By Kelly Agan, N.C. Government & Heritage Library, 2018

Two months after North Carolina's First Provincial Congress organized and adopted resolutions opposing the actions of Parliament, a group of North Carolina women made their own revolutionary political statement. It is one of the earliest examples in America of women organizing to influence laws, regulations, or customs. At the time, politics was considered a sphere for men only, and participation by women was considered improper.

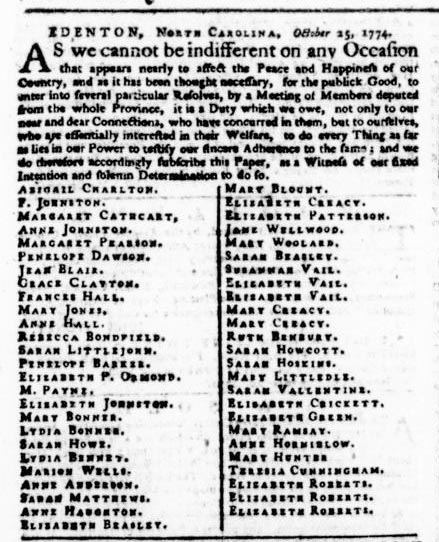

On October 25, 1774, fifty-one women in Edenton resolved to stop buying English imports and pledged to support the actions and resolutions of North Carolina's Provincial Congress. Their resolves were an historic step for colonists, who relied on tea, cloth and other goods that came from British trade. A few weeks later, their statement was printed in the November 3 edition of The Virginia Gazette, the local paper published in Williamsburg, Virginia. The names of the fifty-one women were published below their statement. And it did not take long for news of the event to reach a wider audience in London: in January of 1775, the statement published in the Gazette appeared in a London paper, the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser. And shortly after that, a London engraver created a cartoon satirizing the women for their patriotic action.

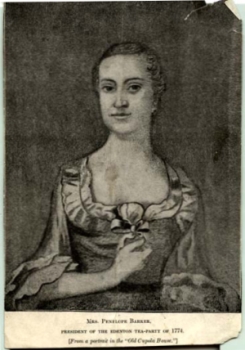

Historians credit one of the women, Penelope Barker, as a significant coordinator of the women's effort. Her husband, Thomas Barker, was an Edenton Lawyer and at one time a member of the Colonial Assembly.

In the late 19th century, a local Edenton historian re-invented the actions of the Edenton women as a "tea party". Since then it has remained known as the "Edenton Tea Party," although it very likely did not involve tea or a party. It was a bold demonstration of patriotism and a unique example of political organization by colonial women.

See the transcription of this statement by the women of Edenton, published in the November 3, 1774 edition of The Virginia Gazette below.

Edenton, North Carolina, Oct. 25, 1774.

As we cannot be indifferent on any occasion that appears nearly to affect the peace and happiness of our country, and as it has been thought necessary, for the public good, to enter into several particular resolvesIn August 1774, delegates from thirty of North Carolina's thirty-six counties and four towns met in New Bern. This First Provincial Congress, as it would be called, met for three days, during which it elected delegates to the Continental Congress that would meet in Philadelphia that fall and pledged to support its decisions. The Provincial Congress also supported the growing movement in the colonies to boycott British imports, called nonimportation, and created local "committees of safety" to enforce its acts. Although they had no legal standing, the delegates claimed to represent the people, and therefore to have more authority than the royal governor. Essentially, the Provincial Congress was the beginnings of a government in North Carolina separate from royal control. Two months later, the first Continental Congress made nonimportation more formal when its members agreed "to enter into a non-importation, non-consumption, and non-exportation agreement or association." This meant that they would not purchase any goods imported from Britain or from any British colonies in the West Indies, including not only tea but clothing, sugar, rum, and slaves. by a meeting of Members deputed from the whole Province, it is a duty which we owe, not only to our near and dear connections who have concurred in them, but to ourselves who are essentially interested in their welfareHere, the women note their duty to their "near and dear" -- that is, to their husbands who are active in the opposition to British authority. So while this petition was a bold step -- it was practically unheard of for women to sign a petition in the 1770s -- they still made it clear that they were supporting their husbands. They don't, in other words, seem to have been demanding any greater role in politics., to do every thing as far as lies in our power to testify our sincere adherence to the same; and we do therefore accordingly subscribe this paper, as a witness of our fixed intention and solemn determination to do so.

Abagail Charlton

Mary Blount

F. Johnstone

Elizabeth Creacy

Margaret Cathcart

Elizabeth Patterson

Anne Johnstone

Jane Wellwood

Margaret Pearson

Mary Woolard

Penelope Dawson

Sarah Beasley

Jean Blair

Susannah Vail

Grace Clayton

Elizabeth Vail

Frances Hall

Elizabeth Vail

Mary Jones

Mary Creacy

Anne Hall

Mary Creacy

Rebecca Bondfield

Ruth Benbury

Sarah Littlejohn

Sarah Howcott

Penelope BarkerToday historians credit Penelope Barker with organizing the women in their effort to write their own resolves. There is also an undocumented story that tells of another brave action she took during the Revolution. It tells that while her husband was away, British soldiers occupying Edenton took the horses from her stables. She grabbed her husband's sword, ran outside, and cut the reins from the hands of the officer, who told her that for such bravery she could keep her horses. Unfortunately, it's impossible to know whether this story -- like a lot of the really good stories from the American Revolution -- is true.

Sarah Hoskins

Elizabeth P. Ormond

Mary Littledle

M. Payne

Sarah Valentine

Elizabeth Johnston

Elizabeth Cricket

Mary Bonner

Elizabeth Green

Lydia Bonner

Mary Ramsay

Sarah Howe

Anne Horniblow

Lydia Bennet

Mary Hunter

Marion Wells

Tresia Cunningham

Anne Anderson

Elizabeth Roberts

Sarah Mathews

Elizabeth Roberts

Anne Haughton

Elizabeth Roberts

Elizabeth Beasly

Penelope Barker

Penelope Barker Edenton

Edenton