Throughout most of the 18th century the official view in Switzerland was that emigration was a crime against the fatherland equivalent to desertion. It deprived the home country of its labor force and soldiers for its defense.

Only at the very beginning of the century was one emigration scheme encouraged. In this instance the Council of Bern looked favorably on a scheme to petition the British Queen Anne to allow the establishment of a Swiss settlement of 400-500 persons in Pennsylvania or Virginia. The Council was hoping to use the project to get rid of undesirables: paupers who did not have citizens' rights and members of the Baptist, Anabaptist and Mennonite dissident religious sects.

In general, the British were as anxious to promote immigration to their American colonies as the Swiss were to prevent it, and for similar reasons: the need for manpower -- and for allies.

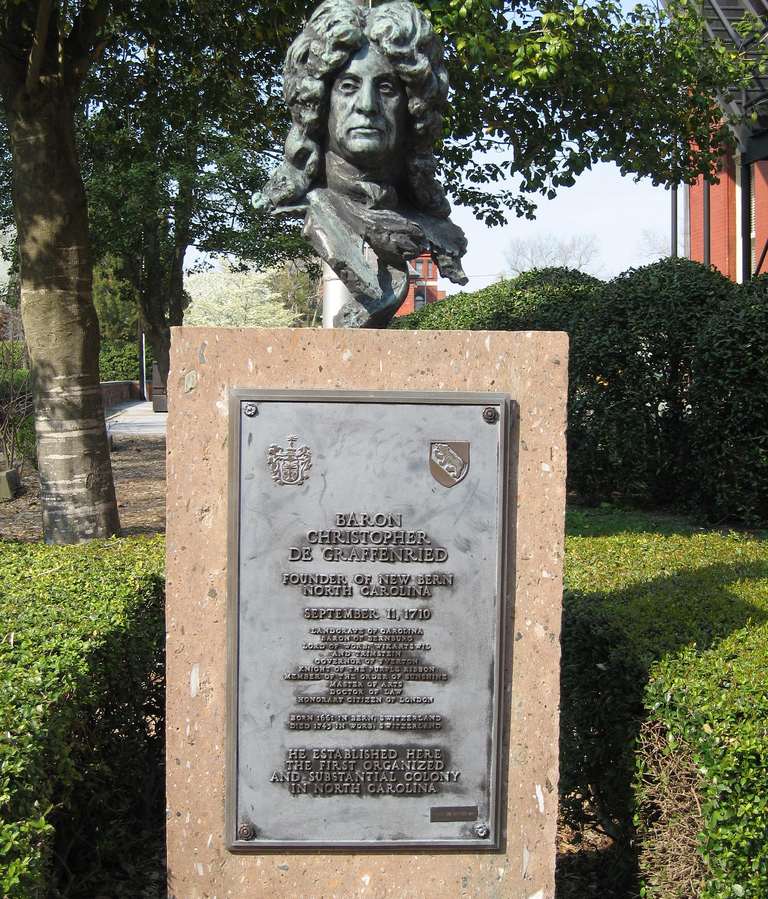

John Lawson, an Englishman who had travelled widely in Carolina between 1700-08, encouraged Baron Christoph von Graffenried in his plans to establish a Swiss settlement. Lawson wrote in his journal:

I believe, no Man that is in his Wits, and understands the Situation and Affairs of America, but will allow, nothing can be done of more security and advantage to the Crown and subjects of Great Britain, than to have our Frontiers secured by a Warlike People, and our Friends, as the Switzers are; especially when we have more Indians than we can civilize, and so many Christian Enemies lying on the back of us, that we do not know how long or short a time it may be, before they visit us.

