See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001, Rural Life in NC for K-8 Students

Isolation and Cultivating the Land

Overwhelmingly rural, North Carolinians were isolated from the world around them, as well as each other, by geographical barriers, limited means of transportation, and their own independent spirit. However "backward" and "indolent," most Tar Heels had a more discerning, if not more favorable, view of their lifestyle and themselves. Times were hard; there is no doubt. Days were long and rewards were slight. Yet an increasing number of Carolinians had succeeded in purchasing their own farms. And, as the Fayetteville Observer, in 1837, proudly pointed out: "The great mass of our population is composed of people who cultivate their own soil, owe no debt, and live within their means. It is true we have no overgrown fortunes, but it is also true that we have few beggars."

Undoubtedly the most important bond among those who composed the rural community was their common interest in cultivating the land. Agriculture was their way of life, and it informed their every thought and action. The farm, whether 10 acres or 10,000, was the basic unit of economic production and social organization. It was there that the vast majority of Carolinians could be found—working their fields, preparing their meals, rearing their children, and living out their lives.

Plantation Life

In North Carolina the "Old South" of fiction and film did not exist. There were vast plantations and belles, white-columned mansions and "poor white trash." But the Old North State in the antebellum period was a land of yeoman farmers rather than gallant planters, of free blacks as well as slaves, and of corn and livestock in addition to tobacco and cotton. Though there were some 300 plantations of 1,000 acres or more in the state in 1860, there were more than 46,000 farms of less than 100 acres. If the economic, political, and social influence of the larger planters outweighed their numerical proportion, in terms of lifestyle they represented an anomaly. Remodeled in 1826 from a 1785 dwelling of planter Henry Lane, the Mordecai House features the Greek Revival style of many plantation houses.

The Planters

Somerset Place State Historic Site in Washington County offers a provocative glimpse of life among the planter elite in the antebellum South. Begun in the late eighteenth century, the plantation was largely the creation of Josiah Collins of Edenton, who had emigrated from England in 1773 and made a fortune as a merchant during the American Revolution. Along with two partners whom he later forced to sell out, Collins formed the Lake Company to develop the desolate and, at the time, worthless swamplands bordering Lake Phelps. The company arranged for a direct shipment from Africa of eighty slaves, who were put to work digging a canal twenty feet wide from the lake to the Scuppernong River, a distance of six miles. Upon completion of the three-year project, a large estate was drained and cleared, grist- and sawmills were constructed along the canal, and the company began gradually divesting itself of the 100,000 acres it had acquired in the area.

The Bennehan and Cameron families, who were linked by business partnership as well as marriage, were among the wealthiest in the state. Paul C. Cameron, on whom the management of their combined holdings devolved in the decades prior to the Civil War, was known for his conscientiousness as a planter and his willingness to adopt innovative agricultural techniques. But the primary source of success for any planter, whether a Cameron in the Carolina Piedmont or a Collins on the Coastal Plain, was the industry and labor provided by the plantation workforce.

Enslaved Peoples

The material remains of slave life in North Carolina are all but gone. Yet on a gentle knoll in Durham County, surrounded by the fields and forests known as Horton Grove, several weatherworn structures stand as a reminder of the vital culture that enslaved persons developed in the state. Now part of Historic Stagville, Horton Grove in the mid-nineteenth century was a productive component of the vast estate owned by the powerful Bennehan and Cameron families. The four substantial but decaying dwellings, which can be visited at the site, housed a portion of the hundreds of slaves who worked the Bennehan-Cameron properties and formed a cohesive community with roots in the colonial period and descendants in the region to this day.

The field hands on the Bennehan-Cameron properties in the 1850s were responsible for producing vast quantities of tobacco, corn, and wheat for the market in addition to growing cotton, oats, rye, and flax largely for plantation use. At the same time, Bennehan-Cameron slaves were charged with the care of several hundred swine, sheep, and beef cattle, as well as numerous horses, mules, and other livestock essential to the estate's operation.

The material quality of life for slaves in antebellum North Carolina was directly related to their owner's wealth, humanity, and economic self-interest. Theories as to what constituted adequate housing, clothing, and diet for slave labor were almost as numerous as planters themselves. The dwellings that remain today at Horton Grove represent the best in a broad spectrum that ranged from shabby hovels with dirt floors and leaky roofs to the sweltering attics and musty basements of the "big house." Paul Cameron's major concern in regard to slave housing was that it provide a disease-free environment for his workforce, thereby reducing the expense of slave illness. The quarters at Horton Grove, which were constructed by slave craftsmen in the early 1850s, were the culmination of decades of gradual improvements aimed primarily at increasing labor efficiency.

