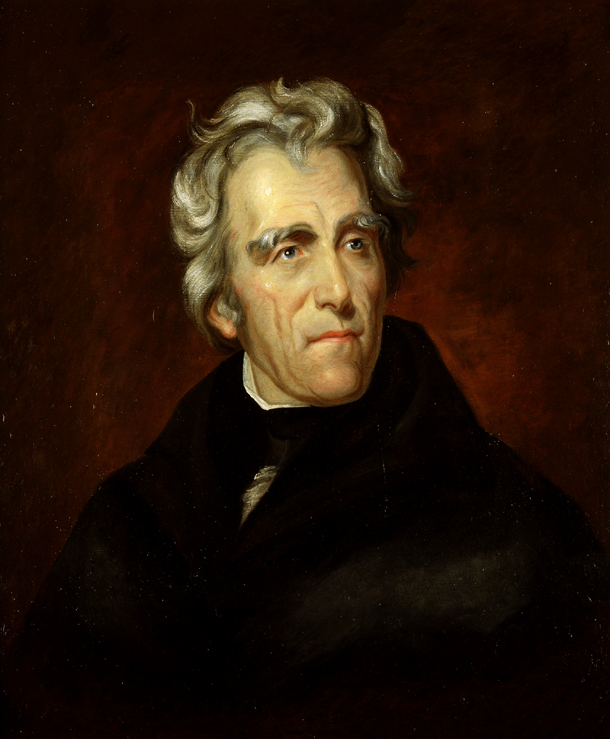

March 15, 1767 - June 8, 1845

Without union our independence and liberty would never have been achieved; without union they never can be maintained. ... The loss of liberty, of all good government, of peace, plenty, and happiness, must inevitably follow a dissolution of the Union.

---Andrew Jackson, Second Inaugural Address, 1833

Jump to: Childhood • The American Revolution • Public Career • Politics and Elections • The Presidency • Retirement

Childhood

Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States, was born in the Waxhaws area near the border between North and South Carolina on March 15, 1767. Jackson's parents lived in North Carolina but historians debate on which side of the state line the birth took place.

Jackson was the third child and third son of Scots-Irish parents. His father, also named Andrew, died as the result of a logging accident just a few weeks before the future president was born. Jackson's mother, Elizabeth ("Betty") Hutchison Jackson, was by all accounts a strong, independent woman. After her husband's death she raised her three sons at the South Carolina home of one of her sisters.

The American Revolution

The Declaration of Independence was signed when young Andrew was nine years old and at thirteen he joined the Continental Army as a courier. The Revolution took a toll on the Jackson family. All three boys saw active service. One of Andrew's older brothers, Hugh, died after the Battle of Stono Ferry, South Carolina in 1779, and two years later Andrew and his other brother Robert were taken prisoner for a few weeks in April 1781. While they were captives a British officer ordered them to clean his boots. The boys refused, the officer struck them with his sword and Andrew's hand was cut to the bone. Because of his ill treatment Jackson harbored a bitter resentment towards the British until his death.

Both brothers contracted smallpox during their imprisonment and Robert was dead within days of their release. Later that year Betty Jackson went to Charleston to nurse American prisoners of war. Shortly after she arrived Mrs. Jackson fell ill with either ship fever or cholera and died. Andrew found himself an orphan and an only child at fourteen. Jackson spent most of the next year and a half living with relatives and for six of those months was apprenticed to a saddle maker.

Public Career

After the war Jackson taught school briefly, but he didn't like it and decided to practice law instead. In 1784, when he was seventeen, he went to Salisbury, North Carolina where he studied law for several years. He was admitted to the North Carolina Bar in September 1787 and the following spring began his public career with an appointment as prosecuting officer for the Superior Court in Nashville, Tennessee, which at that time was a part of the Western District of North Carolina.

In June 1796 Tennessee was separated from North Carolina and admitted to the Union as the sixteenth state. Jackson was soon afterward elected the new state's first congressman. The following year the Tennessee legislature elected him a U.S. senator, but he held his senatorial seat for only one session before resigning. After his resignation Jackson came home and served for six years as a judge on the Tennessee Supreme Court.

