Daniel Worth was a Methodist minister and Abolitionist born in a Quaker community in Guilford County. In 1823 Worth was in his early twenties when he and his family moved to Indiana. There he became a legislator, justice of the peace, Methodist minister, and the first president of the State Anti-Slavery Society of Indiana. In 1857 Worth returned to North Carolina as a missionary, and during this time, distributed Hinton Helper's The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet it along with other anti-slavery materials. After two years of missionary and abolitionist work, Worth was arrested in Guilford County for "circulating incendiary material against slavery." Below, historian John Bassett Spencer discusses the fallout of Worth's distribution of anti-slavery materials.

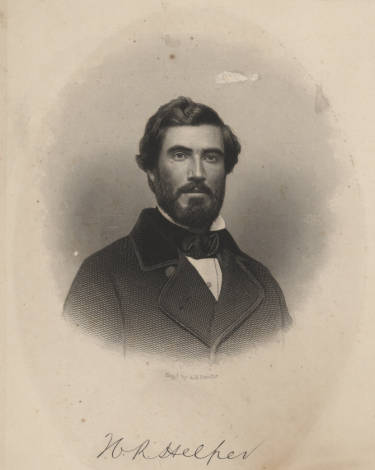

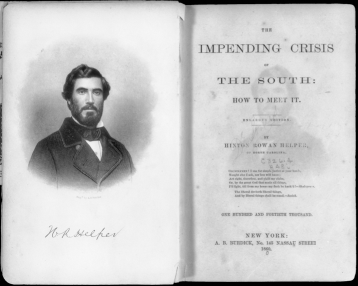

Mr. Helper must have known well when he wrote it Helper's book, The Impending Crisis of the South. that his book would receive little favor in the South. If he hoped otherwise, he was soon undeceived. The appearance of the work in the summer of 1857 was the signal for a flood of denunciation from that quarter. It was at once declared to come within the provision of the laws against the circulation of incendiary literature. To own a copy was against good taste, and traitorous to the interest of the South. In 1859 John A. Gilmer was the Whig candidate for the governorship in North Carolina. His opponents charged him with owning a copy of "The Impending Crisis." His friends replied by declaring that John W. Ellis, the Democratic candidate, had a copy. The Raleigh Standard, the leading Democratic paper of the State, indignantly denied the charge against Ellis. The truth of the matter, it said, was that in 1858, while Ellis was in New York, Mr. Helper, who had known him in North Carolina, called on him and later on sent a copy of the book. This Mr. Ellis threw out of the window. Sometime later Governor Ellis received another copy through the mails, and that he used for lighting his pipe.1 Making bonfires of the book was a mild feature of its reception in many parts of the South. The Northern papers reported that a number of persons were hanged or otherwise killed for having copies in their possession. The truth of the latter statement it has been impossible to prove....

Rev. Daniel Worth was a native of Guilford County, North Carolina, where, in early life, he had been a justice of the peace. Later he removed to Indiana, and at length became a member of the legislature in that State. Late in 1858 he returned to the neighborhood of his birthplace as a preacher in the Wesleyan Methodist Church. He preached the doctrine of his church, which was strongly anti-slavery, not without criticism, but, on account of the good feeling for his kinsmen, who were prominent people, without molestation. He planted a church at Sandy Ridge, near James-town, in Guilford County, and his postoffice was New Salem. His church had but few members. He aroused the opposition of many Quakers, most of whom were for non-intervention in regard to slavery. Worth thought they should be more positive in their opposition.

In December, 1859, after the Harper's Ferry affair, Mr. Worth was arrested on the charge of circulating Helper's book, and of preaching in a way "to make slaves and free negroes dissatisfied with their condition." He was required to give bond of $5000 for his appearance at the Superior Court the following spring, and of $5000 more to keep the peace. The first bond he gave. The second he thought unjust, and would not give. He was accordingly confined in the Greensboro jail throughout the winter. While there the sheriff of Randolph County arrested him on the same charge, and bound him over to the spring court. Other sheriffs waited around the place for him, fearing that he might be released and escape. While he was in prison five other men were arrested in Guilford and several more in Randolph, charged with having distributed Helper's book. One of these was Jesse Wheeler and another was an old man named Samuel Turner. All of these seem to have been natives who were converted by Mr. Worth's appeals. The Raleigh Standard bore witness to his success. It said that a few months before this occurrence only one copy of the New York Tribune came to Mr. Worth's postoffice, and that came to Mr. Worth himself. Now twelve copies were received there. To this it added: "We think it probable that one hundred to two hundred copies of the Tribune are circulated in this State, together with numerous abolition pamphlets from Indiana and Ohio." Wheeler alone was said to have distributed more than fifty copies of "The Impending Crisis." On his trial before the magistrate that committed him, Mr. Worth read from the book in order to show that it was not incendiary, a proceeding which the Raleigh Standard seems to have considered especially provoking.

The arrest occasioned great exemment in the vicinity, and for a time crowds surrounded the jail. A great crowd was in the courtroom when the case finally came to trial. The case was taken up and finished in one sitting. It was midnight when it went to the jury. In his charge the judge is reported to have said that "to sustain the allegation of seeking to exem the slaves and free colored people to discontent, it was not necessary to prove that the book had been read by or reemd to a free negro or slave, or that any such knew anything or any part of its contents.This is a key point: It was a crime not only to cause slaves to rebel or to run away, but also to do anything that might cause them to do so. That was the justification for limiting freedom of the press — that if Helper's book fell into the hands of a slave, it might incite him to violence."2 The jury returned at 4 A. M. with the verdict of "guilty." The jury, said the Fayetteville (N. C.) Presbyterian, was composed largely of non-slaveholders.3 The legal penalty was imprisonment for not less than one year and the pillory or the whipping-post, in the discretion of the judge. The court remitted the whipping on account of the age and calling of the prisoner, and sentenced him to one year's imprisonment. Many of the bystanders, said the New York Tribune, regretted the leniency of the court, and hoped that a more severe judge in another county might add the whipping. From this judgment the prisoner appealed to the Supreme Court of the State, and giving a bond of $3000, he was released. He at once repaired to New York city, where he made anti-slavery speeches and tried to raise money enough to repay the loss of his bondsmen. His bondsmen were his sympathizers, and the court records show that they were required to pay the forfeited bonds. On appeal, the judgment of the lower court was confirmed. It is likely that the authorities of Guilford were glad to be rid of him, so much attention was his case attracting in the North. He lived through the war that settled the question of slavery, and died within two years after its termination.4

Source Citation:

Bassett, John Spencer. "Anti-Slavery Leaders of North Carolina." Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science. Edited by Herbert B. Adams. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, June 1898. Published online by Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/bassett98/menu.html