Part i: Introduction; Part ii: 18th Century to Antebellum Era; Part iii: The Civil War & Postwar Era; Part iv: 1880s to 1920s; Part v: The Great Depression; Part vi: 20th Century and 1970s Revival; Part vii: 21st Century and Beyond

Whole Cloth

Whole-cloth quilting, which allowed seamstresses to show off their skills by stitching complex patterns on a solid quilt top, saw considerable popularity on both sides of the Atlantic during the eighteenth century. One example is the cream silk crib quilt that an unknown maker stitched for John Todd Cocke Wiatt’s 1781 christening. Though likely made in Virginia, the diminutive bedcovering came with Wiatt to Raleigh where he later became a Wake County militia commander and the first marshal of the state Supreme Court. The piece is complexly quilted with floral and geometric designs.

Chintz Appliqué

The first widespread quilting tradition to take root in North Carolina was chintz appliqué or broderie perse (French for “Persian embroidery”). The trend drew upon English quilting traditions and became popular in the mid-Atlantic and southeastern United States during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Like whole-cloth quilting, this style was a marker of status, and women made chintz appliqué quilts to showcase their fine needlework skills and abundant free time rather than just to keep warm. Using colorful printed chintz imported from Europe, makers cut out figures from the fabric and arranged them into new patterns and scenes on a white or cream ground cloth. Such quilts tended to be large, thinly batted, and intricately quilted. Common motifs included birds, fruit, and flowers. Large, vinelike “trees of life,” also called palampores after a style of printed Indian cloth, featured prominently in many of these bedcoverings. Elizabeth Heritage Cobb of Lenoir County made a center-medallion style quilt featuring roosters perched upon a branching tree of life for her granddaughter Susan Cobb ca. 1803–1820. Pieced pinwheels and four outer borders surround the central motif. The exquisitely quilted, thinly batted bedcovering stretches nearly eight feet square.

A few years later, Rosannah McCullough, who was likely from Lincoln County, created a chintz appliqué quilt featuring a central fruit basket surrounded by floral clusters and stylized pheasants. She stitched her name and the date “1832” alongside the central design, ensuring that viewers would associate the bedcovering’s fine sewing with its maker. Elite women learned sewing skills at an early age, creating samplers under the supervision of female relatives or needlework teachers at female academies. Similarly, they learned quilting styles and patterns from their social networks of family members and friends. As they reached their adolescent years, young women tackled more complicated projects and began creating household textiles for their bridal trousseaux. Rosannah McCullough may have created her quilt in preparation for her debut or wedding, or she may have made it as an expression of her personal aesthetic. Chintz appliqué quilts—especially those with a center medallion format like Cobb’s and McCullough’s—remained popular among North Carolina’s upper class until the 1840s.

Stuffed Work

Another style which upper-class Tar Heel seamstresses embraced in the early–mid nineteenth century was stuffed- or corded-work—also frequently called trapunto or whitework. Stuffed-work projects involved stitching elaborate floral and geometric outlines through two layers of fabric—a quilt top (often white whole cloth) and a loosely woven backing. Makers would then separate the individual fibers of the backing fabric to create tiny holes through which to insert cotton batting. A three-dimensional effect resulted with the “stuffed” areas creating detailed raised motifs upon a relatively flat background. Stuffed work could be used in concert with other styles such as chintz appliqué or alone on a whole-cloth ground. In Burke County, a member of the Tate family meticulously stitched and then stuffed swags, grapevines, and leaves around a central flower-basket motif in a ca. 1840–1860 whitework bedcovering.

Though fancy quilting fell within the social sphere of elite, white women, others did participate actively in the craft. Highly skilled enslaved women devoted countless hours of labor to many of the early decorative quilts now associated with or attributed to prominent white North Carolina families. Enslaved workers on Cool Springs Plantation in Edgecombe County helped create a lavish trapunto quilt in 1850. The piece, which descended in the Pittman family, features intricately stitched and stuffed vines, flowers, and grape leaf clusters.

