Several sources of conflict arose between the British colonists and the Tuscarora. While it would seem that land was plentiful, the Native Americans built their villages on riverbank locations sought by colonists who looked for fertile soil and access to water transportation. The European settlers often cheated the Native Americans in trade and sometimes stole from them or killed them to obtain goods; the increasingly brisk enslavement and trade in enslaved people further depleted the populations of American Indian tribes and their people. Other problems arose from the intrusion of a culture that clearly defined land ownership upon another whose notions of ownership were much more subjective. To the Tuscarora, land and the animals that roamed it were not personal property, but natural resources available to anyone in need. Yet, what they personally grew belonged to the grower, and they respected that ownership. But the colonists rarely understood when a Tuscarora raiding party took their livestock, or when they set fire to the land before their annual hunts in a ceremony that often destroyed timber and farmland claimed by settlers.

At first, both sides tried to avoid armed conflict. The colonial government signed treaties with the Tuscarora designed to protect their land and to ease trade relations, but the settlers often ignored or blatantly dishonored these agreements. In 1710, the Tuscarora attempted to emigrate to Pennsylvania but were denied permission by the Pennsylvania government because the colony's law forbidding the importation of enslaved American Indian people was written in such broad terms that it forbade immigration of American Indian people as well. The Tuscarora sought but never received from North Carolina's colonial Government a guarantee of their good behavior, a document that may have allowed them entrance into Pennsylvania. In the end, the Tuscarora were forced to remain on the frontiers of encroaching European settlement and to accept into their midst an increasing number of Native American refugees forced from their land. Warfare became inevitable.

Shortly after the death of John Lawson in 1711, the Tuscarora chief Hancock organized a force of 500 warriors to drive out the colonists. On the morning of 23 September 1711, small raiding parties began assaulting plantations near Bath. The colonists, who had not anticipated bloodshed, were low on supplies and ammunition. Moreover, they were left with no time to retaliate: a small band of Tuscarora would approach each isolated plantation in their everyday manner, then attack without warning. They slew both men and women, children and adults, and often mutilated the bodies of their victims. Three days of carnage claimed the lives of 130 settlers and reduced the countryside to ashes and ruins.

In response to the attacks, Governor Edward Hyde convinced the State Assembly to pass a bill to draft all men between the ages of 16 and 60, but even this measure proved insufficient because food and weapons were scarce and because the Quaker settlers refused to bear arms. Hyde sent to Virginia for assistance, but the Virginians would not advance their troops beyond the state line unless North Carolina would promise to surrender tracts of land along the border. Refusing to accept such political blackmail, Hyde solicited aid from South Carolina.

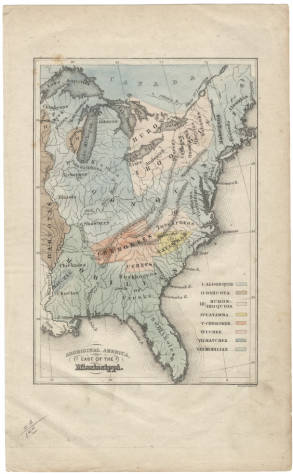

Without asking for concessions, the South Carolina government sent Col. John Barnwell, a veteran fighter against American Indian tribes and their people, with a force of 30 white officers and 500 Native American soldiers from an array of South Carolina tribes, including the Wateree, Congaree, Waxhaw, Pee Dee, Appalachee, and Yamasee. Having to travel over 300 miles through the wilderness, Barnwell didn't arrive until January 1712. Reinforced by 50 North Carolina militiamen, Barnwell forced the Tuscarora to retreat to a fort in Greene County, where they eventually surrendered and released their prisoners.

This victory, however, did not end the Tuscarora War. Moreover, all involved found themselves dissatisfied. North Carolina expected Barnwell to defeat the Tuscarora completely, while South Carolina expected some sort of repayment. And some South Carolina officers retained Tuscarora prisoners to sell as slaves, a breach of treaty that led to renewed discontent and precipitated a second wave of Tuscarora attacks the following summer.

When these renewed attacks came, the settlers were already weakened by a yellow fever epidemic that had claimed many lives, including that of Governor Hyde. Still struggling to rebuild their plantations, many abandoned the colony. Some fled to Virginia; others huddled in garrisons to avoid Tuscarora raiding parties. The new governor, Thomas Pollock, turned to South Carolina again. In December 1712, Col. James Moore arrived with 33 whites and nearly 1,000 Native Americans and won a sound victory, killing over 900 warriors and effectively breaking the power of the Tuscarora.

In the wake of the war, the Tuscarora emigrated on their own, joining the Iroquois of the Long House in New York. Entire villages left at first, and those that remained trickled northward in small bands, the last leaving North Carolina in 1802. The surviving colonists, meanwhile, emerged from the garrisons to rebuild in the ruins.