Jackson's military career, which had begun in the Revolution, continued in 1802 when he was elected major general of the Tennessee militia. Ten years later Tennessee Governor Willie Blount (of the North Carolina Blount family) gave him the rank of major general of U.S. forces. In 1814, after several devastating campaigns against Native Americans in the Creek War, he was finally promoted to major general in the regular army. Jackson also later led troops during the First Seminole War in Florida.

General Jackson emerged a national hero from the War of 1812, primarily because of his decisive defeat of the British at the Battle of New Orleans. It was during this period he earned his nickname of "Old Hickory." Jackson had been ordered to march his Tennessee troops to Natchez, Mississippi. When he got there he was told to disband his men because they were unneeded. General Jackson refused and marched them back to Tennessee. Because of his strict discipline on that march his men began to say he was as tough as hickory and the nickname stuck.

Politics and Elections

All his life Jackson was a loyal friend and a fierce enemy. This was never more true than during his years in politics at the national level beginning with the 1824 presidential election.

Jacksonians often referred to the 1824 election as the "Stolen Election" because while Jackson swept the popular vote hands down, he did not have enough electoral votes to automatically win the presidency. Therefore the election had to be decided by the House of Representatives.

Jackson's opponents were Henry Clay of Kentucky, John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, and William H. Crawford of Georgia who were respectively speaker of the house, secretary of state, and secretary of the treasury. Adams was horrified at the thought of Jackson becoming president. The patrician New Englander thought this parvenu from the west was a badly educated bumpkin with little preparation for high office. Because Clay's opinion of Jackson was similar, the Kentuckian threw his support to Adams on the first ballot and Adams was elected. Jackson never forgave either one of them, especially after Adams named Clay his secretary of state in what seemed to be a payoff for Clay's votes.

In the years leading up to the 1828 election Jackson and his followers continually criticized the Adams administration. Jackson took the position he was the people's candidate and never lost an opportunity to point out that the people's choice in 1824 had been disregarded by the elite. This tactic proved successful and Jackson defeated Adams in the 1828 election and four years later defeated Clay in the election of 1832.

Loss of the "Stolen Election" was not the only thing Jackson held against Adams. During the 1828 campaign the Adams camp charged Jackson and his wife with adultery. The claims grew out of naivete on the Jacksons' part. Rachel Donelson had a first, unhappy marriage with Lewis Robards. In 1790 the Kentucky legislature passed a resolution granting Robards permission to sue for divorce, though he did not do so at the time.

Andrew and Rachel confused the permission to sue with an actual declaration of divorce. They married in 1791, not realizing Rachel was still legally married. Robards finally sued for divorce in 1793 citing Rachel's "adultery" with Jackson. The Jacksons remarried in 1794, but the embarrassing and often malicious gossip persisted. Rachel Jackson died a few weeks before her husband's inauguration and Jackson blamed her early death on stress caused by the public discussion of their supposed immorality during the campaign.

The Presidency

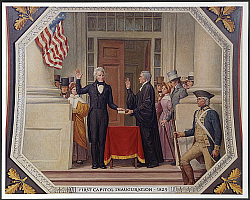

Andrew Jackson may have been our seventh president, but he was first in many ways. He was the first populist president who did not come from the aristocracy, he was the first to have his vice-president resign (John C. Calhoun), he was the first to marry a divorcee, he was the first to be nominated at a national convention (his second term), the first to use an informal "Kitchen Cabinet" of advisers, and the first president to use the "pocket veto" to kill a congressional bill (legislation fails to become law if Congress adjourns and the president has not signed the bill in question).

