Five and a half years after the American Revolution began on April 19, 1775, on the village green at Lexington, Massachusetts, and nearly a thousand miles away, another group of Patriot militiamen mustered in North Carolina to fight for liberty. The Overmountain Men of 1780 gathered from the hills and valleys of western North Carolina, including today's northeast Tennessee, and from the Holston Valley of southwest Virginia. They joined forces with Patriot militiamen from the Yadkin Valley and Piedmont of North Carolina and from South Carolina and Georgia as well to surprise an invading British Army. During two weeks in the fall of 1780, this host of Southern, backcountry militiamen crossed the Appalachian mountain barrier and tracked down a detachment of the British Army under the command of General Lord Charles Cornwallis. After an all-night ride through a cold, rainy October darkness, these Patriot militiamen surrounded their Loyalist prey atop a small rise near the North Carolina-South Carolina line. In the battle that followed, this determined host of volunteer militiaman won a decisive victory that changed the course of the Revolutionary War. That fierce confrontation in the Carolina Piedmont became known as the Battle of Kings Mountain.

The war moves south

In 1780, the Revolutionary War moved to the Southern states. British authorities believed that many citizens in this region remained loyal to King George III and would rally to fight alongside an invading British force against the Patriot rebels. After Charles Town fell to the British invaders on May 12, General Sir Henry Clinton, commander of the British forces in the American Colonies, ordered his second-in-command, General Lord Charles Cornwallis, to march his army inland through the Carolinas and into Virginia. Clinton then returned to New York.

Cornwallis' army began moving northward across South Carolina toward the small community of Charlotte. Major Patrick Ferguson protected Cornwallis' left flank during the advance. Ferguson was a soldier's soldier, determined and disciplined. He was a brilliant military strategist, an experienced field commander, and was generally regarded as the best marksman in the British Army. As he swept through the backcountry of South Carolina, Ferguson had great success in recruiting American colonists to join his army as Loyalists. During his advance into the Upcountry area of South Carolina, however, Ferguson was continually harassed by North Carolina militia under the command of Colonel Isaac Shelby and Colonel Charles McDowell. Shelby's backwoods Patriots fought "Indian style," as it was called at the time, striking from ambush with war whoops and yells. They attacked and then retreated, forcing the British to pursue them into the woods in a running skirmish. Ferguson detested these ruffian militiamen whom he regarded as "backwater men," "barbarians," and "the dregs of mankind."

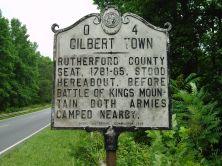

In mid-August, Major Ferguson pursued the rebel fighters, chasing Shelby and McDowell's men northward into North Carolina as far as Gilbert Town, a now-vanished community near today's Rutherfordton. Ferguson stopped his pursuit there, but Shelby's men and McDowell's men continued riding northwest. They retreated over the Blue Ridge and Appalachian Mountains to the safety of their homeland, the secluded overmountain region in the valleys of the Watauga, Nolichucky, and Holston Rivers.

The threat

From Gilbert Town, an aggravated Patrick Ferguson sent a message to the elusive Overmountain Men: "If you do not desist your opposition to the British Arms, I shall march this army over the mountains, hang your leaders, and lay waste your country with fire and sword."

Upon receiving Ferguson's threat to march into his community, terrorize his neighbors, and destroy their homes, Isaac Shelby wasted no time. He saddled his horse and rode hurriedly forty miles to the home of John Sevier, another prominent militia leader in the overmountain region. After lengthy consideration, the militia leaders decided it would be best if they crossed the mountains on their own terms and defeated Ferguson on the east side of the mountains. Thus did Patrick Ferguson, the would-be hunter, become the hunted.

The muster

The two leaders called for a mustering of militia units from throughout the overmountain region and beyond. They sent express riders north and east calling upon Arthur Campbell and William Campbell to muster Virginians from the Holston Valley and asking Colonel Benjamin Cleveland and Major Joseph Winston to muster men from the Yadkin Valley in Wilkes and Surry Counties. They called for a muster on September 25 at Sycamore Shoals, adjacent to Fort Watauga in today's Elizabethton, Tennessee.

