The rise of African American popular music in Winston-Salem, 1920-1960.

At the beginning of the 20th century, an African American gospel tradition emerged which incorporated blues sounds. Later in the century, gospel gave birth to rhythm and blues, in which gospel music sounds were stripped of sacred lyrics and replaced with secular ones. This evolution from gospel to rhythm and blues occurred all over the South, and certainly in cities like Winston-Salem with its large and vibrant African American community.

African American gospel is often viewed as a hybrid music form. Thomas Dorsey, commonly cited as the father of gospel music, actually began his musical career recording jazz and blues compositions. He later integrated these musical ideas into older spiritual traditions and helped create African American gospel music. Winston-Salem gospel radio announcer Tim Jackson, Jr. concurs with this view: "I think of gospel in terms of a blend of sacred, spiritual, and hymns with a jazz and blues style. I'm looking at the history of our music, and this is how Thomas Dorsey put it together."1

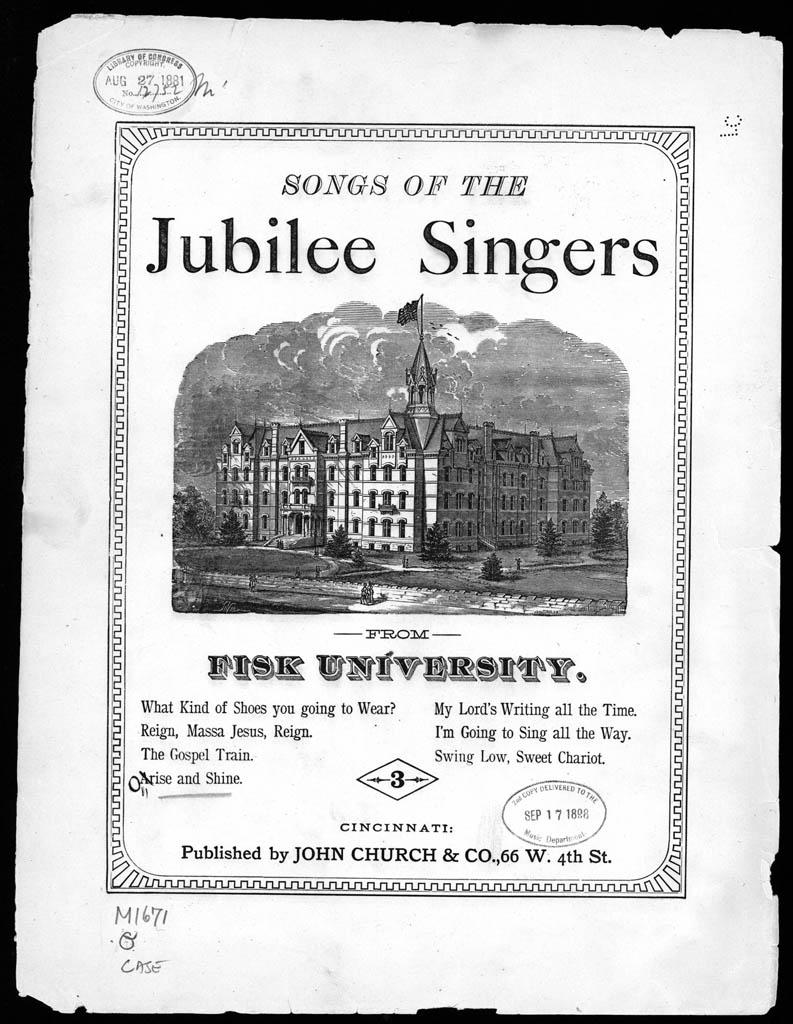

In the early 20th century, many African American families in the Northwest Piedmont were rooted in the community quartet tradition that would act as a predecessor to early gospel traditions. This a cappella quartet tradition was based on the singing of the Fisk Jubilee singers, and the gospel quartet groups were originally labeled "jubilee quartets." Recording artist Bernice Johnson Reagon describes their jubilee aesthetic as "characterized by a smooth, restrained... style of choral singing."2

Over time, the sound of these quartets was experiencing considerable change. As Reagon explains, "In the 1930s, solo leads evolved that mirrored the preaching tradition, and the jubilee quartet became the gospel quartet. This change saw the prolific creation of new songs and arrangement techniques."3

John Tanner, Sr. and the Tanner Family

During this period, the Tanner brothers of Winston-Salem -- John, David, Purnell, Eugene Jr., and Fred -- were among the many young men soaking up the new sounds of gospel quartets and quintets. Sons of E. E. Tanner and his wife Marie, natives of South Carolina who moved to Winston in the '20s to work at R.J. Reynolds, the Tanner brothers grew up in a very religious and musical family, performing gospel songs with their parents in church and on the road.

Dr. Fred Tanner recalls spending Sunday afternoons after church with his brothers practicing pieces for the inevitable Sunday evening performance. As Dr. Tanner recounts, "We got our repertoire from the recordings of 'The Five Blind Boys,' 'The Soul Stirrers,' 'The Pilgrim Travelers,' all those groups... We'd go get the records and... learned the parts right off the recordings."4

The eldest Tanner son, John, was a member of the Royal Sons, a local quintet consisting of voice and guitar helping to define these new gospel sounds in Winston-Salem. The group sang in local African American churches, as well as at gatherings for white Winston-Salem residents. They also performed on radio stations WSJS and WAIR. A friend suggested they send some of their recordings to New York's Apollo Records. Their test cut, the gospel standard "It's Gonna Rain," gained them an audition and finally a record contract.

When the Royal Sons traveled to New York, they honestly didn't know what kind of group they were about to become. At their first session, the group, including Lowman Pauling, Johnny Holmes, Jimmy Moore, and Otto Jeffries, recorded equal amounts of gospel and R&B material. They had been regularly switching between gospel and the secular music, depending on what their audience dictated. According to John Tanner, "We could (switch) easy... Oh yeah, we was singing in different places, hotels and things, Christmas parties."5

According to Tanner, at the Apollo recording session, "they were testing to see which one went." Two subsequent number-one R&B hits off back-to-back recording sessions, "Baby, Don't Do It" and "Help Me Somebody," answered which one "went." The gospel quintet the Royal Sons would soon become the Five Royales, who would help father the new sounds of rhythm and blues. During their fourteen-year career, the Five Royales, described by Juke Blues magazine as "one of the most important R&B vocal groups from the 1950s," recorded five top-ten rhythm and blues hits.6

- 1. Comments made by Tim Jackson, Jr. on tape recording from gospel specialists meeting for project at Winston-Salem State University, February 18, 2002.

- 2. Reagon, B.J. (Editor) (1992). We'll Understand It Better By and By: Pioneering African American Gospel Composers. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, p.14.

- 3. Reagon, B.J. (Editor) (1992). p. 14.

- 4. From phone interview with Dr. Fred Tanner, 2002.

- 5. Egan, S. (1994) "The Five Royales, Part I," Juke Box Blues. No. 31, p.10.

- 6. Steadman, T. "R&B Kings of a Bygone Era," The Greensboro News & Record, from press files of the North Carolina Arts Council. (Date and page unknown to author.)