By the late 1930s, the "good roads" of the 1920s were no longer enough to handle the traffic of American commerce and tourism. President Franklin Roosevelt believed that a network of transcontinental superhighways would create jobs for people out of work, and Congress funded a study. But with America on the verge of joining the war under way in Europe, the time for a massive highway program had not arrived.

Planning for postwar highways continued, and the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 authorized the construction of a 65,000-km (about 40,000 miles) "National System of Interstate Highways," designed to meet traffic needs twenty years after the date of construction, and

...so located as to connect by routes, as direct as practicable, the principal metropolitan areas, cities, and industrial centers, to serve the national defense, and to connect at suitable border points with routes of continental importance in the Dominion of Canada and the Republic of Mexico.

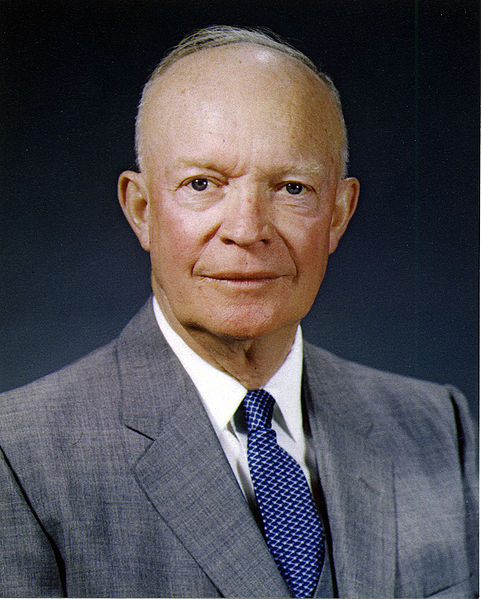

Construction of the interstate system moved slowly. Many states wanted to use their federal highway funds for local roads. Others complained that the standards of construction were too high. Also, by July 1950, the United States was again at war, this time in Korea, and the focus of the highway program shifted from civilian to military needs. When President Dwight D. Eisenhower took office in January 1953, the states had completed only about 6,500 miles of system improvements at a cost of $955 million -- half of which came from the federal government. Only a quarter of interstate roadways could handle even present traffic, let alone the increase expected over the next twenty years.

Long before taking office, Eisenhower had recognized the importance of highways. He first realized the value of good highways in 1919, when he participated in the U.S. Army's first transcontinental motor convoy from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco. On the way west, the convoy experienced all the woes known to motorists and then some -- an endless series of mechanical difficulties, vehicles stuck in mud or sand, trucks and other equipment crashing through wooden bridges, roads as slippery as ice or dusty or the consistency of "gumbo," and extremes of weather from desert heat to Rocky Mountain freezing.

During World War II, General Eisenhower saw the advantages Germany enjoyed because of the autobahn network. He also noted the enhanced mobility of the Allies when they fought their way into Germany.

As president, Eisenhower considered it important to "protect the vital interest of every citizen in a safe and adequate highway system." What was needed, the president believed, was a grand plan for a properly articulated system of highways. The president wanted a method of financing that would avoid debt. He wanted a cooperative alliance between state and federal officials to accomplish the federal part of the grand plan. And he wanted the federal government to cooperate with the states to develop a modern state highway system.

Congress defeated the president's initial proposals. On Jan. 5, 1956, in his State of the Union Address, the president renewed his call for a "modern, interstate highway system." That same month, Rep. George H. Fallon of Baltimore, Md., chairman of the Subcommittee on Roads in the House Committee on Public Works, introduced the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. It provided for a 66,000-km national system of interstate and defense highways to be built over thirteen years. This time, the federal government would pay 90 percent of the cost -- $25 billion.

The 1956 act called for uniform interstate design standards to accommodate traffic forecast for 1975. Access would be limited to interchanges (on- and off-ramps). Service stations and other commercial establishments were prohibited from the interstate right-of-way, in contrast to the franchise system used on toll roads. Toll roads, bridges, and tunnels could be included in the system if they met system standards and their inclusion promoted development of an integrated system. Two-lane segments, as well as at-grade intersections -- intersections where a stop sign or traffic light would be appropriate -- were permitted on lightly traveled segments. However, legislation passed in 1966 required all parts of the interstate highway system to be at least four lanes with no at-grade intersections regardless of traffic volume.

Eisenhower considered the Interstate Highway System his favorite domestic program. In his memoir, he wrote,

More than any single action by the government since the end of the war, this one would change the face of America.... Its impact on the American economy -- the jobs it would produce in manufacturing and construction, the rural areas it would open up -- was beyond calculation.

The next 50 years would be filled with unexpected engineering challenges, unanticipated controversies, and unforeseen funding difficulties. Nevertheless, the president's view would prove correct. The interstate system, and the federal-state partnership that built it, changed the face of America.