Shelby brought 240 militiamen; Colonel Sevier brought a like number. Colonel William Campbell arrived with 400 Virginians, half from his cousin's command. These Virginians came on a two-day ride from their muster along Wolf Creek in today's Abingdon, Virginia. One hundred-sixty men from Burke County, under the command of Colonel McDowell, had taken refuge in the overmountain region after their earlier skirmishes with Ferguson. Growing day by day to some one thousand strong in number, the militiamen prepared to cross the mountains, committed in their pursuit of the man who had threatened to invade their homeland: Major Patrick Ferguson.

While the militiamen waited for all to arrive, they prepared themselves for the cross-country campaign and the battle they expected to find at the end of it. They tended their horses, mended clothing and equipment, and prepared food such as parched corn and beef jerky. The men cleaned their rifles and mined lead from the hillsides for making "shot" or ammunition. At Sycamore Shoals, they received from Mary Patton 500 pounds of gunpowder she had made at her own powder mill.

On September 26, the throng of a thousand militiamen headed south from Sycamore Shoals. Most of the men were on horseback, but some walked. This was not an army in the strictest sense of the word. All the men were volunteers; none was paid. Each expected to serve for only a few weeks before returning to his home to tend to his chores, his farming, and personal matters. The militia did not follow strict military protocol. They elected their commanders deciding among themselves whose leadership they would follow. The men were all skilled hunters and woodsmen. They were fighters, too, but they lacked the discipline of a military unit. For this last reason alone, the British military, the best army in the world, generally dismissed any threat from a fighting force composed of American volunteer militia.

The ascent

On the morning of the 27th, the militiaman began to ascend the mountain barrier. The men followed the Yellow Mountain Road, also known as Bright's Trace. It was little more than a horse path, most probably a well-trod buffalo trace later adopted by Indians as a footpath through the mountains. The militiamen followed it through the woods, ascending the steep slopes, riding and walking their horses to reach the gap in the mountain ridge.

When the militiamen arrived at the saddle in the ridge, at Yellow Mountain Gap (near today's Roan Mountain), they found themselves in a meadow standing in snow that was recalled as "shoe-mouth deep." The men fell into formation; the leaders took a head count. They discovered that two of Sevier's men were missing. The loyalty of these men to King George III was suspected by most. Many feared the two Tory traitors had deserted the campaign so they could run ahead and warn Major Ferguson that a host of Patriot militiamen was coming over the mountains to destroy his army. The band of militiamen had no choice but to continue. They descended the mountain a short distance and made camp along Roaring Creek.

The search

Over the next two days, the men proceeded across the plateau of the Blue Ridge Mountains arriving at Gillespie Gap along the edge of the Blue Ridge (the site of today's Museum of North Carolina Minerals on the Blue Ridge Parkway). From there they could see the Catawba Valley opening before them. Knowing that two good paths descended the face of the mountains, the leaders made a bold decision. They split their forces—a militarily risky move—to assure themselves that Ferguson and his army of Loyalists could not come up either path unimpeded and get around them into their homeland.

The two parties descended the face of the Blue Ridge separately and reunited two days later at Quaker Meadows (in today's Morganton). On the evening of September 30th, the reunited Overmountain Men were joined by 350 militiamen under Colonel Cleveland and Major Winston arriving after their four-day journey up the Yadkin River Valley from the mustering ground at Elk Creek (in today's Elkin).

The Patriot militiamen suspected that Ferguson and his army were in Gilbert Town. They proceeded south, but two days of rain forced them to make camp. On the morning of October 4, the men continued their march toward Gilbert Town but soon learned that Ferguson had already departed. The two deserters from Yellow Mountain Gap had indeed arrived at the Loyalist camp and told Ferguson of the Overmountain Men's pursuit. Ferguson immediately recognized his predicament and began retreating toward Charlotte, where Cornwallis's larger army was encamped.

