In spite of their remarkable progress, late-19th century American farmers experienced recurring periods of hardship. Mechanical improvements greatly increased yield per hectare. The amount of land under cultivation grew rapidly throughout the second half of the century, as the railroads and the gradual displacement of the Plains Indians opened up new areas for western settlement. A similar expansion of agricultural lands in countries such as Canada, Argentina, and Australia compounded these problems in the international market, where much of U.S. agricultural production was now sold. Everywhere, heavy supply pushed the price of agricultural commodities downward.

Midwestern farmers were increasingly restive over what they considered excessive railroad freight rates to move their goods to market. They believed that the protective tariff, a subsidy to big business, drove up the price of their increasingly expensive equipment. Squeezed by low market prices and high costs, they resented ever-heavier debt loads and the banks that held their mortgages. Even the weather was hostile. During the late 1880s droughts devastated the western Great Plains and bankrupted thousands of settlers.

In the South, the end of slavery brought major changes. Much agricultural land was now worked by sharecroppers, tenants who gave up to half of their crop to a landowner for rent, seed, and essential supplies. An estimated 80 percent of the South's African-American farmers and 40 percent of its white ones lived under this debilitating system. Most were locked in a cycle of debt, from which the only hope of escape was increased planting. This led to the over-production of cotton and tobacco, and thus to declining prices and the further exhaustion of the soil.

The first organized effort to address general agricultural problems was by the Patrons of Husbandry, a farmer's group popularly known as the Grange movement. Launched in 1867 by employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Granges focused initially on social activities to counter the isolation most farm families encountered. Women's participation was actively encouraged. Spurred by the Panic of 1873, the Grange soon grew to 20,000 chapters and one-and-a-half million members.

The Granges set up their own marketing systems, stores, processing plants, factories, and cooperatives, but most ultimately failed. The movement also enjoyed some political success. During the 1870s, a few states passed "Granger laws," limiting railroad and warehouse fees.

By 1880 the Grange was in decline and being replaced by the Farmers' Alliances, which were similar in many respects but more overtly political. By 1890 the alliances, initially autonomous state organizations, had about 1.5 million members from New York to California. A parallel African-American group, the Colored Farmers National Alliance, claimed over a million members. Federating into two large Northern and Southern blocs, the alliances promoted elaborate economic programs to "unite the farmers of America for their protection against class legislation and the encroachments of concentrated capital."

By 1890 the level of agrarian distress, fueled by years of hardship and hostility toward the McKinley tariff, was at an all-time high. Working with sympathetic Democrats in the South or small third parties in the West, the Farmers' Alliances made a push for political power. A third political party, the People's (or Populist) Party, emerged. Never before in American politics had there been anything like the Populist fervor that swept the prairies and cotton lands. The elections of 1890 brought the new party into power in a dozen Southern and Western states, and sent a score of Populist senators and representatives to Congress.

The first Populist convention was in 1892. Delegates from farm, labor, and reform organizations met in Omaha, Nebraska, determined to overturn a U.S. political system they viewed as hopelessly corrupted by the industrial and financial trusts. Their platform stated:

We are met, in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and material ruin. Corruption dominates the ballot?box, the legislatures, the Congress, and touches even the ermine of the bench [courts].... From the same prolific womb of governmental injustice we breed the two great classes - tramps and millionaires.

The pragmatic portion of their platform called for the nationalization of the railroads; a low tariff; loans secured by non-perishable crops stored in government-owned warehouses; and, most explosively, currency inflation through Treasury purchase and the unlimited coinage of silver at the "traditional" ratio of 16 ounces of silver to one ounce of gold.