Religion in itself was central to slave culture. Some plantation owners, such as the Collinses and Camerons, built chapels for their bondsmen and -women and brought in white missionaries to preach. The slaveholders' concern for the spiritual well-being of their black "family," however, tended to manifest itself in an emphasis on the authoritarian and paternalistic aspects of Christianity. Infused by a vibrant spiritual heritage and vitalized by more radical Christian tenets, such as the brotherhood of man, African American slaves developed their own brand of religion.

Farm Life

Children were an important part of the rural workforce.

The majority of nineteenth-century North Carolinians knew neither the ostentatious gentility of the white-columned veranda nor the vivid counterculture of the "quarters" stoop. The population of the state was comprised largely of ordinary farmers, not planters and slaves. Whether white yeoman or free black, landowner or agricultural laborer, most Tar Heels lived on small farms, over two-thirds of which in 1860 were composed of a hundred acres or less. Despite the pervading influence of the plantation, rural society was built around this broad middle class.

Typical of that class were Benjamin and Serena Aycock, who established a prosperous farm near the town of Fremont in Wayne County. In the 1840s, the couple moved into the then-new farmhouse that still stands on the property. In that dwelling, in 1859, the future governor Charles B. Aycock (known as the education governor) was born, the youngest of ten children. By 1870, with more than 1,000 acres, Benjamin Aycock was the seventh-wealthiest householder in the township.

Although awareness of social gradations permeated the antebellum South, the economic hierarchy, at least for white Carolinians, was only loosely fixed. Examples of "rags to riches" success were rare, but it was not uncommon for a family, over several generations, to improve its standard of living and thereby its social status. If prosperity often seemed less a function of skill and energy than of opportunity, inclination, and luck, the possibility of achievement stimulated personal aspirations and industry. A day laborer could strive toward renting a plot of land to work for himself, while a tenant farmer and his wife might dream of purchasing a small farm of their own.

James and Nancy Bennett were one such couple whose determination and effort were rewarded. In their early forties, after years of toil, the Bennetts succeeded in purchasing a modest farm in what is now Durham County with some $400 of borrowed capital. Though in a real sense a monument to the perseverance and good fortune of this enterprising rural family, the Bennett Place State Historic Site stands today as a memorial to a momentous event over which the Bennetts ironically had no control. Because of its convenient location on the old road between Raleigh and Hillsborough, which linked the final position of the Confederate army under Joseph E. Johnston to that of the Union army led by William T. Sherman at the close of the Civil War, the farm was chosen as the site at which to negotiate the terms for Johnston's surrender.

The Bennetts seemed satisfied with their lot. They might well have fared better economically had they attempted to maximize their profits by concentrating entirely on the production of marketable staples, but such a course of action involved inherent risks. As landowners, the Bennetts were not forced to place themselves at the mercy of the market merely to pay their rent. And unlike larger planters, they simply did not have the capital to invest in more fertile land, technologically advanced implements and machinery, or improved agricultural techniques that could increase efficiency and thereby lower production costs. The substantial debt incurred by the purchase of a deeper plow or the stronger mule necessary to pull it would have jeopardized their hold on the farm itself. Thus the Bennetts, and thousands of Carolina yeoman farmers like them, made do with what they had--employing the methods of their parents before them, basking in the warmth and love of their family and friends, and reveling in the independence and security afforded by working their own land.

Community Life: Country Stores and Gristmills

Conservative and self-sufficient as they may have been, nineteenth-century farm families like the Bennetts did not live their lives in isolation. Few weeks passed without the distraction of a trip to the local store, the stimulation of an enthusiastic religious gathering, or the conviviality of a neighborhood quilting bee. A strong sense of community pervaded rural life, buttressed by a tradition of social responsibility and communal interdependence.

Commercial centers such as the country store and nearby gristmill offered antebellum farmers more than essential goods and services. They provided a nucleus for community life. There rural Carolinians, whether planter or tenant, free black or white, converged to purchase supplies, grind their corn, or simply visit with neighbors and friends.

