See also: Camp Meetings; Mourner's Bench; Revivals.

The Great Awakening was one of the earliest Protestant revival movements to sweep through North Carolina. This religious revival, which actually encompassed two parts separated by a few decades, established several new sects of Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians in North Carolina in the 1700s and 1800s. The First Great Awakening occurred in the 1730s. After that, the American Revolution effectively halted all religious movements in North Carolina. Religious revivals returned to the state around 1800 with the Second Great Awakening. This movement lasted up until the outbreak of the Civil War.

In the 1730s Methodist missionaries, reformers who had split with the Church of England, came to the American colonies to preach a new way of worship. These missionaries emphasized a personal participation in religion and a new connection to God that allowed freer, more passionate and enthusiastic religious practices. These evangelical expressions differed dramatically from Anglican methods of worship, which often followed dispassionate rituals.

George Whitefield, one of the most famous of the Methodist missionaries, traveled through North Carolina in 1739 and returned to the colony again in 1765. On his 1739 trip he passed through Edenton and stopped at Bath on 22 December before moving farther south through New Bern and into the Cape Fear River region. Whitefield had no success converting North Carolinians, and he quickly moved on to South Carolina to continue his work. Almost 30 years passed before another Methodist minister made an effort to convert the people of North Carolina. Devereux Jarratt, a powerful and convincing speaker, worked in North Carolina from 1763 until 1775, warning listeners to recognize their sin and counseling them that the only remedy for their weaknesses was to rely on Christ for salvation. One of Jarratt's lessons was that the convert needed to develop a personal connection with God. This idea, which Whitefield had taught earlier, became very important to later revival movements.

Baptist Shubal Stearns of Connecticut, a follower of Whitefield and a former Congregationalist, arrived in Orange County in 1754 and established the influential Sandy Creek Baptist Association in 1758. When Stearns died in 1771, the Baptist church lost one of its most important leaders. Baptists were slow to be swept up in the revival movement, and not until after the Revolutionary War did Baptists regain strength in North Carolina.

David Caldwell was a Presbyterian missionary who came to North Carolina in 1765, opening a school to train other ministers. One of his students, James McGready, came to Guilford County in 1778 and later worked as a minister in the Haw River and Stoney Creek congregations. His message attacked the immorality and greed he saw in many Piedmont settlers. In Guilford County, McGready trained several Presbyterian ministers.

McGready and a group of his students traveled to Kentucky, where, in 1800, they organized the first Great Revival, signaling the beginning of the Second Great Awakening. Among the organizers was William McGhee, a Presbyterian, and his brother John, a Methodist. When participants returned to their home churches, the excitement generated by the revivals spread to the other churches. One of those in the crowd listening to McGready and other speakers was Lemuel Burkitt, the pastor at the Sandy Run Baptist Church in Bertie County and an active participant in the Kehukee Association of eastern North Carolina Baptists. His reports to congregations so inspired the Baptists that they began to hold their own revivals. In 1802 and 1803, Baptist revivals drew large crowds. In late March 1802 a Mecklenburg County revival attracted 5,000 people who heard 17 preachers urgently deliver their salvation message. By 1803, the Baptists had gained 1,500 new members. Spreading like a fire, the revival movement swept through the Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist faiths throughout the South.

Presbyterian revivals and camp meetings were held at the Cross Roads Church and Hawfields in Orange County. In January 1802, David Caldwell called for a meeting at Bell's Meeting House on the Deep River in Randolph County. He invited all area denominations to the gathering. From that one meeting, waves of revivals spread out across the state. In June 1802 thousands attended a revival at the Rutherford County Courthouse.

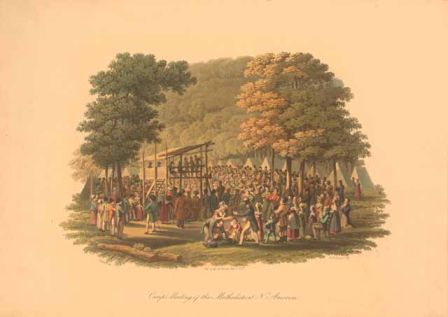

The religious fervor continued when the Methodists began to hold revivals at their camp meetings. In 1805 a camp meeting was held at Bethel, where 300 people were converted. Nearby Rock Spring became the location for one of the state's largest religious meetings.

The Second Great Awakening peaked in 1804, but aspects of it continued until the Civil War. After the end of the War of 1812, revivals were often held in cities-including Raleigh, Tarboro, and Fayetteville-rather than the countryside. The Raleigh Star reported in 1829 that "a considerable revival has taken place in the Methodist Church in this town, within the last ten days. . . . The preachers and leading members exert themselves in a surprising degree." Later, Greensboro and Charlotte also experienced religious revivals rooted in the Second Great Awakening.