Jackson believed in a strong presidency and he vetoed a dozen pieces of legislation, more than the first six presidents put together. Jackson also believed in a strong Union and this belief brought him into open opposition with Southern legislators, especially those from South Carolina. South Carolina thought the 1832 tariff signed by President Jackson was much too high. In retaliation, the South Carolina legislature passed an Ordinance of Nullification, which rejected the tariff and declared the tariff invalid in South Carolina. Jackson , always a strong Unionist, issued a presidential proclamation against South Carolina. On the whole Congress supported Jackson's position on the issue and a compromise tariff was passed in 1833. The immediate crisis passed, but the incident was a precursor of the positions that would lead almost thirty years later to the War Between the States.

Another major issue during Jackson's presidency was his refusal to sanction the recharter of the Bank of the United States. Jackson thought Congress had not had the authority to create the Bank in the first place, but he also viewed the Bank as operating for the primary benefit of the upper classes at the expense of working people. Jackson used one of his dozen vetoes, and the Bank's congressional supporters did not have enough votes to override him. The Bank ceased to exist when its charter expired in 1836, but even before that date the president had weakened it considerably by withdrawing millions of dollars of federal funds.

Jackson's record regarding Native Americans was not good. He led troops against them in both the Creek War and the First Seminole War and during his first administration the Indian Removal Act was passed in 1830. The act offered the Indians land west of the Mississippi in return for evacuation of their tribal homes in the east. About 100 million acres of traditional Indian lands were cleared under this law.

Two years later Jackson did nothing to make Georgia abide by the Supreme Court's ruling in Worcester vs. Georgia in which the Court found that the State of Georgia did not have any jurisdiction over the Cherokees. Georgia ignored the Court's decision and so did Andrew Jackson. In 1838-1839 Georgia evicted the Cherokees and forced them to march west. About twenty-five percent of the Indians were dead before they reached their new lands in Oklahoma. The Indians refer to this march as the "Trail of Tears" and even though it took place after Jackson's presidency, the roots of the march can be found in Jackson's failure to uphold the legal rights of Native Americans during his administration.

During Jackson's presidential years two states were admitted to the Union (Arkansas in 1836 and Michigan in 1837) and the rulings of Roger Taney, one of his Supreme Court appointments, had an impact on American life long after Jackson's retirement. In 1836 Taney succeeded John Marshall as chief justice. One of Taney's early rulings gave permission for states to restrict immigration, while another destroyed a transportation monopoly in Massachusetts, establishing for the first time the principle in U.S. law that the public good is superior to private rights. But Taney is best known for his pro-slavery position in the Dred Scott case in 1857. Chief Justice Taney authored the majority opinion which refused to recognize that Congress had the authority to ban slavery in territory areas. In addition he said Blacks were "inferior" beings who had "no rights which the white man was bound to respect."

Retirement

Jackson's health was never good and there were times during his presidency when it seemed he would not live to complete his term. But complete it he did and in 1837 retired to his home near Nashville which he and Rachel had named The Hermitage. When the Hermitage was first built it was little more than a small cabin, but by Jackson's retirement it had been expanded, remodeled, and rebuilt into a spacious plantation house. The Hermitage was operated and maintained by laborers enslaved by the Jackson family. In January 1829, ninety-five people were enumerated as enslaved by Jackson. A year later, when Jackson was sitting as President, fourteen people were listed on the 1830 census with Jackson as their enslaver at the White House.

Jackson remained a force in politics in his latter years. For example it was very much Jackson's behind the scenes maneuvering which secured the presidency for his successor Martin Van Buren and in 1840 he actively campaigned for Van Buren in Van Buren's unsuccessful candidacy for re-election. Jackson also worked for the annexation of Texas and remained loyal to future President James K. Polk (another North Carolina native). Polk had been one of Jackson's strongest supporters in Congress as Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee.

In his last few years Jackson's health deteriorated badly and he died at the Hermitage on June 8, 1845.

Andrew and Rachel Jackson did not have any children of their own, but adopted one of Rachel's nephews and gave him the name of Andrew Jackson, Jr. Jackson willed the Hermitage to Andrew Jr., but young Jackson's debts forced the sale of the property to the State of Tennessee in 1886. The Hermitage is today open to the public as an historic site.