Gristmills also provided an essential economic service for the rural community. Milling was necessary not only to transform corn into meal and wheat into flour for human consumption, but also to reduce the cost of transporting these bulky agricultural commodities to market. The yield of an entire acre of corn could be reduced to around five barrels of meal, while a barrel of flour contained approximately five bushels of threshed wheat. In addition to decreasing the problems of transport, processed farm products generally brought a higher market price. It often paid southern planters or merchants who handled large quantities of staple crops to construct a gristmill, a cotton gin, or even a tobacco factory for their own use and that of the neighboring community.

Public Education

Debate over the establishment of a system of public education in North Carolina raged throughout the antebellum period. The issue involved more than determining whether the family, the church, or the state should assume the primary responsibility for educating society's youth. It was inevitably linked to larger questions concerning the necessity of formal education and the proper role of government itself. Finally, in 1839, the legislature passed a bill calling for the development of a statewide school system supported by county taxes and appropriations from the "Literary Fund," which had been created for that purpose over a decade earlier. But, because of public apathy and inadequate direction, public education was not firmly established in North Carolina until the 1850s, and even then not in every county and only for whites.

Religion in 19th Century Life

Religion too was a vital part of nineteenth-century American life. Though only about half of the free adults in North Carolina were members of an organized church, religious ideology, custom, and practice shaped the state's culture; and the local congregation, regardless of its denominational affiliation, formed the very core of the rural community.

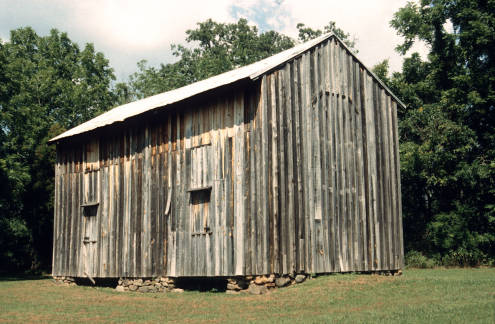

Church buildings in the rural South were generally constructed by congregations themselves. One member of a congregation donated a small tract of land and others the building materials and furnishings. All shared in the labor and took pride in the structure that they created. A simple cabin served many a congregation until they could enlarge or replace it with a frame meetinghouse. Some were eventually able to erect a more substantial structure of stone or brick.

Church services were more than an occasion to renew religious commitment; they were also a social event. Rural Carolinians gathered on the church grounds well before the meeting was to begin and lingered there long after the minister had departed. Many visited the graveyard, where one or more loved ones were buried, while others earnestly discussed the day's sermon. Yet invariably the topic of conversation turned to more temporal matters, such as the outcome of a forthcoming horse race or the current price of tobacco.

For many North Carolinians, however, the most exciting and important annual social occasion was principally a religious event. Since the Great Revival at the beginning of the nineteenth century, churchgoers gathered during the late summer in the rural South and Midwest for several days of services and celebration known as "camp meetings." Intended to renew the zeal of believers and to gain new converts, many such convocations attracted several hundred to several thousand participants. They offered an inviting opportunity to interact with old friends and fellow Christians as well as a welcome respite from normal routine.

By 1830 the Methodist churches that composed the Lincoln Circuit in the western Piedmont had designated a wooded tract near Rock Spring in Lincoln County as the permanent site of their yearly camp meeting. Though the families who gathered there each August held their services in the open air, within a few years a large rectangular "arbor" was built to protect the assembly from the blazing midday sun and the frequent summer showers. Constructed of handhewn timbers, the open shelter remains on its original site shaded by a grove of sturdy oaks. A pine pulpit on the low platform at the west end of the historic structure stands silent watch over the rows of empty wooden pews. Ordinarily, with the exception of the shrill calls of the resident bird population or the gentle rustling of the trees in the wind, all is quiet.

A series of crude single-story row houses, known as "tents," surrounds the central structure, forming a broad square. As their name suggests, these shedlike dwellings, built as temporary quarters for individual families during the annual meetings, gradually replaced the less permanent shelters employed by the earlier participants. Each consists of one or two rooms and a loft, the walls are unfinished and unadorned, and the floors are hard clay covered with sawdust or straw. Nineteenth-century worshipers, caught up in the fervor and the fellowship of a vital religious experience were little concerned with material comfort. And the same is true today when Rock Springs Campground once again springs to life in late summer.

Although camp meetings were a popular recreational outlet for rural and urban Carolinians alike, for the most part, they retained their basic religious character. And, when it came time to return to the problems and prospects of everyday life, laymen and clergy alike did so with the vivid memory of their involvement in a moving communal experience, a deeper commitment to their Christian beliefs, and a renewed awareness of their own self-worth.