Appliqué

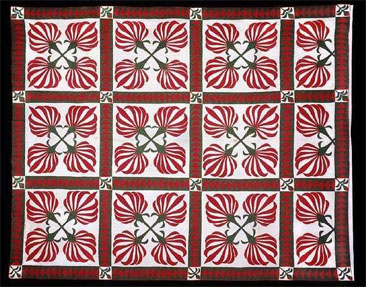

Concurrent to whitework, appliqué quilting also took off in antebellum North Carolina. Unlike the famous

Baltimore Album quilts from the mid-Atlantic region, which featured multiple equal-size blocks with a variety of motifs, Tar Heel quilters tended to prefer repeating album-style quilts with numerous identical blocks. Appliqué quilting was not a make-do craft. The technique used fabric inefficiently, and the long hours it took to invisibly stitch a tulip petal to a quilt top was, for many Tar Heel women, better spent tending to farm chores. For those who had the time and fabric to devote to appliqué, red and green proved popular colors.

Mary Frances Donohue Johnston of Caswell County, like many North Carolina quilters, chose a floral motif separated by pieced sashing for her quilt. She exquisitely appliquéd a Cotton Boll pattern with nine whole and three half blocks in 1860. Appliquéd rosebuds grace the corner blocks of the red-on-green pieced-triangle sashing, and tiny quilting stitches outline the decorations. Around the same time Johnston made her quilt, members of the Moravian Boozer family created a Dutch Tulip pattern appliqué quilt in Forsyth County. Though the green fabric used for the foliage has faded to tan over the years, the delicately attached stems, leaves, and petals reveal the Boozer women’s impressive skill.

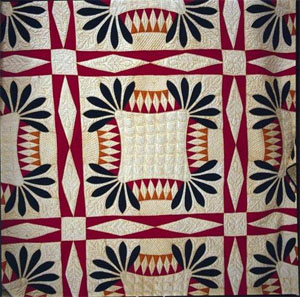

Early Pieced

Though not as popular as appliqué, North Carolina women did make pieced quilts during the antebellum period. Some broderie perse quilts include pieced elements or borders. Quilters occasionally pieced leftover chintz bits into fanciful patterns like the lone star quilt Mary Rhodes of Washington County made in 1825. Others created pieced quilts using the same colors and motifs popular in appliqué quilting. Though piecing tended to use less fabric than appliqué, creating curves and small details required greater skill. Louisa Green Furches Etchison pieced an elaborately detailed Whig’s Defeat quilt in preparation for her 1852 Davie County wedding. Clearly a perfectionist, Etchison kept the bedcovering in quilting frames for three months, during which time her fingers began to “fester” from the intense work. She would only accept assistance from her mother and sister Sarah, but then pulled out Sarah’s stitches after apparently

deeming them unsuitable. Louisa obviously set the bar high, as the piece is meticulously quilted with scallops and flowers at an unbelievable twenty-two stitches to the inch.

Despite the time and effort elite women like Etchison devoted to quiltmaking, most middling- and lower-class North Carolinians used blankets or coverlets as bedcoverings during the mid-nineteenth century. Fabric was expensive, and those who wove their own could more efficiently create an overshot coverlet than stitch a quilt. This began to change, however, when the state’s first mechanized weaving factories opened in the 1830s–1840s. Though the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 had invigorated the domestic textile industry, northern mills produced far more fabric than the few that operated in the South, and upper-class customers still relied on European imports for finer fabrics and prints.

In 1837, Edwin Holt opened a cotton mill in what is now Alamance County. He soon began producing the first dyed fabric in the South and also developed North Carolina’s first manufactured patterned fabric, known as Alamance Plaid. The close proximity of manufactured cloth allowed some rural consumers who had previously woven their own fabric to begin purchasing it. Enterprising women pieced scraps leftover from making clothing into quilts. Edith Anne Williams Uzzell of Wayne County used brown and blue plaids to make a pieced checkerboard pattern quilt. Though it is impossible to be certain whether Uzzell’s plaids came from Holt’s Alamance factory, the distinctive colors used and the quilt’s circa 1850–1860 date make an association quite possible.