greensboro, and Charlotte, as well as in a new resettlement site, New Bern. The new population of Montagnards, like previous groups, is predominantly male, many of them having left wives and children behind in their haste to escape and with the expectation that they could return to their villages. A few intact families are being resettled.

How have the Montagnard newcomers fared? For the most part, those who came before 1986 adjusted quite well given their backgrounds -- war injuries, a decade without health care, and little or no formal education -- and given the absence of an established Montagnard community in the United States into which they could integrate. Their traditional friendliness, openness, strong work ethic, humility, and religious beliefs have served them well in their adjustment to the United States. The Montagnards rarely complain about their conditions or problems, and their humility and stoicism have impressed many Americans.

Among those who came between 1986 and 2000, able-bodied adults found jobs within a few months and families moved toward a low-income level of self sufficiency. Montagnard language churches were formed and some people joined mainstream churches. A group of recognized Montagnard leaders, representing the three cities and various tribal groups organized a mutual assistance association, the Montagnard Dega Association to help with resettlement, maintain cultural traditions, and assist with communication.

The adjustment process has been more difficult for the 2002 arrivals. This group had relatively little overseas cultural orientation to prepare them for life in the United States, and they bring with them a great deal of confusion and fear of persecution. Many did not plan to come as refugees; some had been misled into believing that they were coming to the United States to be part of a resistance movement. Moreover, the 2002 arrivals do not have political or family ties with the existing Montagnard communities in the United States since they come from villages and tribes that were not part of the earlier resistance movement.