Part i: Introduction; Part ii: 18th Century - Antebellum; Part iii: The Civil War & Postwar Era; Part iv: 1880s to 1920s; Part v: The Great Depression; Part vi: 20th Century and 1970s Revival; Part vii: 21st Century and Beyond

Pieced Quilting to 1970

Piecing remained the technique of choice for most twentieth-century North Carolina quilters. The method allowed makers to conserve fabric, and the wide availability of patterns permitted a great number of options. In some circles, the craft declined as families left their rural roots to work in the tobacco and textile mills or World War II–era industries. As people moved to towns and cities and started shopping for their bedcoverings and home furnishings in department stores, some began to view quilting as old-fashioned. Still many North Carolina women continued to make quilts for warmth, beauty, and symbolic functions.

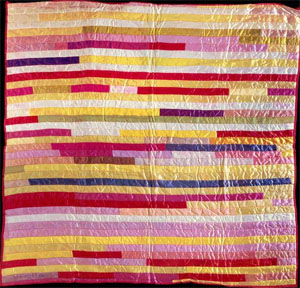

A new style that emerged in North Carolina and neighboring states during this time period was the funeral ribbon quilt. The growth of the undertaking business and the allied florist trade during the twentieth century resulted in an increasing emphasis on sending flowers to funerals. Prominent individuals could receive dozens if not hundreds of arrangements. Resourceful seamstresses, used to wasting nothing, began removing the colorful acetate florist ribbons and piecing them into quilts. Such a quilt would always be associated with the deceased person, and its size would attest to the number of bouquets of flowers sent and thus the concern and care expressed for the family members during their time of grief. When Margaret Irene Wicker died in Lee County in 1958, an unknown quilter used the red, pink, yellow, and white ribbons from the flowers sent to her funeral to make a strip quilt.

Others, like Elizabeth Lee Graham Jacobs, who lived in Columbus County’s Waccamaw-Siouan community, made quilts to mark life’s happier milestones. She gave many quilts away to friends and family and to benefit tribal charities. She crafted a Diamond Star Variation quilt from feed-sack and scrap cloth and gave it to her daughter as a wedding present in 1963.

Quilting Revival

During the 1970s, North Carolinians and other Americans grew interested in the quilting traditions of their forebears. Preparations for the 1976 National Bicentennial focused on historic craft activities, and many looked at their mothers’ and grandmothers’ quilts with renewed appreciation. Gladys Baker of Wake County prepared for the national birthday by coordinating projects such as the “Historical Landmarks of Wake County” quilt. Baker directed a group of seventeen women in creating thirty appliqué images from the county’s past including tobacco barns, old churches, and popular agricultural products. The finished quilt, constructed in patriotic red, white, and blue polyester blend, traveled to multiple locations and received praise in the press.

Cary resident Jane Long also took up quilting during this era. She created a historically inspired “hands all around” pattern bedcovering in 1983, which she exquisitely hand quilted in a crosshatch and swag pattern. The piece won several competitions and was featured in a national quilting magazine. Though she drew upon traditional techniques, the popular 1980s-style fabrics she used and the way in which she learned to quilt—as an adult from fellow hobbyists—speak to the trends of the quilting revival era.