"Internal improvements" was a nineteenth-century term referring to investment in transportation projects such as roads, railroads, canals, harbors, and river navigation projects. These public works are an accepted responsibility of the modern state government, but in earlier times the concept of public funding for such projects was new and controversial. North Carolina was so isolated and poor in the early nineteenth century that it was derisively nicknamed the "Rip Van Winkle State." At alarming rates, emigrants fled its stagnant economy, worn-out farmland, poverty, and lack of opportunity. Among the state's greatest handicaps was inadequate transportation. Only a few rivers in the east were navigable, and even these were shallow and difficult to travel. The coast offered few good harbors, and roads, where they existed, were terrible. Under such conditions transportation was slow, inefficient, and so expensive that farmers could not afford to ship their produce more than a few miles.

Some state leaders, such as Governors Alexander Martin in 1791 and Nathaniel Alexander in 1806, asked the General Assembly for money to finance internal improvements. But many legislators and voters strongly opposed raising taxes or increasing government's involvement in internal improvements; for years, the state's role was limited to granting charters to private companies to operate toll bridges, canals, and navigation projects.

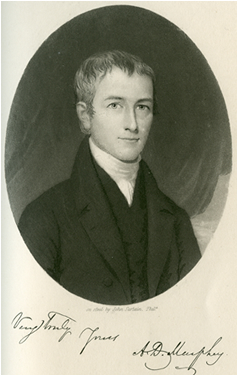

North Carolina's greatest advocate of internal improvements was state legislator and Caswell County native Archibald D. Murphey, who recommended that the government undertake ambitious transportation projects, develop market towns to build the state's economy, and drain swamps in the east to create new, fertile farmland. A revised version of his proposals to the General Assembly from 1815 to 1818 appeared in his 1819 Memoir on Internal Improvements. Murphey's plans included providing North Carolina with an extensive network of canals and navigable rivers linked by good roads. The new routes would be funneled into three systems: the Roanoke River and Albemarle Sound; the Tar and Neuse Rivers, which would have ocean access through Ocracoke Inlet; and a linking of the Yadkin and Catawba Rivers with the Cape Fear, to give western North Carolina access to the Atlantic. One of the state's great visionaries, Murphey did much to popularize internal improvements; however, he died before his ideas became reality.

In 1819 the work of Murphey and like-minded leaders persuaded the legislature to create a corporation, called the President and Directors of the Board of Internal Improvements, to manage a Fund for Internal Improvements, which would be a permanent source of revenue to underwrite internal improvements. The Board of Internal Improvements consisted of the governor (as an ex officio member) and six directors elected from each of the state's six judicial districts by a joint ballot of the two houses of the legislature. The duties of the board included appointing civil engineers for the state, subscribing to stock in public works as authorized by the General Assembly, recommending surveys and additional projects for legislative consideration, and reporting on the status of the Fund for Internal Improvements and internal improvements in which the state had an interest.

The General Assembly originally underwrote the Internal Improvements Fund using the proceeds from the sale of land formerly belonging to the Cherokee Indians. Federal treaties had extinguished title to approximately a million acres in the mountains in 1819, and the state proceeded to sell the land. In its 1821-22 session, the legislature, declaring that the fund was "entirely insufficient," augmented land sales with dividends from state-owned stock in the Bank of New Bern and the Bank of the Cape Fear.

Attention to internal improvements grew during the presidential election of 1824. Andrew Jackson's campaign platform included populist politics and the promise of internal improvements to less-developed states, like North Carolina. Jackson's platform resonated with voters in NC, as the state lagged behind its neighbors due to its lack of internal infrastructure

From the inception of the Internal Improvements Fund to the mid-1830s, the legislature used its moneys in conjunction with direct appropriations from the state treasury to promote various projects. Of $291,865 spent on internal improvements to 1836, $205,388 came from the fund. Engineering (surveys) amounted to $67,808; stock subscriptions in navigation companies (Roanoke, Cape Fear, Yadkin, Tar, Neuse, Catawba), the Clubfoot and Harlow Creek Canal Company, and turnpike companies (Buncombe and Plymouth), $142,900; direct appropriations for river improvements and highways, $59,157; and loans to support the Clubfoot and Harlow Creek Canal, Old Fort and Asheville Roads, and the Tennessee River Turnpike, $22,000.

Beyond financial assistance to the railroads and the usual expenses of the Board of Internal Improvements (travel for members of the board and salary of a clerk), relatively small sums of money from the fund were used to survey the Nags Head area on the Outer Banks and to finance road building and maintenance in the Mountain region. In 1847 the General Assembly, facing financial difficulties, decided to transfer the balance of the Internal Improvements Fund-$75,840-and all securities and sources of revenue for the fund to the public treasury. Thereafter most internal improvements were underwritten by direct appropriations.

Murphey's was not the only voice promoting reform. In 1828 Joseph Caldwell raised public interest in railroads through a series of newspaper essays, later republished as The Numbers of Carlton. The once nearly monolithic Republican Party split over several issues at the federal and state levels, including internal improvements. Progressive Republicans who supported internal improvements and other reforms formed the Whig Party around 1834-35. The Whigs adopted many of Murphey's ideas, making the party popular in western North Carolina, an underdeveloped region that hoped to benefit from new roads. The Albemarle Sound area, dependent on trade with Virginia, also favored the Whig policy of aiding transportation. By the mid-1830s, support for internal improvements was a crucial factor in the Whig ascendancy to the governorship and control of the General Assembly. Whig governors Edward B. Dudley, John Motley Morehead, and William A. Graham strongly advocated internal improvements.

By the advent of the Whig Party, the public was more interested in railroads than in water transportation. Railroads could reach anywhere in the state and did not depend on water flow and constant dredging, as did water routes. The first railroad company in North Carolina, the Wilmington & Raleigh, was founded in 1833, followed by the Raleigh & Gaston Railroad in 1835. The Whigs aided railroad construction by having the state buy railroad stock, and many other railroads were chartered in the antebellum period. Railroads would ultimately be the state's most successful internal improvement.

On regaining control of state government in the 1850s, the Democrats adopted many of the Whigs' progressive policies, including pushing for internal improvements. Newspaper editors like William W. Holden were very influential in getting the party to give up its opposition to state aid for transportation projects. Democratic initiatives in that area included greatly increased aid to railroads, including the east-west North Carolina Railroad, two-thirds of which was owned by the state. At this time Morehead City was founded to serve as an ocean port at the eastern terminus of the state railroad.

North Carolina's growth and prosperity in the 1850s were largely due to the increased ease of transportation and the growing economy produced by the internal improvements movement. Farmers profited by having cheap rail access to distant markets. Cities like Raleigh and New Bern, their growth fueled by railroad links, grew rapidly. This era ended with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. When internal improvements again became possible after the war, the state's poverty and conservative leadership prevented much direct state aid. But the public demand for reforms continued. In the late nineteenth century, the state, mainly by holding to a laissez-faire policy that protected business from taxes and regulations, helped railroads and other needed projects. As the twentieth century progressed, significant improvements such as the construction of state ports, reservoirs, highways, and public airports became a primary focus of state and county government. The term "internal improvements" eventually came to refer to these and other projects vital to the infrastructure of modern society.