After the Civil War, a group of Black men in Raleigh were looking for a way to demonstrate the progress made by Black people in North Carolina since the emancipation of enslaved people in the state. In 1879 twenty-two of these men organized as the Colored Industrial Association of North Carolina. Their stated purpose was to improve and educate Black people in North Carolina and to demonstrate what newly freed people could accomplish. They decided to hold an "African American fair," similar to the State Fair that Raleigh had hosted since the 1850s. Charles N. Hunter, one of the founders of the group, called on "our farmers, mechanics, arti[s]ans, and educators, to come forward and place on exhibition their best productions."

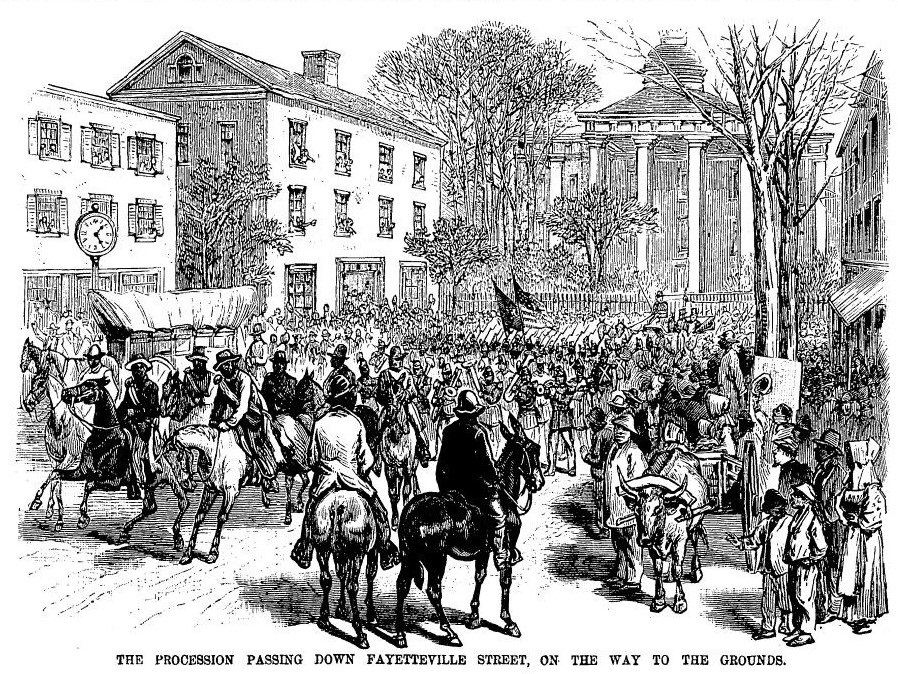

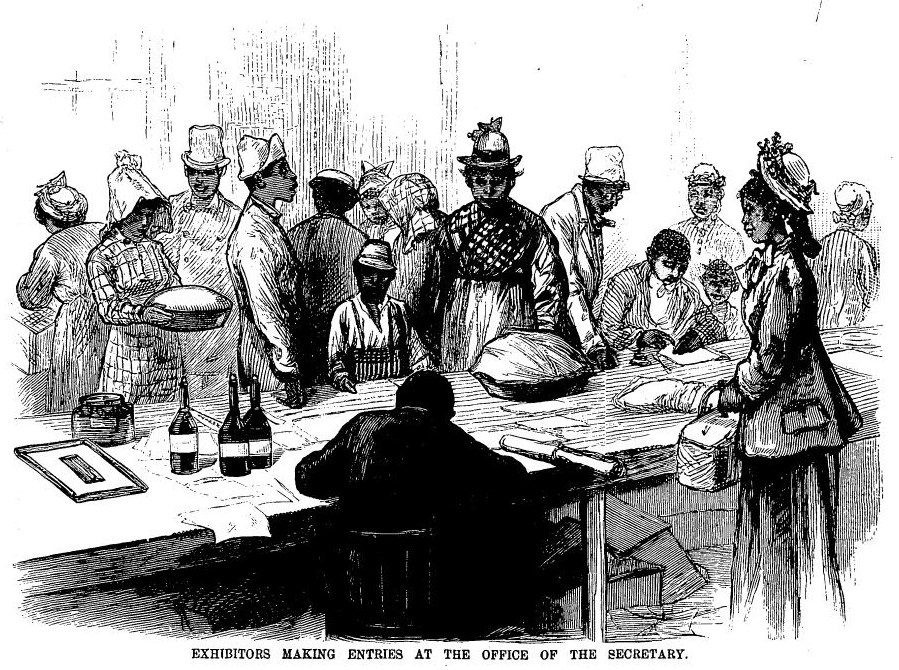

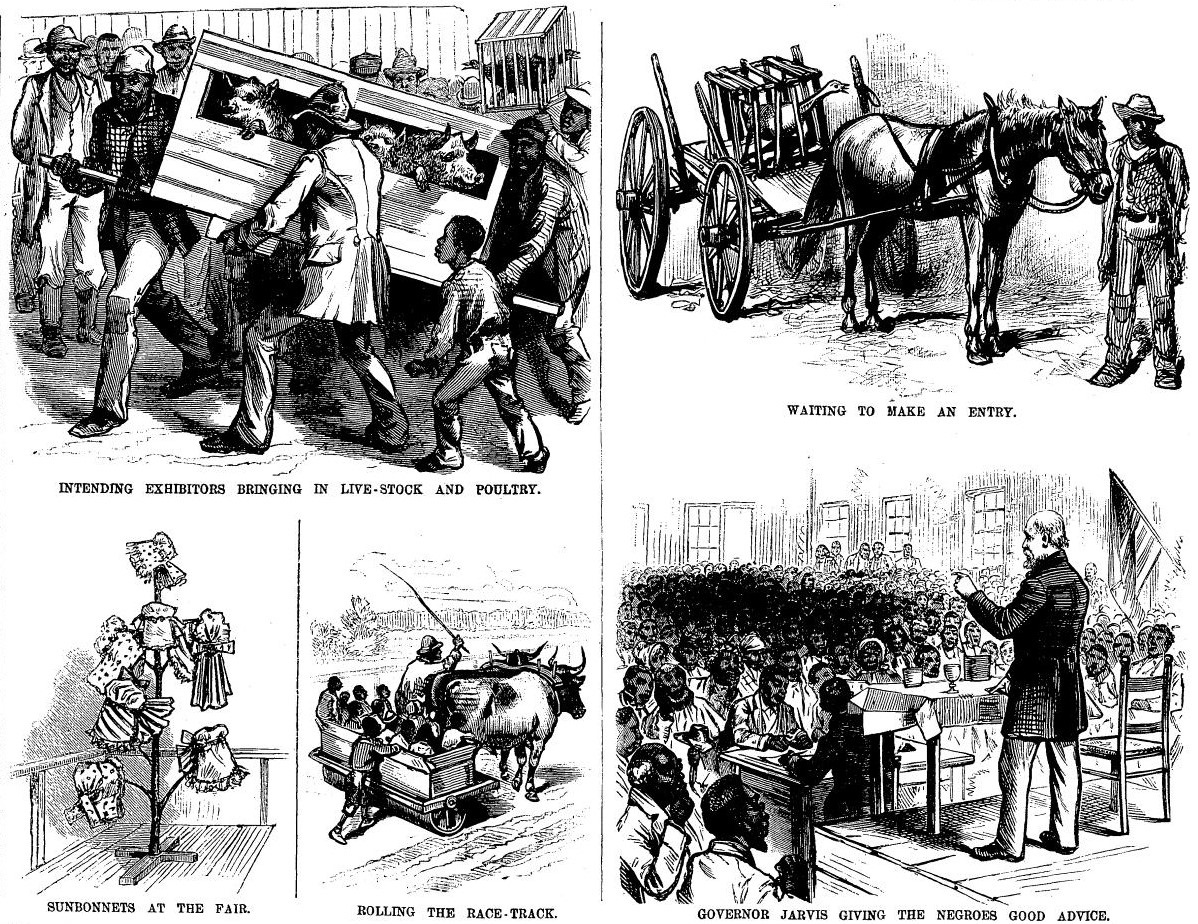

The association succeeded in organizing a fair in Raleigh during the month of November for a number of years in the late 1800s. The fair combined agricultural and industrial displays. Exhibitors displayed farm produce, crafts, and arts, including such items as poultry, needlework, quilts, and paintings. The fair gave prizes for the best products in a number of categories, including livestock, crops, poultry, horticulture, fine arts, mechanical arts (crafts), and carpentry. Authors read from their books, and Black-published newspapers were displayed. Prominent politicians and public figures, both black and white, made speeches during the fair. Parades and bands lent a festive air to the activities. Visitors traveled to the fair from across the state, and many railroads offered discounted rates to the fair’s exhibitors.

White-owned newspapers, such as the Raleigh News and Observer and the Charlotte Daily Chronicle, covered the fair. The latter praised the 1886 fair, reporting that "It was very successful and displayed great advancement in their [Black Americans’] industrial pursuits and many of the higher arts."

The Colored Industrial Association Fair did not become a financial success, however. When the fair was discontinued is unclear, although it lasted at least a decade. But the fair succeeded in other ways. Historian Frenise Logan has written that the fair promoted racial harmony, encouraged Black farmers to improve farm production, and presented the "educational, agricultural, and industrial resources of the Negro people of the State." Most of all, the fair showed the world how far Black people North Carolina had come in the decades immediately following their freedom.

Source Citation:

Sumner, Jim. "The African American State Fair." Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2002. https://archive.org/details/tarheeljuniorhis42tarh_0/page/26