Although the initial arrangements for this Swiss settlement failed, this was eventually the scheme which brought the colonists who populated New Bern. Von Graffenried, the founder of New Bern, and his followers were strongly influenced by a booklet first published in 1706 and written by a German pastor, Joshua Kochertal, vaunting the advantages of Carolina. Kochertal's praises were echoed by Lawson:

The Inhabitants of Carolina, thro' the Richness of the Soil, live an easy and pleasant life. The Land being of several sorts of Compost, some stiff, others light, some marl, others rich black Mould... one part bearing great Timbers, others being Savannas or natural Meads, where no trees grow for several Miles... yielding abundance of Herbage for Cattle, Sheep and Horse... [It is] a Country that, with moderate Industry, will afford all the Necessaries of Life.

But von Graffenried and his settlers found reality by no means lived up to Lawson's promises. The New Bern scheme, which collapsed after a few years, did not help the Council to get rid of undesirables, and Bern resorted again to strong discouragement if not outright prohibition of emigration.

The areas mainly affected by emigration were the Reformed cantons of Zurich, Bern and Basel. Strict edicts were issued in an attempt to stop it. Thus, the first edict issued in Zurich in 1734, forbade emigration to Carolina and prevented those wishing to leave from selling their property. Anyone distributing literature encouraging emigration was liable to punishment. This was followed up the next year by even more draconian measures: would-be emigrants were deprived of their citizenship and land rights forever, and anyone purchasing their property would be penalized.

At the same time, the authorities issued warnings about the dangers facing emigrants, both at sea and upon arrival and the hardships they might expect in the new land.

It seems that they did their best to intercept letters being brought from America: Any that spoke in favor of emigration were impounded and kept in the archives. Those that were unfavorable were often published.

The smith, Bachschlij Demuth, who left in 1734, succeeded in getting to Carolina with his wife and child, and has been able to send a letter brought by a man from Glarus, the contents of which were, that he is strong and can work well, can finally sustain himself in the new country, but that whoever is at home in his fatherland should remain there; he wished he had done so. — Report by Marx Thomann, Pastor at Wyla, April 1744

In 1744 Zurich attempted to draw up a census of emigrants: local authorities were ordered to provide lists of every man, woman and child who had left the country for either Carolina or Pennsylvania between 1734 and 1744. (These lists are a precious resource for genealogists.)

A tough emigration tax -- up to 10% -- was rigorously imposed in order to stem some of the outflow of money from the country; as a result some people tried to leave secretly to avoid having to pay.

Despite attempts to ban the exodus, most emigrants went with permission, however reluctantly granted, and often even with a certificate of good character from the pastor.

Quite a large proportion of emigrants were young people who had lost their fathers, and divorced and widowed people. Widows with numerous children were allowed to go, to stop them become a burden on the community. In some cases young people left home because of objections to their marriage, and got married on the journey.

Economic pressure was the main reason why people wanted to leave, not because they expected to grow rich, but in order to escape dire poverty.

A report by the Pastor of Dättlikon, March 1744, reads:

The paternal care of our gracious rulers is Christian, good, necessary, praiseworthy. But along with this, it is no less good and necessary, if one gives to the poor industrious but unemployed people enough work for their necessary sustenance, or otherwise gives them some needy assistance, then they would be glad to remain in their native land.

Emigrants sailed to both Pennsylvania and Carolina. Many of those who landed in Carolina subsequently made their way north to Pennsylvania. It was the Carolinas which received the most publicity in Switzerland: The only two independent Swiss colonies in North America were situated there. A couple of decades after the failure of New Bern, J.P. Purry (or Pury) in 1732 established the colony of Purrysburg in South Carolina. But migrants frequently moved from one area to another.

Records are too poor to give an accurate estimate of the number who emigrated from Switzerland during the 18th century; one estimate is that a total of about 25,000 left for America, with the greatest number going in the decade 1734-44.

Primary Source Citations:

Lawson, John. A New Voyage to Carolina. Edited by Hugh Talmage Lefler. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987.

Faust, Albert Bernhardt. 1920. Lists of Swiss Emigrants in the Eighteenth Century to the American Colonies. The Internet Archive. Vol. 1. Washington, D.C.: The National Genealogical Society. https://archive.org/details/listswissemigrant01fausrich/page/42.