See also: The Way We Lived in North Carolina: Introduction; Part I: Natives and Newcomers, North Carolina before 1770; Part II: An Independent People, North Carolina, 1770-1820; Part III: Close to the Land, North Carolina, 1820-1870; Part IV: The Quest for Progress, North Carolina 1870-1920; Part V: Express Lanes and Country Roads, North Carolina 1920-2001

Throughout the nineteenth-century, North Carolina was economically, socially, and politically a rural state. At midcentury no more than 2.5 percent of the population could be considered urban, and only the port city of Wilmington claimed as many as 5,000 inhabitants. Yet, while "progressive" Carolinians bemoaned the state's lack of business centers to compare with Richmond or Charleston, the process of urbanization, so apparent today, was clearly if gradually under way. The population of Raleigh doubled during the decade following the completion of the Raleigh and Gaston Railroad in 1840. The location and layout of Raleigh, established as the state capital in 1792, were carefully deliberated and planned. The present Capitol (1840) stands on the central of the original five squares delineated as open spaces in the city grid. And some twenty-five commercial and judicial centers throughout the state, such as Hendersonville, Salisbury, Warrenton, and Washington, were considered important enough in the federal census of 1860 to merit the appellation of "town."

The primary factor stimulating the growth of towns was trade. Consequently most were located at points convenient to water or overland transport. New Bern, the state's second-largest city, was situated near the mouth of the Neuse and served as a principal market for the region drained by the river and its tributaries. Fayetteville, on the other hand, was located near the fall line of the Cape Fear River and gained its prominence as a mercantile link between the coast and the Piedmont.

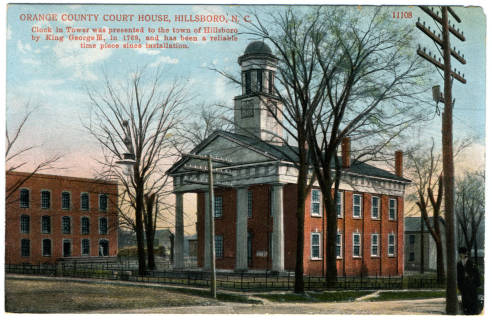

The courthouse occupied a prominent site in almost every county seat: on the main square or at the head of the one street that comprised the commercial district. Shops of local craftsmen were interspersed with stores of various sizes and shapes. Lawyers' offices, and the offices of a doctor or two, might well be found near the courthouse or scattered among the substantial residences that stood along the opposite end of the main street. In larger communities a bank was certain to dominate at least one corner of the busiest intersection, while a hotel, which was filled to overflowing during every "court week," stood on another.

County Government

Ordinarily centerpieces of antebellum towns, courthouses in North Carolina ranged from dilapidated wooden structures with decaying walls and crumbling chimneys to impressive monumental edifices of stone or brick. In the newly formed counties of the mountain region, a convenient tavern or converted barn might well serve to house the quarterly sessions of the county court until a suitable structure could be erected at the county seat. Farther east one was likely to find larger, more substantial court buildings, often with an adjacent clerk's office and jail, which embodied the aura of permanence and stability that local authorities wished to project.

Presiding over the county court were three to five justices of the peace. Commissioned by the governor on the recommendation of the local delegation to the state Assembly, the justices of the peace were invariably selected from the county's economic and political elite. Customarily addressed as "Squire," the justices served for life or as long as they maintained their local residence.

Four times a year the local justices gathered in Yanceyville to convene the county court. With power to summon grand and petit juries, the court had the authority to decide major civil actions and all criminal cases not punishable by death or dismemberment. However, because it was a common practice for the county court to deal exclusively with administrative matters during two of its quarterly sessions, it often took months for even the simplest case to come to trial.

Commercial Activity

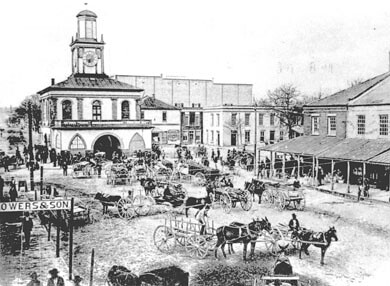

Nowhere was the importance of the market and its attendant commerce more clearly evident than in Fayetteville. Well before the city's incorporation in the late eighteenth century, enterprising Scottish merchants had made it a prominent center of inland trade. Here the antebellum farmer or country storekeeper had no need to halt his overloaded wagon in order to ask for directions when he arrived. The Market House, constructed in 1838 at the intersection of the four major thoroughfares leading into Fayetteville, was the focal point of the town, in which the buildings of its Liberty Row reflect two centuries of change. The Market House site was also the location for the sale of enslaved people.

