In his 1997 proclamation of a state "Tartan Day," Governor James Hunt stated that North Carolina had more people of Scottish heritage than any other state or country in the world (including Scotland). While Americans of Scottish descent do outnumber Scots in Scotland, which has a population of just over five million, California now claims the greatest number of residents of Scottish descent (partly by having attracted the most Scottish expatriates). Nonetheless, North Carolina does remain one of the states with the highest percentage of its population claiming trans-generational awareness of Scottish ancestry and, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2006 American Community Survey, is the state with the highest percentage of inhabitants self-identifying as Scots Irish. The greatest concentration of Scots Irish is in the west of the state, from Charlotte through the mountains.

Three Scottish ethnic groups settled in North Carolina with different cultural backgrounds and different reasons for immigrating. Lowland Scots tended to settle along the eastern seaboard with the English and to make their way into Appalachia for mercantile interests, particularly from Wilmington and Charleston. More Highlanders came to North Carolina than any other state and settled predominantly in the flat sandhills of the Cape Fear River Valley. The Scots Irish came to the mountains via the "Great Wagon Road" from Pennsylvania. Estimates vary, but at least a third of North Carolina’s mountain population was of Scots-Irish origin prior to the Civil War. They brought with them the folktales, ballads, farming strategies and some of the vernacular architectural traditions that would come to characterize the Southern Appalachian region. The ethnonym "Scotch-Irish" (Scots Irish) was first employed to distinguish Patriot Ulster Scots from Highland Scots (mostly Loyalists) and later to distinguish between Protestant Scots from Ulster and the Catholic "Famine Irish." The distinctiveness of these three ethnic groups is often elided today in contemporary heritage celebrations, as Scottish Americans commemorate ancestral Scots with the colorful material culture and expressive arts of Highland Scots. When North Carolina’s Scottish heritage revival developed in the 1950s, Hugh Morton had his camera poised and his photos chart the growth of a cultural movement across almost five decades.

The style of heritage events are largely creations of "Highlandism" a type of romanticism peculiar to Scotland that developed long after the ancestors of many of today’s Scottish Americans had emigrated. Sentimentalizing the Jacobite Lost Cause and the final defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s predominantly Highland army in 1746 at Culloden Moor, Highlandism led non-Gaelic-speaking Lowlanders who were not part of the clan system to forsake the ancient Highland/Lowland cultural divide and embrace bagpipes as a national symbol, don tartans and experiment with highly accessorized new versions of the kilt. Likewise, the landscapes of the Highlands, once considered "wild" and "ungodly," became the stereotypical image of Scotland. Today, even Scottish Americans of Lowland or Scots-Irish ancestry may happily compete in Highland Games, join societies modeled on the Highland clan system, and sport "clan tartans" (though the association of clan name and tartan pattern was largely devised in the nineteenth century).

Since the Scots Irish formed the largest Scottish presence in the mountains, the Highland Games at Grandfather Mountain in Linville might at first seem more "in" Appalachia than "of" it. Yet the conceiver of the event, Agnes MacRae Morton (mother of Hugh Morton), was a descendant of Highland Scots who immigrated to Wilmington in 1770. She co-founded the event with journalist Donald F. MacDonald in 1956, never expecting it to achieve the significance it has for Scottish Americans nationwide. MacDonald had recently attended Scotland’s most prestigious event, the Braemar Highland Gathering, which served as his model, and the Grandfather Games have since become known as "America’s Braemar." The first year’s Highland dancing competition drew only as many dancers as there were prizes and took place only because MacDonald himself performed a "Highland Fling," which Hugh Morton captured. The first event took place on August 19th, being a significant Jacobite anniversary (the 1745 raising of Prince Charlie’s standard at Glenfinnan), but eventually moved to the weekend following the Fourth of July. The Games now annually attract more than twenty thousand visitors to "MacRae Meadows" for four days of events, during which many North American Scottish clan associations hold their annual general meetings.

