On November 7, 1775, John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore, and Virginia's royal governor, declared martial law in Virginia by proclamation. Earlier in the year, he had begun a process of angering Virginia residents by seizing ammunition stores and threatening to impose martial law. In the wake of violent protests, he fled Williamsburg and took up residence aboard a British warship off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia where he remained for several months. Aboard the ship, he began a plan to recruit enslaved men to join the British army, further angering Virginia planters and farmers, as some black people began to run away from their enslavers to join.

The November 7 proclamation, in addition to declaring martial law, promised freedom to enslaved men who would leave their patriot enslavers to join the British cause. By the time of the proclamation, several hundred black people had already done so. The proclamation also declared revolutionaries to be traitors to Britain.

Estimates are that several hundred black men ultimately joined Dunmore's regiment, also known as Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment. Although many thousand more may have attempted escape.

The proclamation was published in The Virginia Gazette, and other newspapers throughout the colonies, where the reaction was severe.

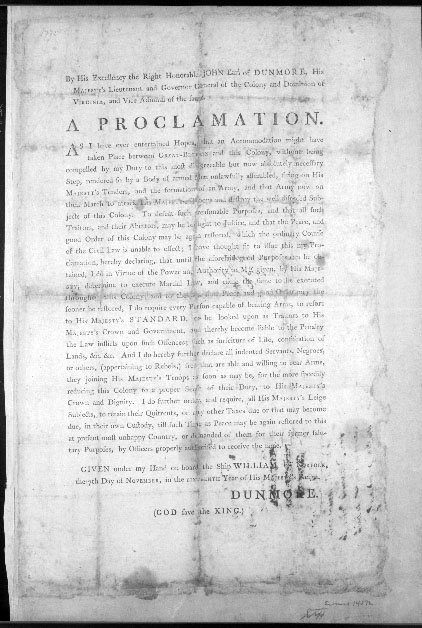

Read this transcription of Dunmore's Proclamation:

By His Excellency the Right Honorable JOHN Earl of DUNMORE, His MAJESTY'S Lieutenant and Governor General of the Colony and Dominion of VIRGINIA, and Vice Admiral of the same.

A proclamation

As I have ever entertained Hopes that an Accommodation might have taken Place between GREAT-BRITAIN and this colony, without being compelled by my Duty to this most disagreeable but now absolutely necessary Step, rendered so by a Body of armed Men unlawfully assembled, bring on His MAJESTY'S [Tenders], and the formation of an Army, and that Army now on their March to attack His MAJESTY'S troops and destroy the well disposed Subjects of this Colony. To defeat such unreasonable Purposes, and that all such Traitors, and their Abetters, may be brought to Justice, and that the Peace, and good Order of this Colony may be again restored, which the ordinary Course of the Civil Law is unable to effect; I have thought fit to issue this my Proclamation, hereby declaring, that until the aforefaid good Purposes can be obtained, I do in Virtue of the Power and Authority to ME given, by His MAJESTY, determine to execute Martial LawUnder martial law, the military takes over the system of justice and serves as police and courts. Martial law is most often imposed during time of war, when civilian authority breaks down. By the end of 1775, the royal government of the colonies had become completely powerless, and so the king authorized his governors to use the army to keep order. Typically under martial law people can be seized and held without trial, and they may be subject to quick trials and harsher penalties than under normal civilian justice., and cause the same to be executed throughout this Colony: and to the end that Peace and good Order may the sooner be [effected], [qtip:I do require every Person capable of bearing Arms, to [resort] to His MAJESTY'S STANDARD, or be looked upon as Traitors|His Majesty's standard was the flag carried by the king's troops. Dunmore is demanding that any man capable of bearing arms join the king's troops or be declared a traitor — in which case he would be subject to a penalty of death, and all his property and lands would be seized. Since the committees of safety had already branded any man a traitor who didn't join them, it's clear that there was no longer any room for compromise.] to His MAJESTY'S Crown and Government, and thereby become liable to the Penalty the Law inflicts upon such Offences; such as forfeiture of Life, confiscation of Lands, &c. &c. And I do hereby further declare all indentured Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY'S Troops as soon as may beUnder martial law, Dunmore could seize any property he thought the army needed — including slaves. (Interestingly, Abraham Lincoln would use the same logic in issuing the Emancipation Proclamation 87 years later: He had the legal authority to free the slaves only because their owners were in rebellion against the government.) Dunmore also wanted freed slaves and servants for his army, because he did not have enough troops to put down the rebellion., for the more speedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty, to His MAJESTY'S Leige Subjects, to retain their [Quitrents], or any other Taxes due or that may become due, in their own Custody, till such Time as Peace may be again restored to this at present most unhappy Country, or demanded of them for their former salutary Purposes, by Officers properly authorised to receive the same. GIVEN under my Hand on board the ship WILLIAM, off NORPOLE, the 7th Day of NOVEMBER, in the SIXTEENTH Year of His MAJESTY'S Reign.

DUNMORE.

(GOD save the KING.)