2023 estimated population = 482,295 (United States Census Bureau)

Less than 250 years ago, the bustling capital of North Carolina was nothing more than a forest of oak and hickory trees located near the Wake Cross Roads and the tavern of early entrepreneur Isaac Hunter. The seat of government was a hotly-debated issue in the early days of North Carolina with well-established cities vying for the honor of being named capital. So how was it that the capital was born from a wilderness and not an already-existing city?

During the colonial period, North Carolina's legislature was reluctant to designate a fixed seat of government. As a result, legislative sessions were held in various locations throughout the state which required a great deal of travel on the part of the legislators. Numerous attempts were made to establish a capital, but none proved successful. Perhaps the most memorable attempt was put forth by Colonial Governor Arthur Dobbs. In 1758, the North Carolina legislature approved an act to purchase Dobbs' 850-acre plantation (located in what is now northeastern Lenoir County) to establish “George City” in honor of King George II. However, the British government did not approve the legislation and the city was never established.

Starting in 1766, New Bern served as the colony's seat of government, and Tryon Palace was constructed to serve as the Governor's residence. During the Revolution, however, the Palace was too much associated with royal government. Wary of invasion, the state government once again became migratory. In the years between 1715 and 1787, the legislature met at numerous locations throughout North Carolina including Queen Anne’s Creek, Edenton, Wilmington, Bath, New Bern, Kinston, Halifax, Smithfield, Hillsboro, Salem, Fayetteville, and Tarboro.

In 1787, the North Carolina legislature voted that the Constitutional Convention (appointed to discuss the new federal constitution) should decide on the location of North Carolina's state capital. The Constitutional Convention resolved that the capital be within ten miles of Isaac Hunter's tavern in Wake County, and that the State Legislature was responsible for choosing the exact site. No further action was taken on this issue during the sessions from 1788 to 1791, because of opposition from those who claimed Wake County was "the wilderness" and could never develop into a city. In early 1792, advocates of the Wake County site finally garnered enough support within the General Assembly to establish a commission to identify land for the new city. The Assembly appointed another group to oversee the building of a state house for the new capital.

The commissioners gathered at Isaac Hunter's residence in March of 1792, but soon adjourned to the nearby home of State Senator Joel Lane. About ten days later they voted to purchase 1,000 acres of Lane's plantation for £1,378 to serve as the site for the new capital.

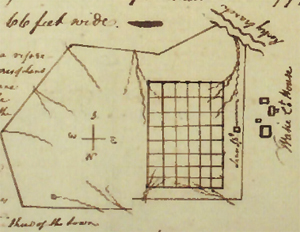

William Christmas, another senator and a surveyor by profession, drew the plan for Raleigh. Using a total of 400 acres, Christmas designated the axial center of the city as Union Square. It was composed of six acres and intended as the site of the future State House. The map described the square as "a beautiful eminence which commands a view of the town and fine prospect of the surrounding county." Flanking the corners of the center square were to be four four-acre squares or parks reserved for public purposes. These were named Caswell, Nash, Burke (for the state's first governors) and Moore (in honor of Attorney General Alfred E. Moore). The four main streets were named Halifax, New Bern, Fayetteville, and Hillsborough, judicial districts toward the north, east, south, and west. These streets ran from the four sides of Union Square; the other 17 streets were named for the remaining judicial districts, the points of the compass, the commissioners themselves, and several other prominent citizens, including the former owner of the land. The remaining 276 acres were marked off in one-acre lots to be sold at public auction, with the proceeds used to build the capitol and other public buildings.

The name for the new capital was suggested by Governor Alexander Martin in honor of Sir Walter Raleigh, who was responsible for sending the first colonists to North Carolina.

Raleigh's initial development was slow. One factor which contributed to delayed growth was the occurrence of many fires in the early 19th century, including a fire that burned down the statehouse in 1831. The new State Capitol building was completed in 1840 around the same time that the railroad was established. Raleigh's city limits expanded for the first time in 1857.

The Civil War delayed further development in Raleigh as it was affected by the ravages of war. However, the establishment of several learning institutions before and after the Civil War assisted with its growth in the early part of the twentieth century. These institutions include Peace College (1857), Shaw University (1865), Meredith College (1891) and North Carolina State University (1887).

Raleigh flourished during the First and Second World Wars and thereafter. As the center of North Carolina government and with the addition of the nearby Research Triangle Park (1959) Raleigh has brought an influx of people and businesses to the state. In 2009 the estimated population was more than eight times what it was in 1940.

Today Raleigh is home to many cultural and historical sites including the publicly funded North Carolina Museum of History, North Carolina Museum of Art, and the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Raleigh has many theatre and musical groups including the North Carolina Symphony. Raleigh is home to the 2005 – 2006 Stanley Cup Champions, the Carolina Hurricanes (National Hockey League).

Raleigh history digital collection