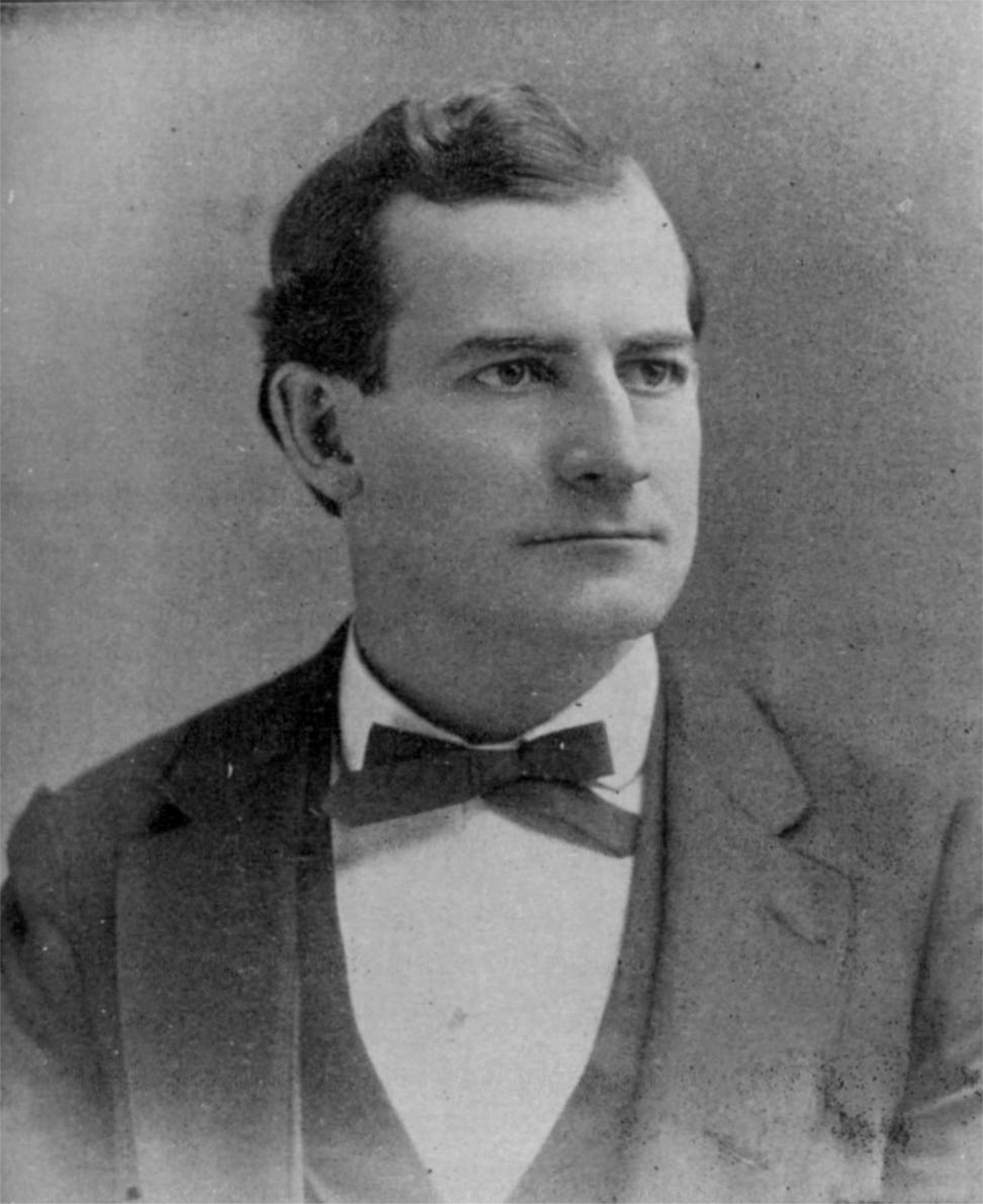

William Jennings Bryan was the choice of both Democrats and Populists for President in 1896 and 1900. He would run again as a Democrat in 1908, and would lose all three times.

The Populists showed impressive strength in the West and South, and their candidate for president polled more than a million votes. But the currency question soon overshadowed all other issues. Agrarian spokesmen, convinced that their troubles stemmed from a shortage of money in circulation, argued that increasing the volume of money would indirectly raise prices for farm products and drive up industrial wages, thus allowing debts to be paid with inflated currency. Conservative groups and the financial classes, on the other hand, responded that the 16:1 price ratio was nearly twice the market price for silver. A policy of unlimited purchase would denude the U.S. Treasury of all its gold holdings, sharply devalue the dollar, and destroy the purchasing power of the working and middle classes. Only the gold standard, they said, offered stability.

The financial panic of 1893 heightened the tension of this debate. Bank failures abounded in the South and Midwest; unemployment soared and crop prices fell badly. The crisis and President Grover Cleveland's defense of the gold standard sharply divided the Democratic Party. Democrats who were silver supporters went over to the Populists as the presidential elections of 1896 neared.

The Democratic convention that year was swayed by one of the most famous speeches in U.S. political history. Pleading with the convention not to "crucify mankind on a cross of gold," William Jennings Bryan, the young Nebraskan champion of silver, won the Democrats' presidential nomination. The Populists also endorsed Bryan.

In the epic contest that followed, Bryan carried almost all the Southern and Western states. But he lost the more populated, industrial North and East - and the election - to Republican candidate William McKinley.

The following year the country's finances began to improve, in part owing to the discovery of gold in Alaska and the Yukon. This provided a basis for a conservative expansion of the money supply. In 1898 the Spanish-American War drew the nation's attention further from Populist issues. Populism and the silver issue were dead. Many of the movement's other reform ideas, however, lived on.

Source Citation:

"An Outline of American History," United States Information Agency. https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/history/ch8.htm#agrarian