As factories grew, employers demanded more and more of their workers. To increase profits, they insisted on longer work days — often twelve hours a day, six days a week. There was little concern for safety; machines were dangerous, and factories often had poor lighting and ventilation. And workers' pay stayed low, because it was easy for factory owners to find more workers.

To bargain more effectively with large employers, workers began forming labor unions. They knew that individually they could not effect change, but that by working together — by going on strike — they could shut down a factory and demand changes in their wages and working conditions.

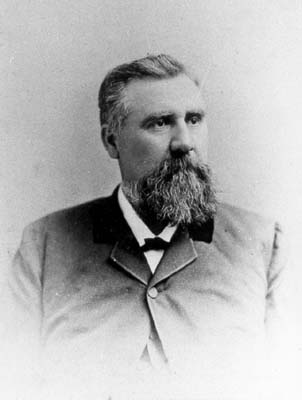

When a factory's workers went on strike, the owner had a few options. He could negotiate and give them what they wanted, but few factory owners wanted to give workers that kind of power. The owners of some factories used police or private detectives to violently break up strikes. As you can read here, W. T. Blackwell & Co. took a simpler option: They fired the strikers and replaced them with new workers (who were called scabs by strikers) — probably new immigrants — from New York.

Although many strikes were ineffective, labor unions would eventually be responsible for many of the working conditions we take for granted today — the eight hour day, weekends, health care, workers' compensation for injuries, safety inspections, a ban on child labor, and the minimum wage.

W. T. BLACKWELL & CO. SETTLE A STRIKE QUICKLY

On Friday morning the cigarette hands in the factory of Blackwell & Co., Durham, N.C., eighty-nine in number, on entering their department very coolly took their seats and turned their backs upon their work. It was soon perceived that a strike was on foot. Mr. W. T. Blackwell was sent for at once. He is not a bit of an orator, but a most effective speaker, going at once to the point. He asked what was wanted. The leader, an Englishman, announced that they wanted the discharge of the inspector of cigarettes, and they wanted more pay. "As for the first," said Mr. B., "I propose to run this establishment. I selected my inspector. The reputation of my factory depends on my judgment. As for more pay, I will not yield to demands made in this way. Now let every one of you go back to his work. I will give you one minute to do that. If not, there is a door big enough for you all to go out fast enough. Take your choice."

All went back to work, and thus ended the strike.

But to guard against a recurrence, Mr. Blackwell dispatched a representative to New York by the evening train to engage a sufficiency of first-class workmen.

Source Citation:

"W. T. Blackwell & Co. Settle a Strike Quickly." U.S. Tobacco Journal, August 6, 1881.