On October 6, Ferguson sent a message to Cornwallis advising the General of his plans and asking for reinforcements. He wrote, "I am on my march towards you, by a road leading from Cherokee Ford, north of Kings Mountain. Three or four hundred good soldiers, part dragoons, would finish the business. Something must be done soon. This is their last push in the quarter, etc. - Patrick Ferguson."

The pursuit

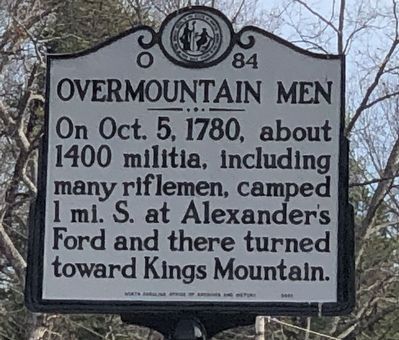

The Overmountain Men and the Carolina Patriots pursued Major Ferguson, relying on scouts to report his whereabouts. The force of Patriot militiamen rode hard all day October 6 to reach the Cowpens (on the site of the future Battle of Cowpens), where partisans from South Carolina joined them along with some thirty Georgia militiamen. The entire party of volunteer Patriot militiamen numbered near 1,800; none among them was a Continental soldier or officer.

Learning from scouts that Ferguson was near the safety of Charlotte, the Patriots knew they had to move quickly to overtake him. The leaders formed a smaller group, choosing from their ranks the 900 best marksmen mounted on the 900 best horses. At nine o'clock that evening, the chosen militia rode out from Cowpens into a cold October night. As a light rain began to fall, the men took off their hunting frocks and wrapped them around their rifles to keep the weapons dry and ready to fire. Although the men had already ridden some 21 miles that day, they had to cover 35 miles more through an all-night ride to overtake Ferguson. They slogged along muddy roads during a sleepless night, never stopping to eat or to rest. On the morning of October 7, they crossed the Broad River at Cherokee Ford. As the skies began to clear, the warming sun lifted the spirits of the men.

As the Patriots continued riding east, they learned from local residents that Ferguson was encamped atop Little Kings Mountain. It was a promontory rising about 60 feet above the surrounding terrain. The open area at the top was oblong, a few hundred yards in length and narrowing from 120 to 60 yards across. The sides were covered with trees and rocks. Ferguson had selected his campsite on top of the mountain believing that the high ground afforded him a military advantage should the Patriot militia catch up to him. He was later reported as having declared "he was on King's Mountain, that he was king of that mountain, and God Almighty could not drive him from it." His confidence in this strategy was soon to be tested.

The battle

The Patriots rode quietly toward the mountain. The rain-softened ground muffled the sound of their horses' hooves. No dust arose from the riders to warn of their coming. They neared the mountain undetected. The militiamen stopped in the woods, dismounted, and tied their horses. They proceeded quickly, attempting to surround the mountain before the sentries spied the advancing force. The Patriot militia continued to encircle the mountain as Ferguson, alerted to their presence, mounted his horse and signaled orders to his Loyalist troops with trills from his silver whistle. Ferguson was the only British soldier present on the plateau. All the other men under his command were Americans, colonists who had chosen to fight for their rights as Englishmen, as subjects of the King.

The Patriots advanced on all sides of Kings Mountain giving the enemy "Indian play," yelling loudly and firing from the cover of trees and rocks. This was American fighting American. Fortunate for the militiamen, the Loyalists shooting downhill with their Brown Bess muskets tended to shoot high and over the heads of the Patriots. Unfortunately for the militiamen, the Loyalists had bayonets. Upon Ferguson's orders, the Loyalist moved downhill in an organized attack with bayonets fixed. To the Patriot militiamen, it was a fearsome sight. The militiamen, needing a full minute to reload their long rifles, had no choice but to retreat in the face of a bayonet charge. When the Loyalists reached the bottom of the hill, they stopped pursuing the Patriots and returned to the top.

