Cold War aims

The Cold War was the most important political and diplomatic issue of the early postwar period. It grew out of longstanding disagreements between the Soviet Union and the United States that developed after the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Soviet Communist Party under V.I. Lenin considered itself the spearhead of an international movement that would replace the existing political orders in the West, and indeed throughout the world. In 1918 American troops participated in the Allied intervention in Russia on behalf of anti-Bolshevik forces. American diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union did not come until 1933. Even then, suspicions persisted. During World War II, however, the two countries found themselves allied and downplayed their differences to counter the Nazi threat.

At the war's end, antagonisms surfaced again. The United States hoped to share with other countries its conception of liberty, equality, and democracy. It sought also to learn from the perceived mistakes of the post-WWI era, when American political disengagement and economic protectionism were thought to have contributed to the rise of dictatorships in Europe and elsewhere. Faced again with a postwar world of civil wars and disintegrating empires, the nation hoped to provide the stability to make peaceful reconstruction possible. Recalling the specter of the Great Depression (1929-1940), America now advocated open trade for two reasons: to create markets for American agricultural and industrial products, and to ensure the ability of Western European nations to export as a means of rebuilding their economies. Reduced trade barriers, American policy makers believed, would promote economic growth at home and abroad, bolstering U.S. friends and allies in the process.

The Soviet Union had its own agenda. The Russian historical tradition of centralized, autocratic government contrasted with the American emphasis on democracy. Marxist-Leninist ideology had been downplayed during the war but still guided Soviet policy. Devastated by the struggle in which 20 million Soviet citizens had died, the Soviet Union was intent on rebuilding and on protecting itself from another such terrible conflict. The Soviets were particularly concerned about another invasion of their territory from the west. Having repelled Hitler's thrust, they were determined to preclude another such attack. They demanded "defensible" borders and "friendly" regimes in Eastern Europe and seemingly equated both with the spread of Communism, regardless of the wishes of native populations. However, the United States had declared that one of its war aims was the restoration of independence and self-government to Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the other countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

Harry Truman's leadership

The nation's new chief executive, Harry S Truman, succeeded Franklin D. Roosevelt as president before the end of the war. An unpretentious man who had previously served as Democratic senator from Missouri, then as vice president, Truman initially felt ill-prepared to govern. Roosevelt had not discussed complex postwar issues with him, and he had little experience in international affairs. "I'm not big enough for this job," he told a former colleague.

Still, Truman responded quickly to new challenges. Sometimes impulsive on small matters, he proved willing to make hard and carefully considered decisions on large ones. A small sign on his White House desk declared, "The Buck Stops Here." His judgments about how to respond to the Soviet Union ultimately determined the shape of the early Cold War.

Origins of the Cold War

The Cold War developed as differences about the shape of the postwar world created suspicion and distrust between the United States and the Soviet Union. The first - and most difficult - test case was Poland, the eastern half of which had been invaded and occupied by the USSR in 1939. Moscow demanded a government subject to Soviet influence; Washington wanted a more independent, representative government following the Western model. The Yalta Conference of February 1945 had produced an agreement on Eastern Europe open to different interpretations. It included a promise of "free and unfettered" elections.

Meeting with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov less than two weeks after becoming president, Truman stood firm on Polish self-determination, lecturing the Soviet diplomat about the need to implement the Yalta accords. When Molotov protested, "I have never been talked to like that in my life," Truman retorted, "Carry out your agreements and you won't get talked to like that." Relations deteriorated from that point onward.

During the closing months of World War II, Soviet military forces occupied all of Central and Eastern Europe. Moscow used its military power to support the efforts of the Communist parties in Eastern Europe and crush the democratic parties. Communists took over one nation after another. The process concluded with a shocking coup d'etat in Czechoslovakia in 1948.

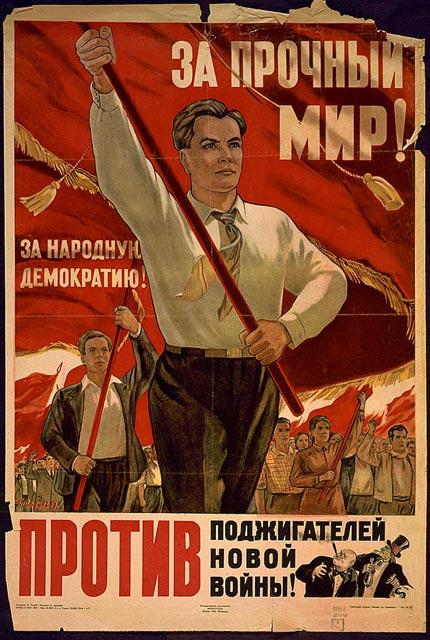

Public statements defined the beginning of the Cold War. In 1946 Stalin declared that international peace was impossible "under the present capitalist development of the world economy." Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered a dramatic speech in Fulton, Missouri, with Truman sitting on the platform. "From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic," Churchill said, "an iron curtain has descended across the Continent." Britain and the United States, he declared, had to work together to counter the Soviet threat.

