In the 1950s, Hugh Morton trained his camera on Cherokee, North Carolina, documenting the substantial tourism boom that had developed on the Eastern Band of Cherokees' Qualla Boundary reservation. He photographed Cherokee potters and basket-makers, along with the Cherokee "chiefs" who posed for tourist snapshots wearing Hollywood Indian garb. He created a particularly striking set of images capturing scenes from Unto These Hills, the outdoor historical drama that debuted in 1950 and quickly became one of North Carolina's most popular tourist attractions. These photos provide a vivid record of an important moment in the history of both the Eastern Band and the mountain region as a whole.

Significant Cherokee tourism development had begun in the 1930s, driven by the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park on land adjacent to the reservation. Visitors to the Smokies often paused at the Qualla Boundary, looking for Indian sights and souvenirs, and tourism promoters quickly came to view the Cherokee presence as a major asset. The Bureau of Indian Affairs and some tribal leaders joined in tourism planning during this time, hoping the industry might provide economic opportunities for the reservation community. They worked to beautify the approach to the park, for instance, and encouraged Cherokee schools to improve instruction in crafts like basketry. They also drafted plans for tribally run tourist accommodations.

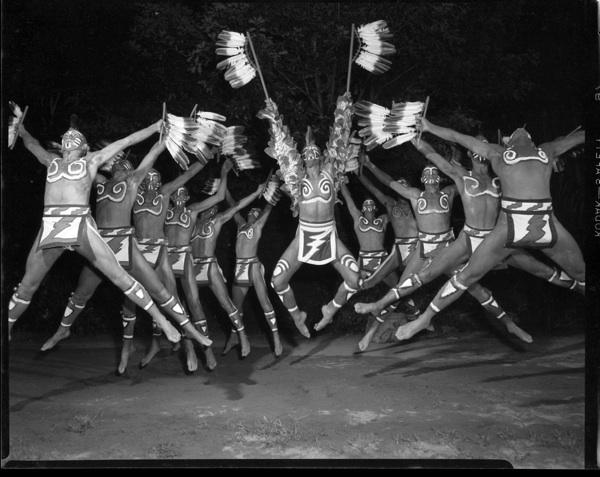

Tourism slowed during World War Two, but when peace returned, accompanied by economic prosperity, the industry revived, growing stronger than ever. In the late 1940s, the Eastern Band completed the Boundary Tree project, a tribally owned motel and service station located near the park entrance. Around the same time, a group of regional business leaders formed the Cherokee Historical Association (CHA), with the goal of creating tourist attractions rooted in Cherokee culture and history. Their first project was the drama "Unto These Hills," an immediate success that drew more than 100,000 viewers in its first season alone. The CHA later developed the Museum of the Cherokee Indian and built the Oconaluftee Indian Village, a re-creation of an eighteenth-century Cherokee town. Attractions like these did not always present the Cherokee past accurately, but they certainly proved effective, bringing thousands of vacationers (and their money) to Cherokee each summer.

Yet tourism was not only Cherokee story in these years. The post-war era also witnessed a growing political assertiveness on the part of Cherokees, a trend that foreshadowed the Eastern Band's emergence, later in the century, as an influential political player in the region. In the late 1940s, for instance, Cherokee war veterans organized to win the right to vote. For decades, local election officials had routinely refused to register tribal citizens, applying to Cherokees some of the same tactics used to disfranchise African Americans. Having fought totalitarianism overseas, Cherokee veterans found this denial of their civil rights at home intolerable. In 1946 members of the American Legion post at Cherokee began to press officials in Swain and Jackson Counties to permit Indians to register. Ignored, they mounted a public relations campaign to broadcast their grievances and appealed to the federal Justice Department, which sent FBI agents to investigate. They also enlisted the help of other American Legion posts, inviting non-Indian veterans to lend their support to the Cherokee cause. By the end of the year, county officials relented and began to register Cherokees. That effort, it is worth noting, was one of several cases nationwide in which Native American war veterans successfully challenged state and local barriers to Indian voting.

A few years later, Cherokees faced a greater political challenge when the Eastern Band became a target of the federal government's termination campaign. Termination was the policy of ending the protective trust status of reservation land and withdrawing federal services like health care and education. The policy aimed to dismantle the special relationship between the federal government and Indian tribes and, as quickly as possible, place tribal members in a status identical to that of other American citizens. While Indian people certainly chafed under the restrictions imposed by the federal relationship, many worried that termination would result in the loss of reservation lands and the disintegration of tribal communities. They viewed the policy as a new path to the old American goal of Indian assimilation.

In the early 1950s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs began work to bring the termination policy to the Eastern Band, negotiating with state and local officials to take over services to Cherokee communities as the federal government withdrew. The Bureau quickly discovered, however, that many Cherokees distrusted the new initiative. Although some supported termination in the hope of freeing themselves of the Bureau, many more feared the policy. When a House of Representatives subcommittee held hearings on termination on the Qualla Boundary in 1955, a long line of tribal citizens, led by Principal Chief Osley Saunooke, expressed their doubt and opposition, one witness likening the policy to the nineteenth-century gold rush that had helped to precipitate the Trail of Tears. Rather than termination, they favored policies that would promote economic development and improved social services within the federal relationship. This Cherokee resistance belonged to a broader trend that saw Indian communities across the country organizing to oppose termination, a movement that some historians identify as the start of a major Native American political revival in the second half of the twentieth century.

Hugh Morton's tourism photography did not depict these political events; however, the history of tourism in western North Carolina intersects with modern Cherokee politics in some interesting and important ways. As the historian John R. Finger notes, the success of projects like Unto These Hills convinced some non-Indian residents that having a Native American community in the region was good for business. As a consequence, policies that threatened the Eastern Band promised also to undermine the regional economy. Acting on such reasoning, some tourism promoters in the 1950s joined Cherokee leaders like Osley Saunooke in fighting termination. So perhaps Morton's well-crafted photos are more than reminders of familiar attractions. Placed in their proper context, they allude to mid-century economic and political transformations that today still shape the lives of mountain residents, Cherokee and non-Indian alike.