To their credit, the Patriot militia did not accept their retreat as defeat. All around the mountain, the Patriot militiamen, though repelled by bayonet charges, remounted their attack. Again they advanced up the faces of the mountain, taking deadly aim with their hunting rifles and claiming victim after victim. On their third assault, the Patriots took the crest of Kings Mountain. The Patriots pressed forward, encircling the Loyalists at the northeast end of the promontory. Ferguson, sensing defeat and knowing that he was about to be captured, rode in desperation toward the Patriot line hoping to escape by fighting through it. One seasoned militiaman took aim with his rifle and shot Ferguson out of his saddle. Ferguson's foot caught in the stirrup, and as his horse dragged the body of the hated British officer around the mountain top, at least six other Patriots fired into the body. Many more claimed to have done so.

With Ferguson dead, the Loyalist resistance quickly evaporated. Ferguson's second-in-command ordered his troops to surrender. Chaos and confusion reigned over the next few minutes as Patriot militiamen, recalling the brutality shown some of their comrades in past confrontations, fired into the ranks of unarmed Loyalists. Taking charge, Isaac Shelby regained control of the situation. The defeated Loyalists stacked their weapons and became prisoners of the Patriots. Through the remainder of the afternoon and evening, the men on both sides tended to their wounded and buried their dead in shallow graves. Ferguson's bold declaration never to leave Kings Mountain was fulfilled; he was buried on the battlefield not far from where he fell. His marked grave remains at Kings Mountain today.

The Patriots dared not linger long, as they feared that British reinforcements might appear at any moment. Unable to take along the captured supplies, the Patriots burned the wagons on top of the mountain. On the morning of October 8, the Patriots departed Kings Mountain with their prisoners.

The prisoners

The victorious Patriot militiamen, encumbered by their prisoners, made their way back toward Gilbert Town. Along the way, these undisciplined militiamen demanded retribution against some of the Loyalists they had captured. On October 14, the militiamen held a quick trial and condemned thirty of the men to death for atrocities committed against them, their friends, and kin. Nine Tories were hanged from a tree at Biggerstaff's plantation before Colonel Shelby stopped the slaughter.

Over the next several days, the Patriot militiamen disbanded, returning to their homes. The Overmountain Men re-crossed the Appalachian Mountains; Colonel Benjamin Cleveland and Major Joseph Winston took charge of the prisoners. Riding down the Yadkin Valley, the Patriots under their command delivered the captured Loyalists to the Moravian settlement at Bethabara, where the captives were imprisoned in a stockade.

Epilogue

Word of Ferguson's death and total defeat at Kings Mountain shocked and disheartened General Lord Charles Cornwallis. With the losses of one-third of his army and one of his most talented officers, Cornwallis delayed his planned advance northward from Charlotte into North Carolina. Abandoning their supply wagons mired in axle-deep mud and harassed by pursuing Patriot militia, the British army retreated to Winnsboro, South Carolina for a winter camp.

The Patriot victory at Kings Mountain had other effects as well. No longer could the British depend on American Loyalists in the Carolina Piedmont to flock eagerly to their standard. The Patriot spirit in the Carolinas was invigorated and the British Southern Campaign had been dealt a substantial blow. Though additional conflicts on other Carolina battlefields would be required to secure America's independence, the Battle of Kings Mountain was a turning point in the American Revolution. Forty-two years later, Thomas Jefferson recalled that battle as "the joyful annunciation of that turn of the tide of success which terminated the Revolutionary War." Indeed, Washington's Continental Army had been fighting valiantly for five-and-half years though without decisive effect; yet, only 12 months and 12 days after the Battle of Kings Mountain, General Cornwallis would surrender his British Army to General Washington at Yorktown, Virginia. The American Revolution would soon be over.

Image Credits:

William K.Boyd, "Battle of Kings Mountain" North Carolina Booklet: Great Events in North Carolina History, Vol. VIII, No. 4. (North Carolina Society, Daughters of the Revolution, April, 1909), 299-315. From North Carolina Digital Collections https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/north-carolina-booklet-great-... (accessed July 17, 2018).