World War I ended with an armistice signed November 11, 1918. The armistice was technically a truce between the warring nations, but in effect, it marked Germany's surrender.

Although the fighting had stopped, a formal treaty was still needed. The following January, the Paris Peace Conference was convened at Versailles, the former palace of the kings of France. Although nearly thirty nations participated, the representatives of Great Britain, France, the United States, and Italy -- known as the "Big Four" -- dominated the proceedings.

Negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference were not always easy. Great Britain, France, and Italy fought together during the First World War as Allied Powers. The United States, entered the war in April 1917 as an Associated Power, and while it fought on the side of the Allies, it was not bound to honor pre-existing agreements between the Allied powers. These agreements tended to focus on postwar redistribution of territories. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson strongly opposed many of these arrangements. Wilson also wanted -- and got -- a League of Nations that would serve as an international forum and work to prevent future wars.

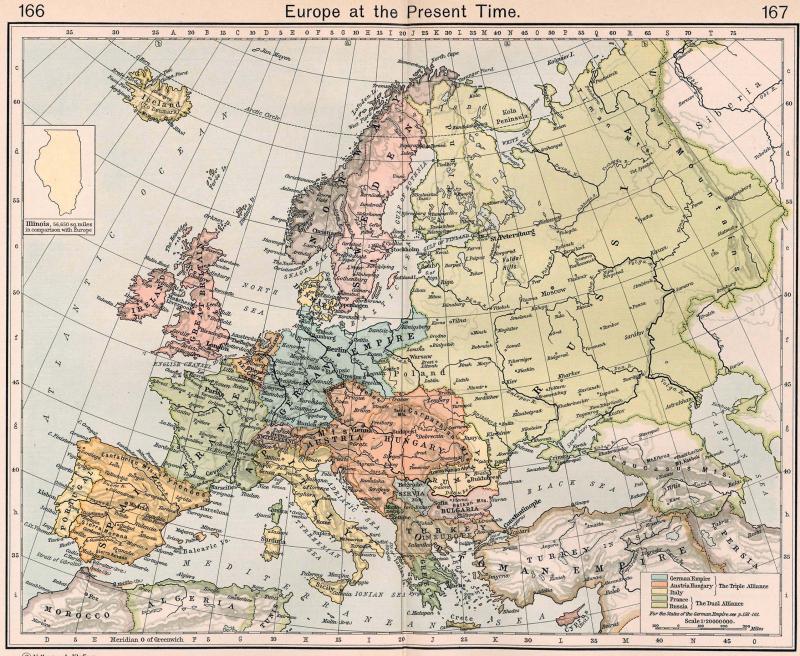

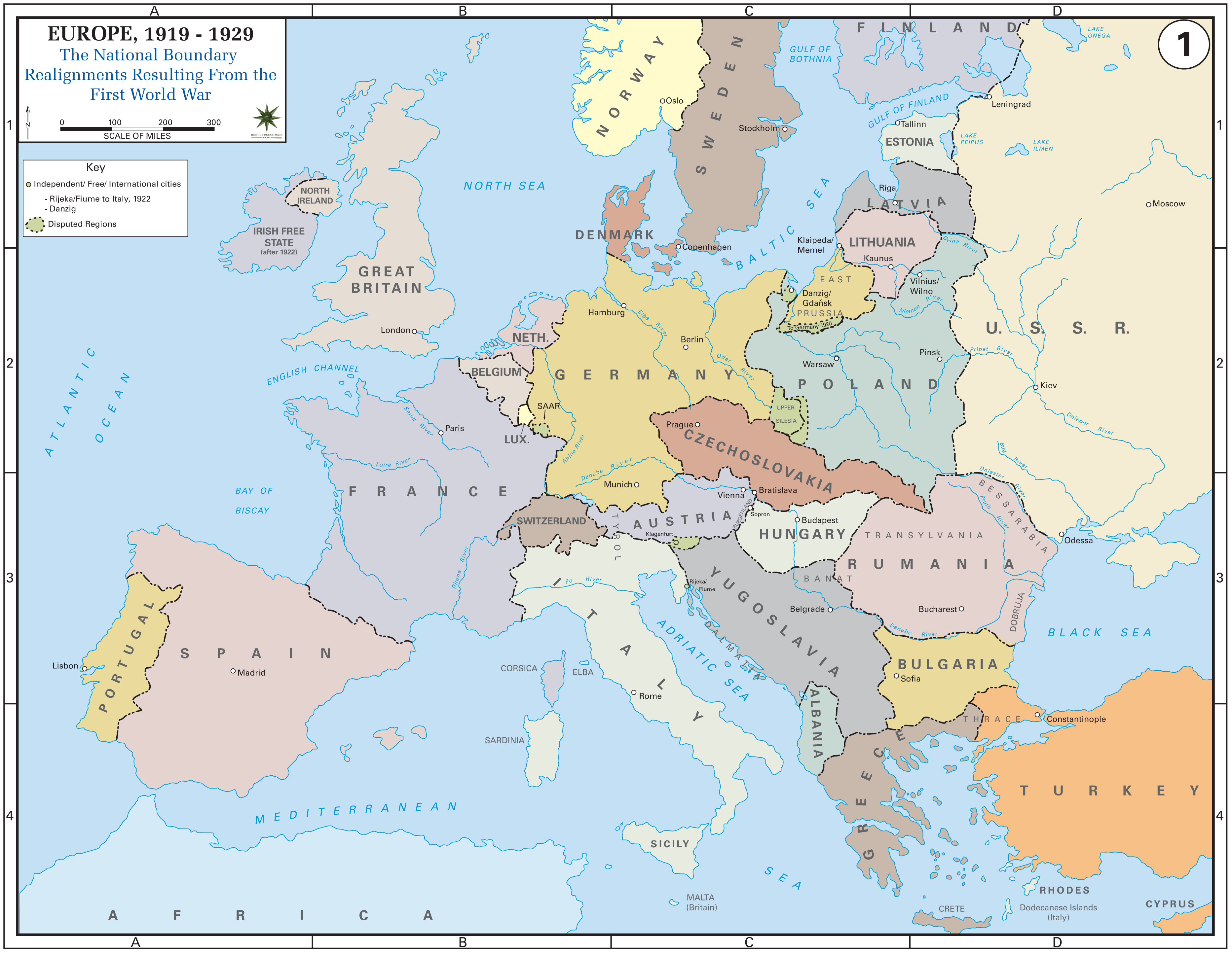

Treaty negotiations were also weakened by the absence of other important nations. Russia had fought as one of the Allies until December 1917, when its new Bolshevik government, formed after the Russian Revolution, withdrew from the war. The Allied Powers refused to recognize the new Bolshevik government and thus did not invite its representatives to the Peace Conference. The Allies also excluded the defeated Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria).