The splendid two-story Market House is a brick structure of Georgian design and a classic blend of form and function. The ground level is an open arcade that served as the center of daily market activity. Stalls were set up in and around the building, while wagons filled with produce jammed the broad intersection. Yet Fayetteville's Market House was more than the nucleus of local commerce. The town hall on the second floor provided a seat for municipal government and a focus for community life and culture. On a given afternoon or evening, though the market might be quiet, the building was still likely to be crowded with people attracted by a meeting of the town commission or a lyceum lecture. Even those who seldom had business there could not easily escape the impressive structure's subtle influence.

Almost every night, particularly in the fall, the roadsides leading into Fayetteville and other substantial commercial centers were dotted with the campfires of those eager to be on hand when the trading started early the next morning. At sunrise the market came alive as teamsters jockeyed to get their wagons into the best positions and farm boys vied with merchants' apprentices setting up their inviting displays. The air was filled with the sounds of crowing roosters, barking canines, and shrill human voices already beginning to hawk their wares. And the pleasing sight of snow-white cotton, bright red apples, and golden ears of corn joined the rich smell of hay and manure as morning melded into day.

The town market, however, was by no means the sole location of commercial activity in antebellum cities. Stores and shops lined the principal streets near the market hall and around the courthouse square. Typically such retail outlets offered a broader selection of merchandise in terms of quality and sold items in smaller quantities than could be purchased wholesale at the central market. While country storekeepers attempted to carry a complete range of products, their urban counterparts were becoming increasingly specialized, with dry goods shops, groceries, apothecaries, and hardware stores all competing for the business of town dweller and rural visitor alike.

Urban areas were a magnet for craftsmen as well. In addition to the blacksmiths and millers found in the countryside, almost every town could count carpenters, coopers, harness makers, cobblers, and tailors among the ranks of its mercantile community. Usually the services of at least one butcher, baker, printer, gunsmith, jeweler, milliner, and barber were available too.

One of the state's best known and most competent craftsmen was a free black cabinetmaker named Thomas Day. Born in Virginia, he moved during the 1820s to Milton in Caswell County, which was rapidly becoming the center of the northern Piedmont's prosperous tobacco economy. Though he began his furniture-making business in a modest way, most likely on his parents' farm outside of town, within a few years he had established a thriving shop on Milton's main street. By midcentury, Day had purchased the Union Tavern, once the largest and finest in the area, and converted the handsome two-story brick structure into a commodious residence, convenient showroom, and functional workshop.

Society and Culture

The elegant town houses of planter and merchant alike reflected their desire to be as much a part of the flourishing social life of the urban community as of its economic enterprise. Among antebellum urban buildings reflecting the life and enterprise of the merchant-planter class that can still be seen today are the Joseph Bonner House (Bath, Beaufort County), the Zebulon Latimer House (Wilmington, New Hanover County), the Maxwell Chambers House (Salisbury, Rowan County), the Roberts-Vaughn House (Murfreesboro, Hertford County), the John Vogler House (Winston-Salem, Forsyth County), Liberty Hall (Kenansville, Duplin County), and the Oval Ballroom (Heritage Square historic buildings, Fayetteville, Cumberland County). Churches also displayed the prosperity of antebellum Tar Heel towns. Among significant structures still standing are Christ Episcopal Church in Raleigh, Purvis Chapel in Beaufort (built by the Methodist Church in 1820 and now an AME Zion church), and the First Presbyterian Church in Fayetteville. Fraternal Lodges--such as the Columbus Lodge (1838) in Pittsboro, in Chatham County, and the Eagle Lodge (1828) in Hillsborough, in Orange County--were also a part of the urban architectural milieu.

One of the best and most widely known female academies in antebellum North Carolina was the Burwell School, located in the thriving court town of Hillsborough, in Orange County. The quality of the school's direction, along with its commitment "to cultivate in the highest degree [the] moral and intellectual powers" of its students, attracted scholars from as far away as Florida and Alabama, and secured the patronage of some of the most prominent families within North Carolina. In accordance with accepted legal practice and social custom, the owner as well as the titular head of this remarkable institution was a male, the Reverend Robert A. Burwell; but, in fact, the school was originally conceived, painstakingly organized, and meticulously managed by his energetic and capable wife, Margaret Anna.

The formative influence of Burwell School and other private academies was significantly enhanced by the urban cultural milieu. Literary clubs and debating societies were in vogue.

The dramatic productions of the Thalian Association in Wilmington compared favorably with the "professional legitimate drama" that flourished in Richmond, Charleston, and New Orleans. Founded in 1788, the association's annual repertoire ranged from Shakespearean tragedy to contemporary comedy.