Containment

Containment of the Soviet Union became American policy in the postwar years. George Kennan, a top official at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, defined the new approach in the Long Telegram he sent to the State Department in 1946. He extended his analysis in an article under the signature "X" in the prestigious journal Foreign Affairs. Pointing to Russia's traditional sense of insecurity, Kennan argued that the Soviet Union would not soften its stance under any circumstances. Moscow, he wrote, was "committed fanatically to the belief that with the United States there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted." Moscow's pressure to expand its power had to be stopped through "firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies. ..."

The first significant application of the containment doctrine came in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. In early 1946, the United States demanded, and obtained, a full Soviet withdrawal from Iran, the northern half of which it had occupied during the war. That summer, the United States pointedly supported Turkey against Soviet demands for control of the Turkish straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. In early 1947, American policy crystallized when Britain told the United States that it could no longer afford to support the government of Greece against a strong Communist insurgency.

In a strongly worded speech to Congress, Truman declared, "I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures." Journalists quickly dubbed this statement the "Truman Doctrine." The president asked Congress to provide $400 million for economic and military aid, mostly to Greece but also to Turkey. After an emotional debate that resembled the one between interventionists and isolationists before World War II, the money was appropriated. Critics from the left later charged that to whip up American support for the policy of containment, Truman overstated the Soviet threat to the United States. In turn, his statements inspired a wave of hysterical anti-Communism throughout the country. Perhaps so. Others, however, would counter that this argument ignores the backlash that likely would have occurred if Greece, Turkey, and other countries had fallen within the Soviet orbit with no opposition from the United States.

Containment also called for extensive economic aid to assist the recovery of war-torn Western Europe. With many of the region's nations economically and politically unstable, the United States feared that local Communist parties, directed by Moscow, would capitalize on their wartime record of resistance to the Nazis and come to power. "The patient is sinking while the doctors deliberate," declared Secretary of State George C. Marshall. In mid-1947 Marshall asked troubled European nations to draw up a program "directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos."

The Soviets participated in the first planning meeting, then departed rather than share economic data and submit to Western controls on the expenditure of the aid. The remaining 16 nations hammered out a request that finally came to $17,000 million for a four?year period. In early 1948 Congress voted to fund the "Marshall Plan," which helped underwrite the economic resurgence of Western Europe. It is generally regarded as one of the most successful foreign policy initiatives in U.S. history.

Postwar Germany was a special problem. It had been divided into U.S., Soviet, British, and French zones of occupation, with the former German capital of Berlin (itself divided into four zones), near the center of the Soviet zone. When the Western powers announced their intention to create a consolidated federal state from their zones, Stalin responded. On June 24, 1948, Soviet forces blockaded Berlin, cutting off all road and rail access from the West.

American leaders feared that losing Berlin would be a prelude to losing Germany and subsequently all of Europe. Therefore, in a successful demonstration of Western resolve known as the Berlin Airlift, Allied air forces took to the sky, flying supplies into Berlin. U.S., French, and British planes delivered nearly 2,250,000 tons of goods, including food and coal. Stalin lifted the blockade after 231 days and 277,264 flights.

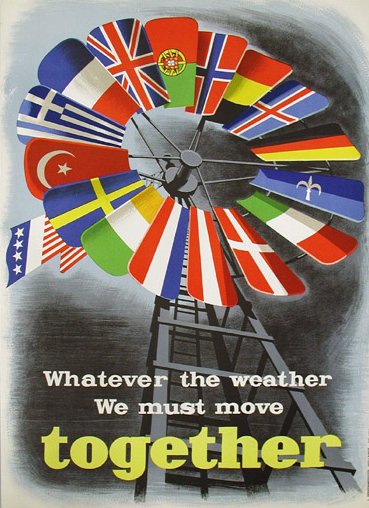

By then, Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and especially the Czech coup, had alarmed the Western Europeans. The result, initiated by the Europeans, was a military alliance to complement economic efforts at containment. The Norwegian historian Geir Lundestad has called it "empire by invitation." In 1949 the United States and 11 other countries established the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). An attack against one was to be considered an attack against all, to be met by appropriate force. NATO was the first peacetime "entangling alliance" with powers outside the Western hemisphere in American history.

The next year, the United States defined its defense aims clearly. The National Security Council (NSC) - the forum where the President, Cabinet officers, and other executive branch members consider national security and foreign affairs issues - undertook a full-fledged review of American foreign and defense policy. The resulting document, known as NSC-68, signaled a new direction in American security policy. Based on the assumption that "the Soviet Union was engaged in a fanatical effort to seize control of all governments wherever possible," the document committed America to assist allied nations anywhere in the world that seemed threatened by Soviet aggression. After the start of the Korean War, a reluctant Truman approved the document. The United States proceeded to increase defense spending dramatically.