Part i: Introduction; Part ii: 18th Century to Antebellum Era; Part iii: The Civil War & Postwar Era; Part iv: 1880s to 1920s; Part v: The Great Depression; Part vi: 20th Century and 1970s Revival; Part vii: 21st Century and Beyond

Quilting and the Civil War

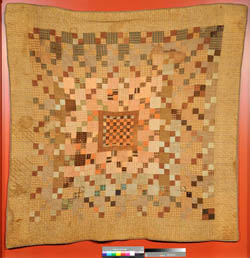

The advent of the Civil War brought changes to North Carolina’s quilting traditions just as it did to all aspects of life in the Tar Heel state. Federal blockades and rampant inflation limited access to imported cloth, and local mills shifted to producing fabric for the war effort. Some women turned to home spinning and weaving in order to provide cloth for their families. Naturally, decorative quilting took a backseat to more pressing needs. And some—like members of the Ramseur family, who hid a cherished chintz appliqué quilt in the rafters of their Lincoln County home—did seek to protect prized quilts from foragers wearing both blue and grey. For others, the war’s impact influenced the types of quilts they made. Ann Sloan Lowrie Knox of Mecklenburg County sent five of her six sons to fight for the Confederacy. In 1864, two sons were killed in battle. Another died of disease the following year. A fourth perished from lingering wounds shortly after Confederate surrender. To commemorate her family’s overwhelming loss, Knox created a plaid checkerboard medallion quilt using fabric scraps from her deceased sons’ clothing.

Post War Quilting

In the decades following the war, quiltmaking in North Carolina expanded and democratized. Formerly enslaved North Carolinians—one third of the state’s population—were now free and could use and pass down the quilts they made within their own families. The state’s textile industry blossomed and locally produced fabrics became more widely available and affordable than ever before. With the invention of synthetic aniline dyes, new colors debuted, and cheaper fabric printing technologies allowed consumers access to a wider variety of choices. As more families were able to buy fabric and thus had more leftover bits and remnants, they started to piece quilts. The scrap quilt was born.

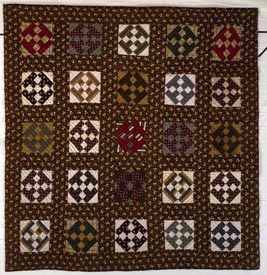

In 1879, ten-year-old Mary Herring of Sampson County made a Double-T pattern quilt using spare cloth from sewing clothing. She hand-pieced all of the maroon, brown, and tan printed fabric and quilted the piece at ten stitches to the inch. Girls like Herring learned to sew as children and often tackled complex projects by their early adolescent years. Still, for such a young girl making a full-size quilt, Herring’s craftsmanship was remarkable.

Patience White of Alamance County also used sewing scraps to piece together a log cabin quilt in 1907. White, who was born into slavery, made the bedcovering from over one hundred different fabrics, likely saved up for decades. Instead of quilting the bedcovering, she secured the batting with embroidery thread “ties.” Since it had been illegal to teach enslaved people to read and write, White was illiterate until late in her life. She clearly resolved to get an education, however, as she finally learned to read and write in her seventies. She gave her log cabin quilt to her teacher as a gift of gratitude.

Though utilitarian quilting became much more prevalent in the years following the Civil War, fancywork did not die out. Red-and-green repeating-pattern appliqué continued to be popular, yet the scale of the patterns changed over time. Julia Pearce made a tulip-and-plume reverse-appliqué quilt (a technique whereby appliquéd fabric is cut away strategically to reveal ground fabric underneath) circa 1880–1900 in Randolph County.

As in earlier examples, she used triple sashing and checkerboard corner blocks. However, her quilt features only four large repeating blocks rather nine or twelve smaller ones as had been common in previous decades. Colors like cheddar, teal, and claret became popular during this period. Ara Adner Williams of Wake County pieced an exquisite Heel Tap and Shoe Point quilt in cheddar, brown, and claret. She quilted the piece in exceptionally fine parallel lines.