According to French and British wishes, Germany was subjected to strict punitive measures under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The new German government was required to surrender approximately 10 percent of its prewar territory in Europe and all of its overseas possessions. The harbor city of Danzig (now Gdansk) and the coal-rich Saarland were placed under the administration of the League of Nations, and France was allowed to exploit the economic resources of the Saarland until 1935. The German Army and Navy were limited in size. Kaiser Wilhelm II and a number of other high-ranking German officials were to be tried as war criminals. The Germans also accepted responsibility for the war and, as such, were required to pay financial reparations to the Allies -- an amount eventually set at 132 billion gold Reichmarks, or $32 billion, which came on top of an initial $5 billion payment.

While the Treaty of Versailles did not present a peace agreement that satisfied all parties concerned, by the time President Woodrow Wilson returned to the United States in July 1919, Americans overwhelmingly favored ratifying the treaty, including the Covenant of the League of Nations. Thirty-two state legislatures passed resolutions in support of the treaty. But there was intense opposition to it within the Senate, which had to ratify the treaty before it could become binding on the United States. The Treaty of Versailles fell seven votes short of ratification, and the United States signed a separate treaty with Germany in 1921. The U.S. never joined the League of Nations.

Many historians blame the Treaty of Versailles, in part, for the coming of World War II in Europe. Germans would grow to resent the harsh conditions imposed by the treaty. The reparations hurt the German economy and hastened the nation's plunge into the Great Depression. Wounded pride and a disastrous economy paved the way for the rise of the Nazi Party in the 1920s. The League of Nations, meanwhile, was not strong enough to keep the peace in Europe. Had the Treaty of Versailles been more generous to Germany, the Nazis might never have taken over. Had the treaty been much harsher, Germany could never have threatened other nations. As it was, the unfinished business of the "Great War" would have to be finished by an even greater one.