Citing the Robert Burns line "from scenes like these old Scotia’s grandeur springs," organizers attribute the event’s success to the Scotland-like setting and have adopted a tartan specifically created for the event with a green, grey, and blue sett (pattern) symbolic of the Grandfather Mountain landscape. Participants universally comment on the perceived resemblance of Grandfather Mountain to a Scotland romanticized in the nineteenth century as "the land of mountain and stream." In lieu of the ultimate pilgrimage to physically experience ancestral lands in Scotland, Scottish Americans claim to visit the Grandfather Highland Games to see "a wee bit of the Scottish Highlands" in America. Perching bagpipers on its highest peaks and photographing the mountain from the most spectacular vantage points with the event field and surrounding clan society tents nestled at its base, Morton capitalized on this appeal.

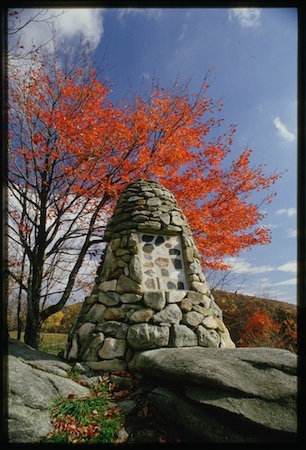

Enshrining this sense of clan lands at Linville, the Games field has accumulated its own toponyms: "pulpit rock" is the scene of the annual Sunday "kirkin of the tartan" (a church service); military re-enactors claim a portion of the camp grounds known as "Jacobite Glen" and musicians play day and night in wooded areas called the "Celtic Groves." Geopious descendants of the eighteenth-century Highland Scots who settled in the Cape Fear Valley erected memorial cairns at local churches to honor their immigrant ancestors and, in 1994, the tradition came to MacRae Meadows. The memorial cairn on Grandfather Mountain has inset panels with seventy-four polished stones contributed by as many clan societies, most brought from the clans’ homelands in Scotland.

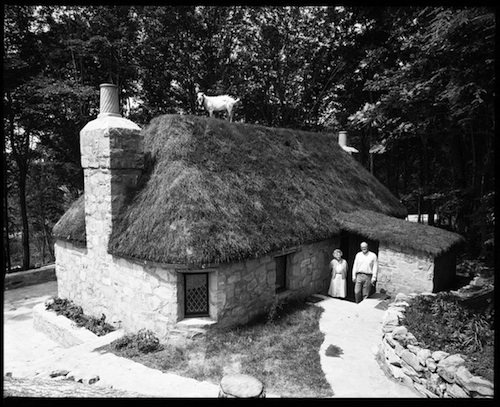

In the mid-1960s, efforts to instill a "sense of Scottish place" in the North Carolina mountains had included plans by Agnes MacRae Morton and her son Julian Morton to build a two thousand acre Scottish village at Linville. Never completed, "Invershiel" took its name from Clan MacRae territory in the Scottish Highlands, a place by Loch Duich and near the site of the decisive 1719 Jacobite battle in Glen Shiel. With the success of the Highland Games, Hugh Morton’s brother Julian spent ten years planning the development, and traveled to Scotland to design a delightful pastiche of architectural traditions from across the country. Buildings alternately combined sod and thatched roofs common across the Highlands and Aberdeenshire with chimney pots of the Lowlands and leaded glass windows copied from Stirling Castle, or employed crowstepped gables and pantiled roofs with "riggin" (ridge tiles) and walls constructed with local stone to imitate Scottish "rubble build."

The photo included here is of Agnes MacRae Morton’s "Croft House" (a farm house, if somewhat deluxe) and was one of several of Hugh Morton’s photos appearing in a 1967 Palm Beach Life feature on the Invershiel project. Most eastern Scottish burghs had "tolbooths" which were usually near a cross designating the local market area (the "mercat cross"). Tolls on market good were conveniently collected at these sites which also served as home to the burgh council, the sheriff court and the jail. At Linville today, the "tolbooth" from the Invershiel development is the centerpiece of the local shopping complex.

For an almost a half-century from the beginning of the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games into the twenty-first century, Hugh Morton documented the Scottish scene in and around Linville. Described as "a workaholic’s workaholic," Mr. Morton nevertheless always spared time to talk with researchers interested in the various subjects he had photographed and generously gave them permission to use his photos in too many books to mention. His archives will continue to be a rich resource for scholars. With particular regard to the Scottish-American community, his photography records both continuity and change in visions of "heritage" and also documents the creation of the Scottish place at MacRae Meadows — now considered a cultural omphalos for Scottish Americans from across the country.